|

|

|

|

|

Dedication : Holy Trinity Simon Jenkins: ** Principal Features : One of England’s finest Doom Paintings

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coventry is not, perhaps, a city you would associate with an important mediaeval church. It is, unhappily, a monument to brutal post-war reconstruction. And also, one must say, one of many monuments to the brutality of total warfare that in one long air raid on 14 November 1941 saw damage to two thirds of Coventry’s buildings and at least five hundred deaths. Nearly all the mediaeval buildings were lost, including the Cathedral. All the more miraculous then that Holy Trinity Church, literally within a stone’s throw of the gutted cathedral, survived unscathed. Today it sits incongruously but proudly on the edge of the the city’s main shopping precinct. It is curated by a fiercely dedicated and proud cadre of volunteers. It is one of the largest parish churches in the country and its spire rises to 237 feet.

The Church Guide tells us that there was a chapel on this site in at least 1113, serving the Prior’s end of Coventry as opposed to the Earl’s end. They speculate that there was an Anglo-Saxon minster church here originally.

As you would expect of a city centre church, its architecture is grand rather than interesting and mostly in the near-mandatory late Perpendicular style and severely treated by the Victorians. It is cruciform in plan, however, and it is therefore no surprise to know that the church shows plenty of evidence of originally being of thirteenth century provenance. The chancel, extended in 1391, is longer than its nave. There are lavish chapels and aisles that bear witness to the wealth of mercantile mediaeval Coventry The chancel contains a nice little selection of misericords of which perhaps only one or two, however, set the pulse racing.

The big treasure here - one which staggeringly Simon Jenkins does not even mention in his “1000 Best Churches” - is its Doom Painting. It is perhaps the only one that can challenge St Thomas Salisbury for the title of “England’s Finest”. It was for centuries concealed, as is so often the case, beneath layers of whitewash. Rediscovered in 1831, an early restoration attempt caused Pevsner to write in 1966 that it was “totally blackened”. This was the result of an unsuccessful restoration in which a bitumen-based varnish was used. Remarkably in the nineteen eighties it was discovered that the majority of the painting had survived beneath its black coating. A painstaking new restoration taking several years culminated in an unveiling in 2004. If you are wondering why Simon Jenkins’s 1000 Best Churches” does not mention it, bear in mind that his book was first published in 1999 - although it still seems odd to me that he did not mention the painting’s existence or the restoration program which must have been in progress at the time. I am sure he did visit it....?

|

|

|

|

|

The really remarkable thing about this doom is that it is complete. Dozens survive in fragmentary form but at Holy Trinity, as at St Thomas Salisbury, we can see the artist’s complete canvas. All dooms show the same basics: Christ in majesty, usually surrounded by his disciples, the dead rising from their coffins to be judged. The sinners are carried off by luridly-depicted demons towards the Gates of Hell, the saintly lot head off smugly towards the the Kingdom of Heaven on God’s right hand heralded by angels. The damned side is always the more entertaining to our modern eyes and it always fun to see popes, cardinals and kings heading to the fiery pit. Here at Coventry, cheating ale wives are conspicuous amongst the sinners and we see something similar at Salisbury. This, one feels, was not the most respected group pf professionals. Why they were invariably women, I don’t know.

Most, though not all, such paintings are of the fifteenth century. This probably owes much to the preoccupation with death arising from the horrors of the Black Death in the previous century; and also with a new preoccupation with the notion of Purgatory. The clergy from the Pope downwards were all too willing to represent themselves as able to reduce the time spent in that wilderness in return for appropriate payments in coin or in services rendered. This hubristic and venal practice was at the anti-clerical centre of the Reformation and so it is no surprise that every single such painting was obliterated, usually permanently but sometimes, as here in Coventry, lying hidden for centuries.

