|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

needy people. There were ten men and also two women who were - er - expected to look after the place for the others. In mediaeval England you could not be deserving if you were not a good Christian so that was a pre-requisite for a place at Browne’s. I am sure Mr Browne’s motives were mainly altruistic but I would be surprised if he did not also have an eye on a smoother passage through Purgatory and ending up on the right side of St Michael’s soul-weighing Scales of Doom! William. in fact, died as much as five years before the building was consecrated so I hope he already had enough credit in the Bank of Virtue. Each resident had a tiny “cell” within what is the main room today and was the dormitory in mediaeval times. To the east of this room was the chapel in which they were compelled to pray twice every day for the soul of the founder. That chapel is largely unchanged today and the subject of this article. The residents were also compelled to attend nearby All Saints Church on Sundays. The residents were clothed in a woollen uniform (which would have been unbearably hot in Summer) and fed, probably frugally. This was a considerable complex, with the dormitory occupying only the south side of a quadrangle rather in the style of a mediaeval monastery, Above the dormitory were the offices of the warden and confrater - a priest. To the east of the quadrangle were the warden’s living quarters. There was a cloister to the west and the square was completed by a range of service buildings including three kitchens, a hall and brew house. The latter was there, of course, not because the residents were expected to have a tipsy time but because mediaeval water was not safe to drink! There were also two small gardens. One must surmise that some of these building were to serve the warden and/or the Browne family. Being a private chapel - it is managed by a Trust to this day - it avoided the constant expansion and modernisation that afflicted so many parish churches and, in particular, it avoided the depredations of the modernising monsters of the Victorian age. The chapel is tiny and unspectacular but it still has six misericords and, most precious of all, a wonderful array of mediaeval stained glass. The glass itself is worth the visit here. William Browne’s arms are much in evidence. The mediaeval hospital is today a heritage attraction and the residents, of course, no longer occupy cells in a hall! The building is the frontage of a secluded close, the other side of which has a group of later buildings, replacing the original service block, which provide simple flats for single, non-pet-owning people who can live independently or with the aid of carers. They pay a modest weekly maintenance charge and are not regarded legally as tenants because they pay no rent. Services are still held weekly in the chapel but residents do not have to attend. I understand also that the women no longer have to skivvy for the men! Five hundred and fifty years and William Browne’s legacy lives on. I hope he literally found his reward in heaven. |

|

|

|

Left: The view through from the main door, through the hall to the chapel beyond the panelled wall. Right: The view towards the entrance. This is the room where the residents lived in cells, five to each side. The space allocation was not generous but it pays to remember that this lodging would be weatherproof, probably comparatively warm and the residents would not be sharing one room with their children and/or their livestock! |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

