|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

intersecting lines of tracery, typical of a late thirteenth century date. Thrillingly, the mediaeval glass is intact as it is in two more of the chancel windows. The glass alone here is well worth the visit. As if that were not enough, there is also a collection of Flemish painted glass roundels within the church. This is quite a “thing” with many churches sporting a few. What I have not been able to find out is why they are here at all. As with many churches the roundels sport Dutch or Flemish words so it does not seem they were manufactured for sale in England. There must have been quite a trade but why? Within the chancel are some benches dating from 1535. That is quite late for mediaeval poppy heads - as opposed to Victorian ones. They are large and ornate and, by eschewing pre-Reformation imagery of saints they avoided visits by lunatics wielding hammers and chisels. They are still very interesting, however, with a range of monsters - which were perfectly acceptable in post-Reformation England - and heraldry. It is an unusual set. Most unusual of all, if you believe it, is the poppy head showing two “Red Indian” heads, supposedly with headdresses. Bizarrely, in my view, Simon Jenkins makes these the headline feature here above the fourteenth century glass and doesn’t even mention the pre-Conquest crosses! Personally, I am sceptical. The seat backs are of “linen fold” design, another Flemish trope that became popular in England during the sixteenth century. You can read more about this in a footnote to Fawsley Church in Northants. Interestingly, Fawsley also has some Flemish glass. Were the merchants of England importing a variety of Flemish work to adorn their churches? As with so many churches, it is the contents that excite here rather than the architecture. Jenkins and Pevsner before him undervalued it in my view. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking east. The uninterrupted curve of the lofty chancel arch and the huge east window beyond it make for a spectacular vista. There is, surprisingly, no sign of a rood loft. Perhaps the clue is in Pevsner’s statement: “A very curious church; for much of what we see, be it apparently Perp or be it apparently earlier, is done or re-used by early C17 masons” Right: Looking to the west. There is another spectacular arch to the west tower. Like the chancel arch is appears to be Decorated style. The arcades do not match at all. The south aisle capitals look to be late Norman but this surely is not the original height of the arcade. Looking at the old roof line just visible on the west wall, I think it is safe to surmise that the both arcades was raised in 1620 when the clerestory was built. by Pevsner’s “early C17 masons”. The Church Guide suggests (seemingly repeating speculation) that it might have been rebuilt in the fourteenth century after structural problems but I still think it unlikely it was built to its present height The north aisle looks. to be of Early English origin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The very curious font. Top Left is the donkey, or if you find that hard to believe, an agnus dei. Or any old animal you care to nominate although it would be a darned strange lamb, it seems to me,. The rest is a bonkers seemingly random selection of triangular shapes. As previously stated, the church believes it might be pre-Conquest and. as I have said elsewhere, churches rather enjoy the supposed kudos of a very early foundation date. Pre-Conquest fonts are few and far between so we have to be sceptical. It is very easy to equate crudeness with pre-Conquest but there are plenty of even more childlike fonts of unimpeachable Norman origins. That said, there is nothing “Norman” looking about it either and an ancient font is far from impossible for a church that sports three pre-Conquest churchyard crosses. I am also intrigued by those strange carved “columns” with little Ionic curls. The do look vaguely pre-Conquest but maybe that is just fanciful. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

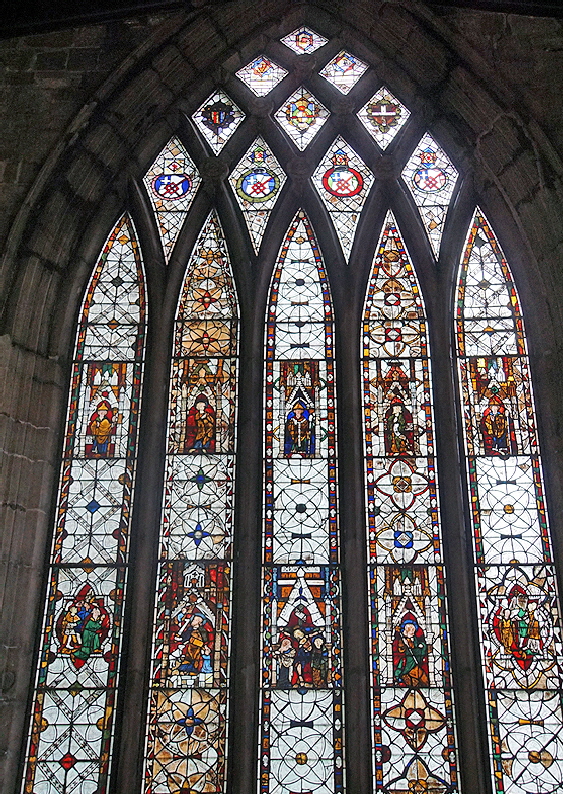

Left: The East Window of around 1380. It has ten historiated panels and the top lights have heraldry. Right: Henry II, having caused the death of Thomas Becket is kneeling barefooted in penance and being given a damned good thrashing. This and Becket’s murder (see below) are fortunate survivals, Henry VIII, having separated Church from State and having assumed supremacy over the Church did not take too kindly to the memory of Becket who had, of course, defied his predecessor. And the notion of a King doing penance on the orders of a Pope horrified King Hal. Most Becket imagery was destroyed at the Reformation. I rather suspect that the reforming zealots either could not see these glass panels well enough or did not recognise them for what they were, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A young apostle, supposed by the Church Guide (which is excellent on this subject) to be St John. Centre: Becket in bishop’s robes. Right: St Thomas is holding a scroll upon which is name is written. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