Many people reading this piece will at some time visit the new and old Cathedrals just around the corner. One, of course, is a much-loved ruin; the other a splendid, if controversial, nineteen sixties treasure house of twentieth century art by the likes of Graham Sutherland and John Piper. Holy Trinity bridges the gap. Here you will see a large mediaeval town church with the work of mediaeval craftsman. To miss it off your itinerary would be perverse. Do go to see it and reward the dedicated people who keep it open and who will provide with all of the information you need. I will wager that for many of you the Doom painting of Holy Trinity will linger most in the mind after your day in Coventry,

Note: Pictures with “BH” in the captions are by Bonnie Herrick who accompanied me on this visit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The church looking east along the nave. Even Pevsner was vague about dating most of what we see. The west porch is Early English but what we see here is all Perpendicular in style of between 1360 and 1535. The crossing tower, I surmise, must have been early in that time bracket. If the original church here was of the Early English period (ie up to about 1280) then it is likely that there was a central tower here then since they were rarely built after this time. What we see, however, is not EE so I surmise that it was heightened and made more elaborate probably in the late fourteenth century. Centre: Looking to the west. Right: The modern font painted, I would like to think, of Aston Villa Football Club. What? You don’t think so?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And here is the Doom painting (courtesy Bonnie Herrick). The basic structure is the familiar one. Christ sits in majesty in the centre, flanked by his disciples. On the right (Christ’s left) Demons and devils are herding the damned towards the Jaws of Hell (bottom right) as they rise from their coffins on the Day of Judgement. In the top right had corner; and an angel blows the Last Trump, On the other side coffins are in considerable profusion, the dead rising still in their shrouds. They look pretty alarmed, as well they might. Top left are the gates to Heaven, Below Christ’s feet is a ball representing the Earth. On either side of this are the judged, both saved and damned. As usual, the painter has made a point - gleefully, I am sure - of including kings, queens, bishops and popes just to remind everyone that all are judged.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For we twenty first century observers the Devil’s side of a Doom is always a huge amount of fun. Not so, perhaps, for our mediaeval forebears who might have thought it was their possible ultimate destination! Or did they? A great deal is always made of their fears of the afterlife and, certainly, the richer members of society were seemingly preoccupied by the threat of Hell, hence the plethora of chantry chapels and the success of the Church’s own little racket of selling “indulgences”. After all, if you were rich what else did you have to spend your money on if not on the insurance policy of a chantry chapel and priests to pray every day for your salvation? But I sometimes wonder. We have all that evidence of the beliefs of the few but little idea of the beliefs of the many. I often wonder if many of our predecessors didn’t have a healthy scepticism about all of this? I wonder if many of them did not just shrug at the latest bonkers scaremongering about Hell? One might wonder why theirs was not a perfect crime-free society, given the torments supposedly awaiting perpetrators. Anyway, we have some great imagery here. Left: An angel blows the last trump. Dazed and uncorrupted corpses rise blinking from their coffins. The woman on the right has bare breasts. I know which way that hussy is going! Centre: Various delinquents are being herded towards the jaws of hell here. Three women are roped together at the bottom. the leading figure covering her breasts in all-too-late effort at modesty. Above them we see t a trio of women wearing fashionable headwear and bearing jugs, These are those perennial butts of the mediaeval artist - the alewives. Brewing was almost uniquely a female profession, much of the ale brewed in the home and sold either from there or from the local alehouse. They were the habitual targets of mediaeval satire and appeared on the undersides of misericord seats as well as on Dooms. St Thomas, Sailsbury has another fine example. Wikipaedia says :” Women in brewing and selling of ale were accused of being disobedient to their husbands, sexually deviant, but also frequently cheating their customers with watered-down ale and higher prices. While a 1324 record of offenses of brewers and tipplers in Oxford cites that offenses by women and men were relatively equal, most representations of ale sellers only negatively represented the women” . Images of alewives heading for hell, then, would have been popular. These three have added the sin of vanity to their rap sheets, wearing fashionable headwear. Given the sartorial laws which tried to control people dressing “above their stations”, I think there is a large measure of artistic licence in tis depiction! Right: The Jaws of Hell are particularly luridly depicted here. Three people burn merrily, There seems to me to be a preponderance of women amongst the condemned in this Doom!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: That’s John the Baptist on the left of this picture. Right: Beneath the feet of Christ and his disciples a group of figures awaits its fate. Note the stigmata on Christ’s feet and the orb of the world between them. Note particularly the image of Mary just above and behind this group. She offers her breast to Christ in supplication for the mercy of the risen. Christianity created a whole non-scriptural career for the mother of Christ including this one of pleading the cases of those being judged. She often appears at the elbow of the Archangel Michael as he weighs souls in his scales. See the example from Slapton in Northamptonshire shown at the end of this page.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disciples either side of Christ