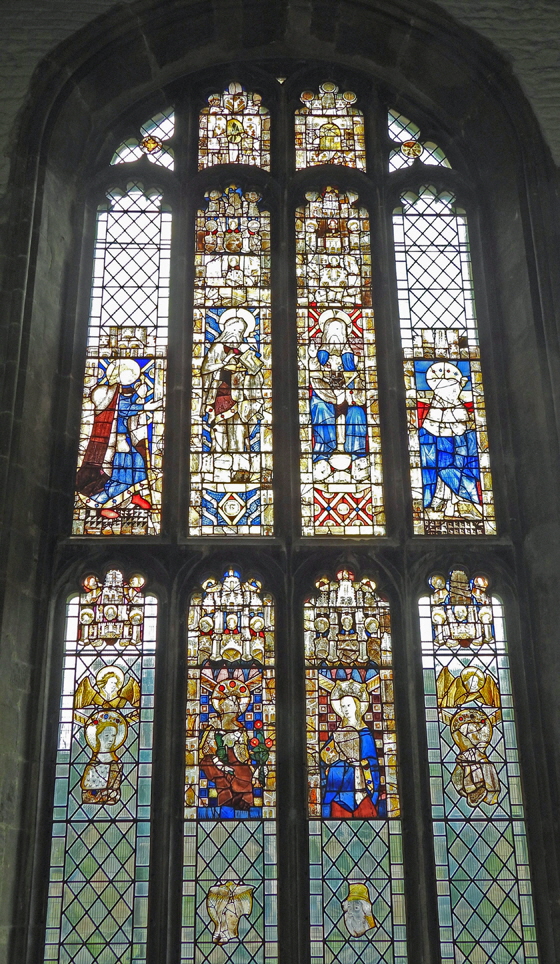

skin .Centre is the Trinity. God dominates. Around his midriff area in Christ crucified. Above Christ’s head is the Holy Dove. The right hand panel shows. a crowned royal saint, with Edward the Confessor and St Edmund the prime candidates. It is an obvious reconstruction. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: This panel is to the left of the three shown above. The pilgrim staff and hat mark this out as St James, whose shrine in Santiago de Compostella in northern Spain was - and still is - one of the most important pilgrim destinations in Europe. Centre: One of the two panels at the bottom of the south east window. Perhaps this is an OT prophet, although his cheery demeanour suggests someone more prosaic and contemporary. Right: The other panel has a female saint, probably Mary, her head adorned by an angel. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The lower part of the south east window. This is the lady’s space! Note the use of coloured “jewels” on the crowns. Left is, again, probably the Virgin with a demi-angel above her head. Second left could be Mary too, holding a garland of roses and lilies. Second Right: Also probably Mary, holding a three light Perpendicular style window, a symbol of the Conception, Right: Yes, this is probably Her too! |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

The top lights of the south east window. They very obviously have been reconstructed from fragments. Each has architectural features. In the centre light we can see embattled fortifications which could refer to the town’s Norman castle or its town wall, both long demolished. Most intriguing, perhaps, are the heads. Who were these people? |

