|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

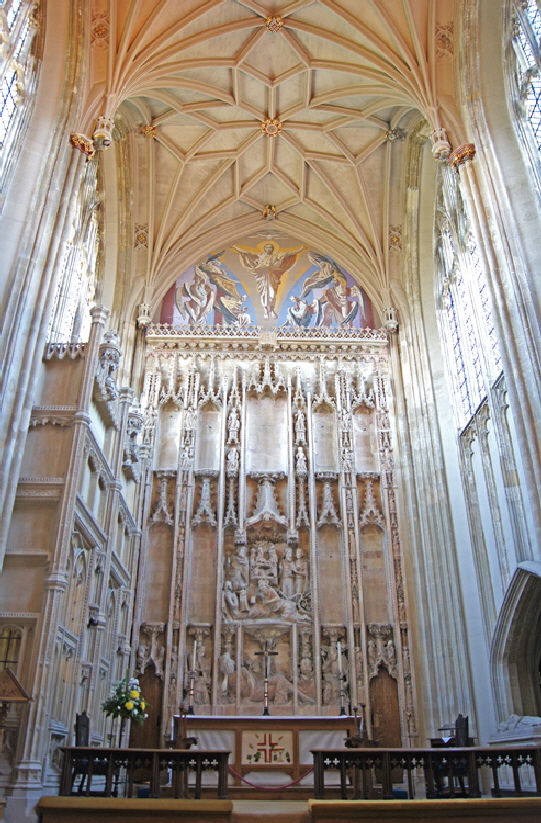

There was a monastery here at the Domesday Survey in 1086. It was inhabited bywenty-four so-called “secular canons” who did not follow a monastic “rule”. Those that did follow a rule were known as “canons regular”. his allowed the secular canons much more freedom to serve the surrounding communities. The Monastery was called Holy Trinity and at that time the town was known as Toinham. In 1094 a new building was started by Ranulf Flambard who was later Bishop of Durham. This date reflects the way in which after 1066 the Normans consolidated their temporal power by the building of castles before proceeding to put their energies into building and rebuilding of religious buildings. It was started only one year after the start of the iconic Durham Cathedral. It took until 1150 for the building to be completed by which time the monastic incumbents were canon regular observing the Rule of St Augustine. Its high altar dedicated to Christ the Saviour led to the change of the town’s name to Christchurch. Of that Norman building the nave, aisles and transepts remain. The nave has the “normal” three tiers of arcade, triforium (gallery) and clerestory but the Norman building had only the bottom stages, the clerestory not being added until 1290. It has double lancet windows in the later Early English style you would expect in 1290. Uncharacteristically, the north side is the more attractive, the south side having suffered a little from the removal of the monastic range at the Reformation .The Norman blind arcading is more extensive on the north side. For the Romanesque lover the Norman stair turrets in the transepts steal the show along with the lovely little apsidal St Stephen’s Chapel in the south transept. The original chancel was apsidal. It was replaced by the “Great Quire” at the latter end of the fifteenth century in Perpendicular style. The superb reredos was completed between 1330 and 1340 and originally stood in the Norman apse. It must have been some apse! The choir stalls are, as you might expect, splendid and there are thirty-nine misericords amongst the fifty eight stalls. As always with churches of this size, there is a limit to how much I can write here. The photographs should whet your appetite so get you little bottoms moving in that direction, especially if you are on holiday in Bournemouth only six miles away. Is this one of the top eighteen churches in England? It might not be in mine but it would certainly be in my top fifty. |