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The north side. The dead rising from their coffins. Top left some of the saved are on their way through the gates of Heaven. Unusually, the painter did not make much of this particular bit of the painting, Above: The walking dead.

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking up into the central tower with its three stages of windows and arcading (BH) . Right: The beautiful gilded ceiling of the tower.

|

|

|

|

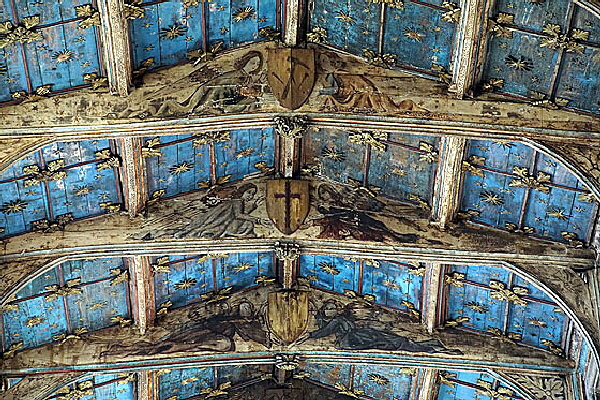

Left: A portion of the striking nave ceiling painted in blue and gilt. The central shields held by the angels show the instruments of the passion. Right: Fragments of mediaeval glass reassembled into the usual crazy pavement configuration. They are a common site in English parish churches. You might reasonably wonder why? Myself, I aways welcome the recognition of the idiosyncratic, luminous and lovely art form of mediaeval glass, often as a counterpoint to the garish colouring and stiffly formal compositions of the Victorian glaziers who often overwhelmed and darkened the churches they were tasked to illuminate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Misericords

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of the best pictures are by Bonnie Herrick (“BH”) - who, unlike my lazy self had the patience to set up her tripod. Left: (BH) An angel. Right: (BH) A closed door within a porch supported by Tudor roses. The closed door, according to GL Remnant, is a symbol of the virginity of Mary.

|

|

|

|

Left (BH): Another woodwose locked in combat with - perhaps - a lion,. This one still has his club! Right (BH): This green man - another stalwart of English parish church art - is a particularly fine one. The face is very naturalistic. The leaves are oak, as is the tradition in England although this is imagery found all over Europe. They surround rather than obliterate his face: he is not hiding within the leaves but proudly fronting up to the world as a man. A magnificent example of this ubiquitous yet mysterious character about which so much speculation has been made and so much earnest well-meaning claptrap has been written .

|

|

|

|

Left: The south aisle. looking east through the Jesus Chapel (the south transept) towards the south chancel aisle. Centre: The east window is by Sir Ninian Comper. It is called the “Bride’s Window” because it was financed by contributions from couples who were married there during the forties and fifties. The original was blown out during the Blitz.. Right: The spire.

|

|

|

|

Slapton Church in Northamptonshire has this superb example of a wall painting showing Mary in her (non-scriptural) role as interceding on behalf of the sinners. The largely-obliterated figure of the Archangel Michael is holding the scales. On the right side is the soul being weighed. Mary puts her hand to the scale weighing it in his favour. It is a nice human - almost mischievous - representation of the Virgin interfering in the smooth running of the weighing room!

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future?

Please click here to see how.

|

|

|