|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

You might reasonably say that most churches have those qualities whilst being considerably older. It is, though, the wholeness of the interior that captivates; a feeling that you are seeing precisely what the congregation saw three hundred years before. This must be one of the few churches in England about which we know next to nothing in terms of its development. There never has been a village here: just scatterings of farms and cottages. There is no entry in Domesday Book. It was probably founded in Norman times and its basic shape still looks like it was from that era. The earliest mention of it in mediaeval manuscripts is AD294. But who built it? What patron put his hand in his pocket to build a tiny church, probably inaccessible other than by boat for much of the year, in the middle of a boggy marshland? Somehow, we know not how, it has clung on over the centuries, periodically modified and is still standing eight hundred years later. In his super little book “Tiny Churches” (AA 2016) Dixe Wills postulates the notion that this church was never well-built because nobody ever knew how long it would be needed even at the last rebuilding in the eighteenth century and that the work was, therefore, invariably slipshod. I can’t point you to any remarkable works of ecclesiastical or mediaeval art. But this church is a work of art as a whole. You are immediately struck (not literally, but it would be a close call for the tallest people!) by the four huge timbers that traverse the building and support the timber king post roof above. The timber frame of the building itself now encased on the outside by Kentish brick is visible throughout the church. If I told you the church was in Stratford-on-Avon and frequented by Shakespeare some of you might believe me! The prayer boards at the east end would give the lie to that, of course, since these were very post-Reformation tropes. Overall, it is certainly Georgian - but probably early Georgian. Apart from its construction, the real joy here is the painted box pews and the the three decker pulpit. They make the place a visual delight and rather put me in mind of Shobdon in Herefordshire. The pulpit is a hefty piece of furniture for such a small and low-pitched church. One little discussion point is the unusual - perhaps even unique - plain heptagonal font. Pevsner postulates it as “Perpendicular” (note to the late Nick P: that was a style not a period, mate) and maybe 1660s. He doesn’t say why. The information board suggests, more plausibly in my view, the fifteenth century. Not that it matters. Why heptagonal? Well. you can come up with all of the usual notions - six days to create the world and then another to rest, that sort of thing. We can’t know. But what I think is really odd is that it would be much harder to carve than the usual octagonal profile. Masons used what the great American writer Lon Shelby called “functional geometry”. In the absence of modern geometric instruments and Euclidian geometry masons found octagonal shapes easy. You draw out a square and then superimpose another square on top of it offset by ninety degrees and join up the points. Voila, you have the eight sides of an octagon. But a heptagon? How do you draw that outline easily? Of course. the mason was capable of it - but what a faff it must have been! Anyway, I will finish this little piece with more words from Dixe Willis that express my own sentiments perfectly: “This is not a church to pick apart and analyse but rather one to enjoy”. Let’s take a look. |

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south side. Note the newish looking brick. All of it, however, encases a timber-framed building. This is one church where square and rectangular windows don’t look out of place. They somehow complement the homely squareness of the place as a whole. Besides, the very low height of the walls beneath that shingle roof would only allow the meanest of faux-Gothic windows that would look anachronistic and silly. Those steep roof pitches are practical to clear rain and snow - Kent gets plenty by English standards - in this exposed spot. Right: The church from the north east, showing rather older brickwork plus, at the east end, that staple of old Kentish buildings, some weather boarding. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