|

|

||||||

|

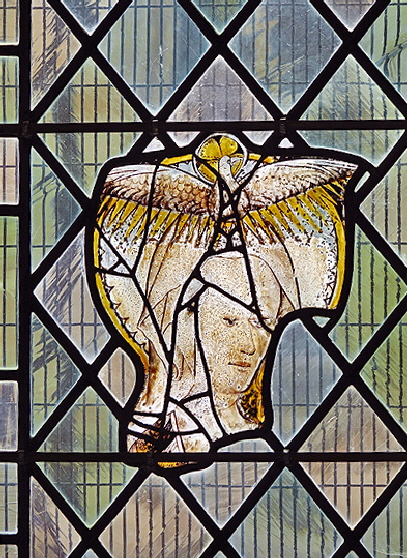

There are six misericords here. Left: Here we have the old misericord classic, the mermaid. In her right hand is the mandatory mirror. Sadly the comb in her other hand has been damaged. I must repeat here the received wisdom that the mermaid was seen as a symbol of the futility of lust. I am sure this must be true. But here at Browne’s Hospital and in many misericord ranges, lust is the only sin that needs to be portrayed, it seems. I have more than a suspicion that mediaeval carpenters had a convenient excuse to produce a carving that they thought was a bit of dirty fun! There is another story to be told here, however. The Hospital literature described this misericord thus: “Bearded man with rayed halo, arms outstretched to the height of head, left hand holding a disc, right hand missing. A bird’s wing covers the naked torso. On the right is also a body naked from the waist, covered by a wing”. Wh-a-a-a-t? The volunteer on duty expressed ignorance and so I showed him the picture on my digital camera. I guessed at why it was mis-described and was proved right. They had copied verbatim the descriptions from GL Remnant’s “Catalogue of Misericords of Great Britain” (1969).That is indeed the definitive work on the subject but Remnant got this wrong - very clearly. This is another example of what I call the “Pevsner Phenomenon”. So important and definitive were his books that nobody ever questioned them so his mistakes - inevitable in such a monumental body of work - are repeated by Church Guides (not to mention English Heritage’s listings) throughout the land and probably will be forever! I can only hope the curators at Browne’s amend their literature in due course. Right: (Photo: Bonnie Herrick) The only foliate decoration in this range. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: Of the remaining misericords, three seemingly represent eagles but this one has two rather companionable-looking lions. This is one of two seats that also have interesting “supporters” (that is, subsidiary carvings to left and right of the main designs), a feature unique to England. One is shown in detail below. Right: Two eagles back to back, wings intertwined. The eagle supporters carry speech scrolls. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A single eagle. Right: Two eagles addorsed (that is, back to back) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are area couple of nice poppy heads. Left: Two more eagles (!). Centre: Two dogs. Right: One of the lion misericord supporters. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The arm rests of the misericords are adorned with carved angels. Right: A strange aberration here. Just as the misericords are fairly restrained in their subject matter with the exception of the mermaid, there is this exception to the angel armrests and, perhaps not coincidentally, it occupies the far right position in the range of stalls with the mermaid misericord itself. It is almost as if the carpenter decided to have a little bit of fun at the extreme end of the stall range where the senior clergy would not be sitting. This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Where there are extensive misericord ranges within our cathedrals it is noticeable that the east facing stalls where the higher caste clergy disported themselves (as opposed to the much more numerous north and south facing stalls) often have misericords of more mannered nature; sometimes even images of the bishop himself. The more flamboyant stalls are generally on the north-south axis. Misericord carving is one of the great mysteries of mediaeval churches: just why were carpenters allowed to be so irreverent in the most sacred space of a church or abbey? The broad answer is that we have to accept that mediaeval Christians were far more liberal in their attitudes as to what happened at the margins of their religions than Christians seemingly are today. Stonemasons took advantage of this freedom too, as you will see throughout these pages. So too the producers of mediaeval psalters (books of psalms). The Rutland Psalter for example - housed at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire - has the most outrageous sexual and scatalogical imagery in its margins. It does seem on the face of it that the clergy were perfectly happy with this latitude, and probably themselves amused by the resultant fun. But it is likely that there were unwritten conventions, well-understood by the craftsmen, that kept things within boundaries. This carving is very hard to make out but the head of the creature seems to be at the top with perhaps three lips or two mouths. His ears are folded and the “wrong” way round. A long tail is curled around his body and he apparently has neither legs nor wings! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A saintly arm rest carving. Right: Detail of the mermaid misericord. She holds a mirror in her left hand but her comb in the right hand has been damaged. Interestingly, this mermaid has two bodies. Is it possible that this was to be two mermaids with the one on the left being consumed by a monstrous mouth, possibly the gates of hell? The comb and mirror are symbols of the mermaid’s vanity which reinforce her as a siren character enticing men into fruitless lust. This preoccupation with lust as a sin was, of course, a matter of huge hypocrisy. The celibacy of priests has been ordained by the Second Lateran Council of 1139. That did not prevent many priests having secret marriages or covert mistresses whilst judging the sexual morality of the population often at church courts. We don’t have the church courts any more but the hypocrisy continues to this day, does it not? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The original fifteenth century rood screen. Right: Kept in the upstairs rooms, this is the chest dated 1629 in which the important documents pertaining to the hospital would have been held. There would have been three locks and three keyholders so that no individual could steal or tamper with the contents. One of the keyholders was the vicar of All Saints Church almost literally a stone’s throw away for an Olympic javelin champion. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The upper hall, now known as the Audit Room. The chest is on the left. Originally, this was a Guild Hall for the Guild (or Gild) of All Saints of which William Browne was the leading light. The Reformation ended the religious gilds so that latterly it became the place of administration, hence its name. The table - woe betide you if you put anything on it! - is over five metres long and bears the date 1583., five years before the Spanish Armada! There is a doorway to a gallery overlooking the chapel so that the sick could still hear mass. Right: The Confrater’s Room. Until 1720 the Confrater shared the Warden’s accommodation on the east side of the hospital quadrangle but the incumbents had a bit of a barney! The Confrater stopped living on-site but retained this room on the upper floor as a sitting room for when he was on duty. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