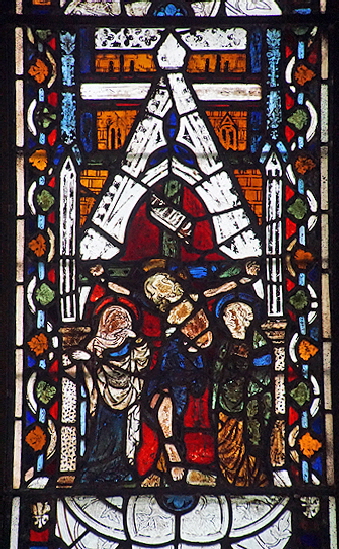

Left: The Crucifixion Centre: The murder of Thomas Becket. Right: A stained glass representation of (forgive me) I think is one of the ugliest stories in the Old Testament amongst some stiff competition. Abraham, sword in hand, is about to slaughter the cherubic Isaac to prove the depths of his devotion to his God. Just in time, God stays the execution, satisfied with Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son. To Abraham’s left the lamb is caught in the ticket. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

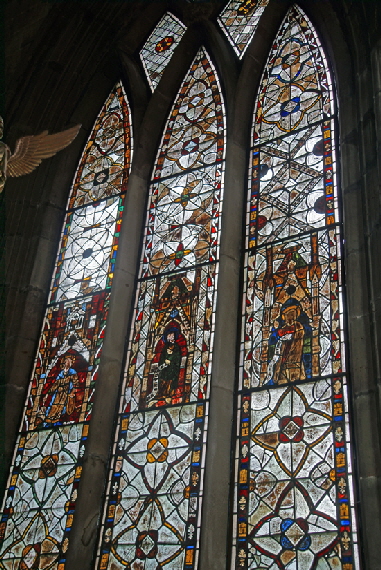

Left: The mediaeval window on the north side of the chancel. Centre: St James Right: A clearly reconstructed Madonna and Child. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The mediaeval south window of the chancel. Centre: Moses with the commandment tablet in hand. Right: St John. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The monument to Godfrey and Margaret Foljambe (d.1560). It is said by all to be alabaster but has none of the fine carving one associates with that material. Are the effigies of stone? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The poppy heads in the chancel are an interesting collection. Dating from 1535. they are quite late mediaeval and very different from the poppy heads we are used to seeing in the south east of the country, especially that hotbed of the craft - Suffolk. There is nothing religious here so they have escaped mutilation. Left: The supposed “Red Indian” heads that Jenkins bizarrely regards as the headline feature of this church. I am quite sceptical about them. The first Englishman probably reached North America very late in the fifteenth century: possibly John Cabot or - as is now emerging - an associate, William Weston. Such an explorer would have needed to have met the native people, survived the experience, sketched the people and then returned safely to England. Then a carpenter in Staffordshire would have had to have seen the pictures and translated them into the unlikeliest of church decorations. Impossible? Not at all, although to my untutored eyes these headdresses look even more reminiscent of those seen by the Conquistadores in Latin America. Well, anyway, it’s great fun to speculate. Right: Two maned serpents eat heir own tails in the way maned serpents were wont to do, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The initials “AD” of Anthony Draycott who had the stalls installed here. Right: The Draycott family arms. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Love this old man. Note the cross at his neck and also the carved foliage. Right: Two more monsters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A nicely-carved coat of arms. Right: Two more...yes...two more monsters! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This creature has a forked tongue. Centre and Right: These little heads in the timber roof are not remarked upon even in the Guide Book, but I like them! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flemish or Dutch stained glass roundels of the seventeenth century, installed here in 1874. They are the “Labours of the Month”, a ubiquitous theme in English church iconography in wood and stone - especially on fonts. Depictions in glass, however, are much rarer and these roundels were made long after the theme became unfashionable in England. Such roundels are surprisingly common in England - but they are never English! England did not produce “pot glass” - where pigments were fired “in the pot” during the manufacture of the glass. When Louis XIII of France went to war with Duke Charles IV of Lorraine in 1633 the Lorraine glass glass-houses were destroyed, leading to almost two centuries in which hardly any pot glass was used in England. The roundels we see here are not of pot glass, but of glass colored with enamel paint that was made from melting ground-down coloured glass. It was painted directly onto clear (“white”) glass and then fired in a kiln. This removed the need for different pieces of coloured glass held together by lead in the traditional way. Presumably wealthy merchants were happy to buy these roundels for their local churches when they traded with the Low Countries to make up for the non-availability of traditional coloured glass. Whether they donated them or sold them, I do not know! The diamond-shaped panes of glass that surround the roundels are, by the way, known as “quarries”. |

|

|

|

Left: The south porch. Right: Quadripartite vault of the south porch. The Church Guide speculates it might have come from the suppressed Croxdon Abbey nearby. |

|

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left: The north side. Note the rosettes at the junctions of the chancel window tracery. Centre: The tower from the south. Below the bell stage it is a Norman structure and all that remains of that period besides the font. Right: A louvred Norman window. |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

You may View or Download a .pdf Version of this Page Below |

|||

|

|