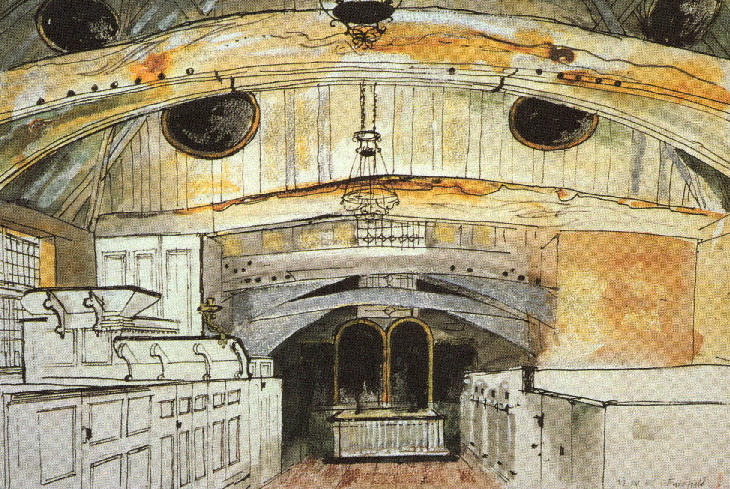

The interior looking towards the east. Intimate hardly begins to describe it. It is cramped with low headroom but somehow manages to get just the right amount of light inside. The altar has Laudian rails around it, designed to prevent dogs from desecrating it. Thomas Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633-45. Advocating “episcopalianism” - or preeminence of the the bishops, he believed in strict liturgy, lots of suspiciously Catholic-seeming ritual; and even Charles I who appointed him came to realise that his controversial views and policies did him no favours. He was tried in 1644 but the trial was inconclusive. Parliament had little patience with that outcome so in 1645 they passed a Bill of Attainder and beheaded the unfortunate prelate anyway. There is no separation of clergy and congregation here; and you would not expert there to be in a post-Reformation building. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

The altar area with its Ten Commandments and prayers. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Looking towards the west. The white painted pews provide a jolly note. Note the large family pew on the left. Who was that for, one wonders? Did they fund this rebuilding? |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the triple-decker pulpit. At the far end, the clerk would have sat - the vicar’s “helper”. The vicar himself would have sat in front of him - note the reading slope - and moved into the pulpit itself for his thundering, hell-raising sermon! Apart from being cramped as whole, the pulpit is actually oddly removed from the congregation, being squashed up against the north wall! Right: The lovely king post roof timbers. Kent has never been short of good timber.. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

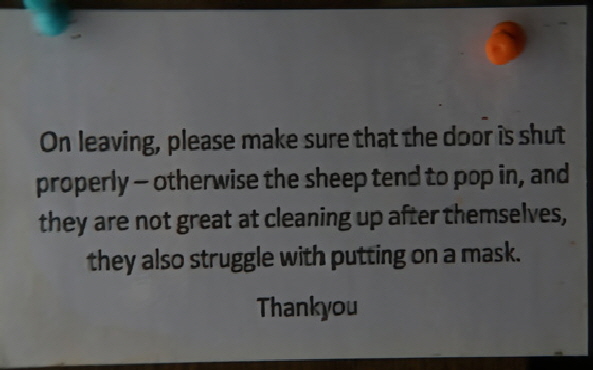

Left: That unusual heptagonal font. Right: Don’t you love England? You can also, of course, date this notice back to the dark days of Covid-19. I think sheep are better at putting on masks than they let on. I never heard of one of them becoming infected. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Marshland and ditches seen from the south side. Right: My church-haunting buddy and photography obsessive, Bonnie Herrick, posing on one of the bridges leading to the north approach to the church. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

A Note on Access The church is kept locked. Although it is far from being unvisited, understandably no keyholder wants to commit to crossing the boggy marshes twice a day in whatever weather is thrown at him or herself. A narrow road runs past the church and you can see the church quite clearly from your car window. The key is hanging up at Becket House about 200m past the church on the left hand side. It is quite possible that the key is already with another visitor so don’t panic if it isn’t there. You can always check with the very obliging owner if she is in. Retrace your steps for about 100m until, more or less opposite a little “lay-by” on the right hand side you will see a small metal gate that leads into the marsh. There is no footpath as such, so take time to work out your approach, given that you have to cross a bridge over a small stream. It’s not difficult! When you have finished your visit be sure to return the key or to hand it to any other visitor you might encounter on your way back. If you are both British you will then have a chance to cheerily exchange views about the weather. As we are wont to do. |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

You may Download and/or Print these Pages in .pdf format from the link below |