|

|

|

Left: The north side. The north transept with its blind arcading and gorgeous stair turret is clearly Norman despite the rather uninspiring north window. The tower dates only from the fifteenth century. I presume that his dates from the building of the Great Quire because this meant that the original central tower must have been demolished. Right: Looking towards the north transept with its original Norman arcading and windows. To the right we can see the north aisle windows which look to be late thirteenth century, although the wall is the original Norman. These almost mirror those of the north side. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Great Quire with its own clerestory of huge Perpendicular style windows. The quire aisle windows are later. The Lady Chapel here is behind the altar and is the square structure to the left of this picture. Right: The north transept with its rare and gorgeous stair turret. A stair to what? Well, there was originally a central tower and crossing here. I presume the stair led into the triforium level and gave access to both the tower and to the rood screen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north stair turret (sorry to keep banging on about it!) is a precious survivor of the Norman era. There are three levels of blind arcading (note the barley sugar twist on one of the columns at ground level) and that wonderful course of criss-cross moulding. Right: The north porch which provides the entrance to the church. It is thirteenth century Early English style. The monks, of course, would have had their own entrances from the conventual buildings on the south side so this must have been for the great unwashed and unordained. It pre-dates the west tower and so the west wall of the nave would have terminated the building in line with the right side of this porch. That begs the question of whether this doorway replaced an earlier one in this position or whether there was also - or only- a Norman west door - perhaps similar to the surviving one at Tutbury in Staffordshire - that was lost when the tower was built. Malmesbury Abbey in Gloucestershire, also a Norman structure of similar original floorplan to Christchurch, still has Norman west and south doors (the conventual buildings having been to north rather than south). The south door at Malmesbury is one of the glories of Anglo-Norman architecture and I rather suspect that Christchurch we lost a similarly impressive doorway. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north doorway with its vaulted porch. Right: The rather untidy south side of the nave. The high level Norman doorway would, I presume, have been from the monks’ dormitory into the church but is has obviously been recut. Note the blind arcading to the right. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The nave looking towards the east. The arcades and triforium (gallery) are original Norman. This is a quite conventional configuration for a Norman priory building. There is a a walkway around the triforium. Note the decorative moulding to the triforium baluster top right. Beyond the screen is the Great Quire. The Norman church would have had a great crossing at the end of the nave supporting a central tower; and beyond that would have been an apse. The late afternoon light has tricked my camera. The stone here is in fact much creamier. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Norman aisle and triforium; Early English clerestory. This is a very instructive picture for showing the changes between Norman an early gothic architecture. Notice the lovely vaulted ceiling springing from the clerestory and imagine how much less light there would have been in this picture without the clerestory. It was a truly transformational change, one feels. Note the Norman blind arcading in the aisle beyond. Right: Looking west towards the enormous Perpendicular style west window. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking along the south aisle. This a vaulted Norman structure, characteristically narrow, but with a vaulted ceiling. Blind arcading runs the entire length. Right: This is the east end of the south aisle, flanking the quire. Look at the change in the fifteenth century vaulting compared with the nave aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Norman blind arcading and blind arcading in the south aisle. Note the capital carvings. Right: Triforium arch, with decorated capitals. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: For those who are left unmoved by chunky Norman architecture, the Great Quire (the church seems to insist upon that spelling, by the way!) will provide the highlight. It was built at the height of the Perpendicular style at the end of the fifteenth or start of the sixteenth century. The niches of the reredos would, of course, have been ablaze with painted statues that would have been destroyed at the Reformation maybe only three decades later. Note the beautiful lierne vault. A lierne is a rib that does not connect directly with either the centre or edges of the vault. Right: St Stephen’s Chapel. It was blocked off from the east side of the south transept for many years by an oak panelled screen, being opened up again as recently as 1997. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Decorated Norman capitals. If one thing is missing here for the dedicated fan of Norman architecture it is the joys of grotesques, beasties and pagan figures that make other Norman buildings so entertaining. Right: The choir stalls with their misericords carvings on display. Three hearty cheers for this. Inexplicably, some churches hide the carved undersides by keeping the seats in the down position. For undeterred and brazen sods like myself, that means taking off any cushioning seats, placing them none-too-carefully on the floor, and raising sometimes dozens of seats, And then enduring the embarrassment of dozens of crashes echoing through the church when I put them down again. Other churches - including Boston which has one of the best ranges of all - leave a token few in the up position. I’m sorry, guys, but we misericorderistas ain’t having it. Up they go (Bang!) and down they go (Crash!). Just why? It causes more wear and tear, especially if another of the Brothers and Sisters of the Misericords turn up later. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The magnificent Lady Chapel which extends east of the church from the quire ambulatory (the passage around the choir). Right: Norman glory. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are many interesting parapet carvings. Left: A strange double goats head, the top one with a central eye. I have seen this device on other churches. Just don’t ask me where! Right: You have to love this little craftsman peeping out from his hiding place. I think he is a carpenter - you decide for yourself. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Stalls and Misericords |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In truth, the misericords range here is far from being in the first rank. There are no less than fifty eight here and, for once, I am not going to show them all! A number of others disappeared or deteriorated beyond repair over the centuries. GL Remnant (who wrote the definitive catalogue of English misericords) dates nearly all of them to 1515 but one or two are reckoned to be earlier. To have so many reflects the prestige of this abbey in the early sixteenth century. Remember, this was not the parish church. Only monks would have been seated in these stalls. It is a rather odd set and we might wonder why the Abbey chose the finest sculptors but rather workmanlike carpenters? The subject matter is patchy, repetitious and relatively uninspiring (to our modern eyes, at least). Scenes of everyday mediaeval life - so often the most enjoyable - are conspicuous by their absence here. Even the hardiest of perennials - the mermaid, the pelican in her piety, the green man, are absent here although they might be numbered amongst those lost to the ravages of the centuries. .The designs are rather small and squashed. The biggest testament to their relative mediocrity are the “supporters”. These are the sub-carvings to the left and right of the seat and which are unique to the British Isles. On many ranges, these supporters (as the name implies) support the theme of the main design and are often entertaining or even outrageous. Here very few are carved at all and am incised diaper design had to suffice. All that said, they are one of the non-architectural highlights here. All things are relative and you certainly should not miss them because they are still fun! |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: A jester with long asses ears. Right: A peasant or jester is having his foot gnawed by a dog. Another creature attacks his posterior. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: Remnant’s Description: “A jester in a long cloak, with large face and ass’s ears, holding in his right hand a bauble containing a death’s head with pointed ears and belled hood, in left hand short, thick staff. You can see quite clearly here the unambitious supporters that characterise this misericord range. Right: A fearsome bat. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A man lying down. It is impossible to discern what he is throwing with his right arm. Right: A contortionist holding his feet in his hands. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A curiosity, this one. A beast of some sort but those limbs look too thin and the rear ones looks detached. Right: A man lying on his side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Remnant: “Small demi-demon with open mouth, long pointed ears, fat feet and extended claws, with his head on a cushion”. Right: Remnant: “ Crowned king, carrying a sceptre in his right hand and with long flowing robes, lying on his side supporting the bracket (of the seat”). Habitually, we talk airily of “a king” without thinking whether it was meant to be someone specific. At several churches I have been able to identify Henry IV (“Bolingbroke”) through his odd, cleft beard, most kings of the era being surprisingly clean-shaven. If Remnant is right with his 1515 dating - and he didn’t say how he knew this - then we would expect this to be Henry VIII. The Church Guide is less specific. Looking at pictures of Henry VII and Henry VIII’s coins I would say this looks more like Henry Tudor (d.1509) - the seventh Henry. This might mean Remnant is a few years out. Or maybe I am imagining the resemblance. The crown does vaguely resemble the one depicted on the head of both Henrys. I don’t think this is an idealised depiction. Indeed, I believe that coinage probably was what was copied by masons and carpenters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A monster very similar to the one above but with bat-like wings. Right: Another odd-looking creature with spindly legs and with wings. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