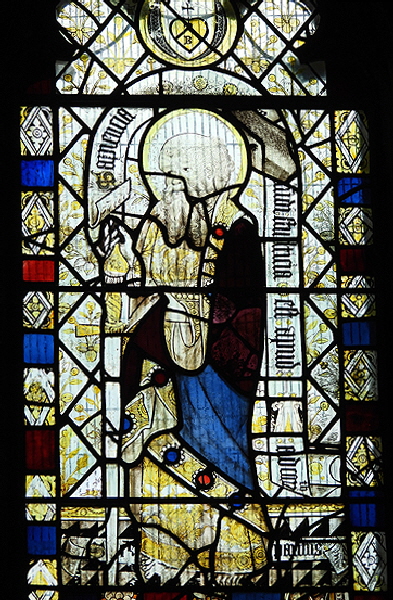

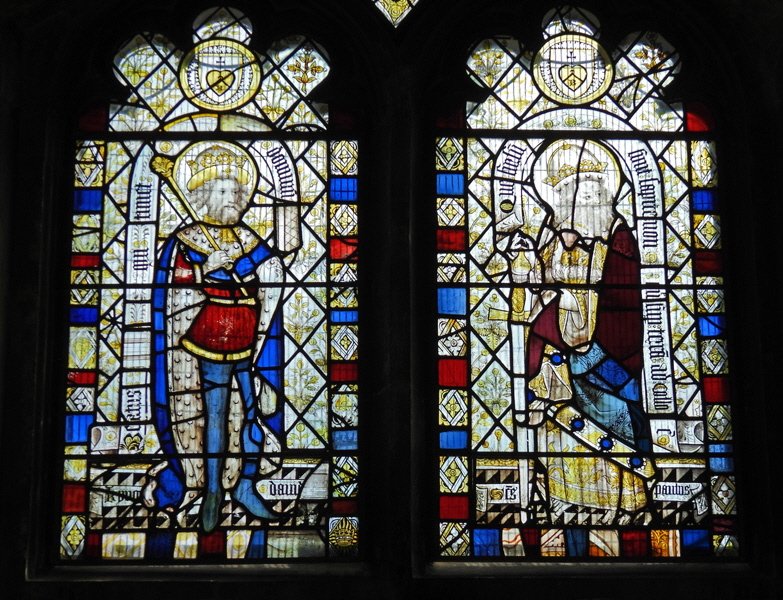

Left: King David. In the top light is a stork device, one of the symbols of the Browne family. Possibly it was a rebus of the name Stokke (Stock) (of Warmington, Northants) , the maiden name of Margery, wife of William. Centre: St Paul with his sword. In the top light is a heart shape with a letter B and a cross. This was William Browne’s merchants mark, Right: Composite figure wearing a doctor’s hat. The Browne merchant mark appears again here. The appearance of the Browne family crests in this area, we must assume, reflect that this was a space for the gild and William was anxious to put his family stamp upon it. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: King Solomon with the Browne stork in its top light. Right: Kings David and Paul. These are NOT the same images in the pictures above. David is wearing the same fetching blue pantie hose and red mini-skirt in both but look carefully and you will see that the face is slightly different and that the top light has the merchants mark rather than the stork, Paul still has his sword and the merchant mark appears as it does above but his head is completely different. This glass is all very wonderful especially with its associations with the Browne family. The use of glass jewels suggest the same glazier as in the chapel glass. It has been suggested that it was John Glazier of Stamford who did similar work at Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire. King David’s anachronistic mediaeval togs are a bit of a scream, aren’t they? |

|

|

||||||||

|

Left and Right: Stork imagery in, respectively, the entrance passage to the Hospital and in the Common Room As you can see, the glazier was not quite able to reproduce it consistently! |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: A panel from the window in the entrance passage. On the left is William Browne’s own arms: “three mallets sable” and on the right his arms conjoined with those of the Elmes family into which William and Margaret’s daughter, Elizabeth, married. Right: The Browne merchants mark in the entrance passage. |

|

|

|

Left: The present day Hospital accommodation, built in 1870. Right: The north side of the main building with the warden’s accommodation to the left. (Photo: Bonnie Herrick) |

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The entrance to Browne’s Hospital on Stamford’s Broad Street. (Photo: Bonnie Herrick) Right: The Browne insignia on the warden’s accommodation. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: A cheeky dragon peers out from the drip mould of one of the exterior arches in the quadrangle. |

|||||||||||

|

Footnote - Stamford Endowed Schools |

|||||||||||

|

Most people living in Stamford would, if shown William Browne’s stork crest, say it looked vaguely familiar but would not perhaps always be able to say why! Where it is is seen most is on the uniform badges of the pupils of Stamford’s so-called “Endowed Schools”. Along with Burghley House and the famously expensive “George Hotel”, the independent Stamford Endowed Schools is one of the three high-profile institutions within this historic town. With several buildings dotted throughout the town, you won’t go very far without seeing its crest. You might reasonably wonder if William Browne founded the school. In fact, Stamford School as it originally was called was not founded until 1532 by William Radcliffe, another rich merchant and also MP. One of its earliest pupils was William Cecil who, of course, went on to become the chief advisor to Elizabeth I, a post later enjoyed by his son Robert. It was the Cecil family, of course, who went on to build that other Stamford icon, Burghley House. The school has been part of the town ever since. In 1871, through a process that I won’t bore you with - not least because I’m not sure I understand it! - the Governors of Browne’s Hospital were persuaded to put some of the surplus funds from William Browne’s charitable endowment at the disposal of Stamford School and a sister school, Stamford High School. Together, they became the Stamford Endowed Schools and adopted William Browne’s stork crest. I wonder whether William would have approved of all this? In any event, it is astonishing to think that his financial legacy was sufficient for its still being in substantial surplus nearly four centuries after his death! |

|

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

|