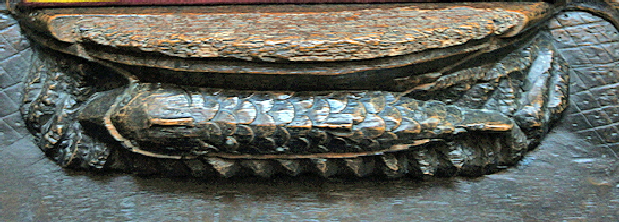

Left: A man with a ribbon passing around his back. Right: A salmon (according to Remnant) lying on rocks. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I can’t even find Remnant’s description of this! It looks like a contortionist and he is holding what may be a shield or a begging bowl which is being held in the beak of a bird! Right: Two dragons are flanked by foliage. Remnant dates this to around 1250. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A contortionist with asses ears and with a broken object (Remnaant suggested a snail) to his right. Right: An collared ape tied to a tree trunk, according to Remnant. A bear seems to me to also be a possibility. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The two misericords on this row are clearly different from the others. The seats are different shapes from the others and the designs have been less obviously made part of the seat above. Remnant says they were found in a lumber room of the church but does not make the, to me, obvious remark that these two are clearly of a different era or a different carver. Left: The winged lion of St Mark with his gospel represented by a scroll. Right: A crowned angel holding a scroll. Oddly, Remnant does not draw the obvious inference that this is St Matthew in his own evangelical alter ego. Luke and John have clearly been lost to us. We have traditional supporters on this one - two legged animals with human faces. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A winged man or beast, a long creature with gryphon-like head behind him. Right: This is one of a few that I can’t match to Remnant’s descriptions. He talks of one with two rabbits, one of whom is emerging from a hole. Rabbits? Really? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This looks rather like it is meant to represent a real bat. Right: Yet another contortionist, arms outstretched, holding his feet. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the good things about the misericords here is that the amount of damage is limited - although we have to be aware that this is because many that were beyond repair were long ago discarded. I think also we can out it down to lack of complexity: many misericord ranges are much more finely carved with lots of vulnerable detail. This one of a man seemingly taking an axe to the seat looks to have been deliberately selected for vandalism as one wonders why? Right: Winged creature with the face of a man. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |