|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

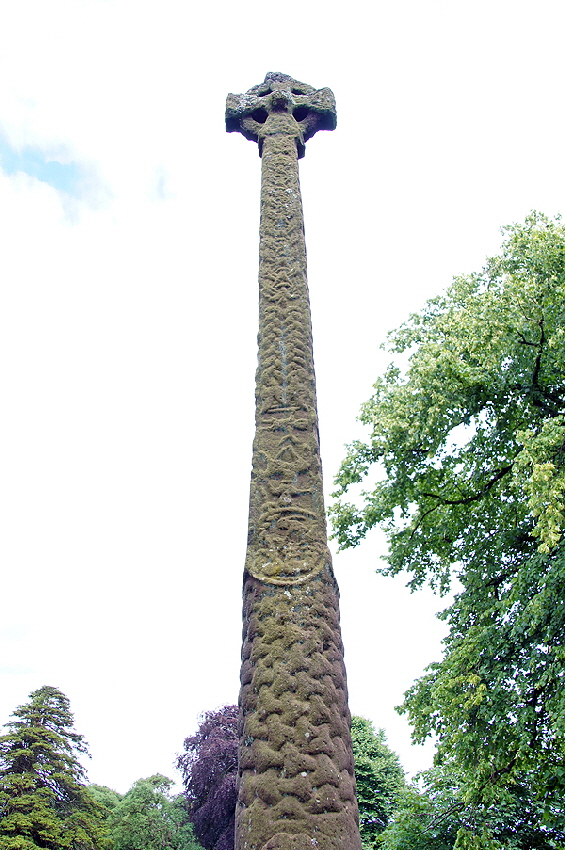

The reality - certainly with the Vikings - was far more complicated and in the Isle of Man and the north of England the evidence is plain to see that the Vikings usually adopted Christianity alongside their pagan gods, at least initially. Christian imagery juxtaposed with the heroes of Scandinavian sagas is not at all unusual. In fact, it is almost the norm. In Cumbria you can see the Tree of Ygddrasil (Norse Tree of Life) on a cross at Dearham. Loki - the evil Viking god - on a cross at Kirkby Stephen. Loki turns up again at Middleton in Yorkshire. On the Isle of Man you can see Odin on one side of a cross and Jesus on the other. Anyway, so to Gosforth. Gosforth has one of the most spectacular churchyard crosses of them all. At over fourteen feet it is definitely the tallest. It is also slender and its intact preservation is something of a miracle. Nothing else comes close. Its sides have been so extensively sketched by antiquarians that it is something of a shock for find that the eleven hundred year old carvings are hard - although not impossible - to make out. There has been huge academic debate about the imagery. There is a reasonable consensus about most of the imagery and it is all straight out of the Viking books of legend. Only a crucifixion scene is recognisably Christian and even then three Norse gods - Odin, Baldr and Heimdal - are viewed as probably alternatives to Christ himself. There is much to be said as to why all of this pagan imagery is seen on a Christian cross and I discuss the issue briefly below. The best estimate of the date for the cross is AD930-50. As if that were not enough, the church houses two precious examples of hogback memorials. The function of these, which are almost unique to the north of England and, astonishingly, unknown in Scandinavia itself, is a matter of debate. Graveyard monuments is the obvious answer and one of the Gosforth stones even has a crucifixion scene, For more discussion of this see my page on Heysham in Lancashire. They are unequivocally and thrillingly Viking in origin. Both are later than the cross - one perhaps of AD1000 and the other perhaps AD1050. Then the church gets really greedy because it has a collection of other stones including the famous “Fishing Stone” with more exciting Viking imagery. The church itself struggles to match the delights to which it plays host. Probably there was a church here before the Conquest, although the presence of the churchyard cross does not confirm this. Did the cross come to the church or did the church come to the cross? Quite possibly the cross was erected near to or on the site of a pagan shrine or perhaps it was just designed to attract people to a place where the word of God could be heard from itinerant preachers or monks. Perhaps an Irish monk occupied a tiny oratory, similar to the “keills” found on the Isle of Man. We cannot know. The first stone church was built early in the Norman era and probably of just two cells. A few fragments remain and some of the south wall is believed to date from that time. In the thirteenth century it was all more or less rebuilt in Early English style. The chancel is of about the fourteenth century, its arch - according to Pevsner - resting on the remains of a Norman one. In truth, however, we can more e less ignore the building itself save for a couple of strangely anachronistic-looking Norman style with faces. I rather suspect this points to an early rather than later thirteenth century structure. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Views to the east taken from (left) ground level and (right) the little gallery at the west end. The chancel is probably fourteenth century but the church underwent considerable Victorian remodelling. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the west, There is a curious little loggia between two west windows that look Early English but date from a remodelling of 1789. Right: Looking across to the Early English north aisle. To the left the two hogbacks can be seen on display. Also just visible is the doorway through to the north chapel from the aisle. Mounted above it are several pieces of sculpted stone. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: These capital carvings are on the the reverse of the chancel arch and clearly pre-date the current church. They must be from the Norman building. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A curiosity. I will simply quote the Church Guide: “...cast in 1839 it was captured by Sir Humphrey le Fleming Senhouse at Annunghoy in China in 1841 (during the Opium War) and presented to the church in 1844 by his widow”. Chinese bells don’t have a clapper so the local blacksmith made one! Right: Clock mechanism. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

The Gosforth Cross |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Most academics seem to agree about what is represented on the cross here. The most remarkable thing is that this a cross which has, apart from the cross head itself and a possible crucifixion scene, no Christian iconography whatsoever, and even those two items are open to interpretation. It is a mass of writhing serpents and scenes from the Viking legends. Reconciling this ambivalence is not easy. Nor is the Gosforth Cross a one-off in this respect. Many of the Isle of Man’s extraordinary collection are also awash with Odins and Thors, sometimes accompanied by Christian symbolism, but often not. To the casual visitor, this would be a jaw-dropping realisation. There are, however, rational explanations. Which you believe is probably as much a matter for your own personal mindset as anything else. Let us start with the whole thorny issue of the conversion of the Vikings to Christianity. When talking of the Anglo-Saxon conversion it is fairly easy. Although I am intensely sceptical about the notion that Kings converted and their populations slavishly followed, it does seem that top-down was at least an important element. It seems too that the Christian hierarchy - its bishops having been appointed by Kings - was in a position to bully the ordinary people to some extent. The thegns of these kings would themselves of course probably convert through political expediency. Doubtless the ordinary people often paid lip service to their new God or else just added him to their existing pantheon headed up by Woden until eventually the old beliefs just dies out.. It is not difficult to see that a hierarchical and rooted society moved more or less in one direction. The Vikings were another matter. Although they became rooted in England, and although Kings of the Viking lands themselves steadily embraced Christianity, it seems unlikely that the piratical and independently minded Vikings were so easily bullied into the new religion by the Anglo-Saxon priesthood. It is striking that Anglo-Saxon crosses do not preserve legends of the old Germanic religions, yet Viking ones do. In the case of Gosforth, it is worth remembering that the Norsemen of Cumbria did not, in the main, come directly from Norway but via their settlements in Ireland - especially Dublin which they founded - and the Isle of Man. In both places they encountered, absorbed and modified Celtic - not Germanic - culture. The Vikings probably arrived in the area in about AD900, and the cross was erected between thirty and fifty years later. This accords with the best estimates of the dates of the Manx crosses. Knut Berg whose wonderful article about the cross I use as the basis for all my writing here, pointed out : “The strong Irish influence on (the Norse) language proves that they must have been born and bred in Celtic lands. They must have become acquainted with and much influenced by Irish culture, and they certainly to a great extent married into Irish families. It was thus not a purely Nordic culture these Vikings brought with them to England, but a mixed Irish-Norse culture. It is reasonable to suppose that it was in Ireland that most of these Vikings had been converted to Christianity....The Irish, although converted to Christianity several hundred years before, had had difficulty in entirely giving up their pagan gods. These lived on in Irish myths only thinly disguised as historical persons”. It is now generally accepted, I believe, that the scenes on the Gosforth Cross are predominantly inspired by the Norse Voluspa poem that describes the creation, destruction and rebirth of the world. We do not see the creation here. What we see is the destruction and rebirth - the Norse Ragnorok that describes the destruction of the gods and the rebirth of the world. Parallels with the rebirth of Christ and the Apocalypse are obvious. and intentionally demonstrated here. What we cannot know is why this iconography is there. Why are we not seeing more scenes of the passion? Why do we not see the Biblical figures that adorn many Anglo-Saxon sculptures? Did the Norse cling strongly to their pagan beliefs and simply see Christ as just another god for their pantheon? A notch down from that, did they believe in this new God but simply insinuate him into their old mythology - a synthesis of the two belief systems? If you think that far-fetched, by the way, remember that Islam still shares Jesus and Abraham, amongst others, with both Judaism and Christianity. Christianity even appropriated the Jewish Old Testament more or less lock, stock and barrel because it suited their own world story! Did the Norse revel in the parallels with their old beliefs? Did the cross represent a simple intellectual confusion? Or perhaps a stubborn refusal by the Vikings to eradicate their old belief system in the way that the Christian priesthood truly craved - rather in the way that the Irish clung to theirs as Berg suggested? There are some startling reminders in our history of the “stickiness” of pagan beliefs. What are we to make of a land-grant made by Edward the Elder (son of Alfred the Great and the great re-conqueror of Viking held lands) in AD901 who begins the document “In the In the name of the High Thunderer, Creator of the world” by which we must assume he meant Thor! We can hardly suspect Edward of apostasy but this is surely an indication of a certain amount of syncretism between the old and new religions three centuries after Augustine arrived in Kent. As Thor Ewing said with splendid accuracy when discussing hogbacks: “...to a pagan, Christianity means the adoption of the Christian God; to a Christian it means the renunciation of the pagan gods”. I am sure this cross is a simple statement of Christian belief. But the Vikings saw no reason to abandon their great stories which were still loved, defined centuries of their culture and which seemed pretty complementary to the new religion; and which, moreover, did not challenge the notion of a single god. As an atheist myself, but brought up in my early years as a Christian, did I believe it all back then? Every Biblical story? Adam and Eve as a literal truth? How many practising Christians believe every jot and tittle of both Testaments? Sure, a Christian has to believe in some core things like Jesus as the Son of God, his crucifixion and his resurrection or he’s not a Christian. Did the Vikings believe in all of their gods and all of the stories as literal truth? And here’s the thing - did they all believe the same? Or like us, did they pick ‘n’ mix what to believe and what to pretend to believe. Go discuss. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

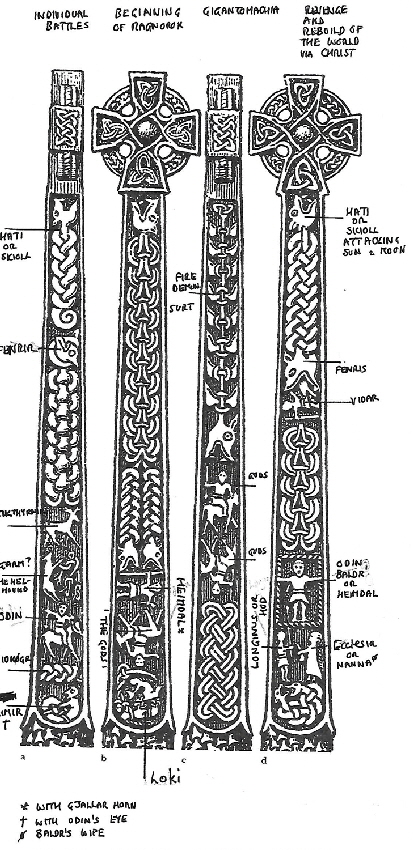

A sketch version of the cross faces that I copied from Knut Berg’s paper. In my not very good handwriting I did a few notes to remind me who all the depicted characters are. Refer to this as I go through the photographs! Note that the pictorial panels are all high on the cross stem. The base of the cross is circular in cross section but this changes to a square cross section halfway up and on these four faces are the historiated designs. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Let’s work through what we are likely to be seeing here. Start with the west side (b). This side describes the beginning of Ragnorok. See the man holding a horn in one hand and a spear in the other. This is Heimdal, the guardian of Valhalla, Odin’s mead hall where all Viking warriors expect to go when they die. His horn is called the Gjallarhorn and he uses it to warn the gods that Ragnorok is about to begin. He lives close to Bivrost Bridge and will defend it against the attackers, two of whom are assailing him already. The warrior below Heimdal is possibly a god riding to the battle. To complete the scene, a monster at the top of attacks the cross head which probably symbolises the sun and moon.. A the bottom Loki lies bound. His wife, Sigyn, holds a vessel that catches the venom from a snake. The onset of Ragnorok is prefaced by an earthquake and this will be precipitated when Sigyn’s basin is full. As she empties it, a drop falls of Loki’s face. His writhing causes the earthquake. The south side (a) shows two scenes. One interpretation of the lower one is that we seeing the mounted figure of Odin. who has come to Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life. The serpent below him is Nidhogr, the snake that gnaws the roots of the tree. Odin, unaccountably, has a short left arm. At the very bottom is Mimir. He has wisdom gained from drinking from a well. He is shown with a disproportionately large eye: one he has received from Odin for being allowed to drink of the well’s waters. This scene is of Odin seeking wisdom with which to fight Ragnorok. It is also possible this is Tyr, the only Norse god with a shortened arm. The upper part shows a hound jumping some vegetation towards a hart. He is probably Garm, the guardian of Hel (does that word sound familiar?). At the top of of the south side one of the great wolves - Hati or or Skioll - attack the sun and moon. Below him is Fenrir. So to the north side (c).The monster here is running downwards and not attacking the sun as on the other three sides. It has eight pairs of wings or flames attached by rings. This may be the fire-breathing Surt, the leader of the army attacking the gods at the battlefield of Vigridr. After the battle Surt sets fire to everything with his flames, including the homes of the gods. The east side is (d) has the most instantly recognisable imagery. There is a crucifixion scene. This is where it gets tricky. Is this Christ? The purely Viking-orientated interpretation is that it is Baldr representing a rebirth of the post-Ragnorok world. And, of course, this is precisely parallel with Christ which, one would have thought, was the whole point! Equally, there is ambivalence about the figures beneath the crucifixion. The left hand figure is easily identifiable as Longinus with his lance to be plunged into Christ’s side. It follows then that he right hand figure is St Mary Magdalene holding her pot of unguents. Another interpretation is that the spear holder is Hod, the blind god and the woman is Nanna, Baldr’s wife. Underneath is the Midgard serpent. Obviously if this was a purely Christian scene this would represent evil. But above this we have the Fenris-wolf, having already killed Odin, being himself slain by Vidar with his spear. At the opposite end of Fenris, Hati or Skoll is attacking the sun and moon! The ambivalence here is extraordinary and academics have been theorising about it all for decades. There is an entirely Christian explanation of the imagery and, let’s be fair, a crucifixion scene invites that. But I find it tortured an unconvincing. It was all carved by a Viking, Christian or not, and I think we must favour the notion that this is Norse mythology seen by the sculptor as a Christian allegory. Just how much weight he - and his fellows - put on one world view compared to the other is unknowable. How much were the Norse clinging to their old beliefs? By guess is that they continued to be part of the Norse culture and they were reluctant to abandon them entirely; and that the parallels between Ragnorok and Apocalypse allowed them to continue to portray their old favourites who were, let’s be honest, so much more fun than the po-faced monotheistic culture they had adopted! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west side. Looking at the historiated sculpture first, we see Loki at the bottom, Sigyn holding her basin to catch the snake’s venom. Above him is one of the gods riding to Ragnorok. Then Heimdal with his horn that announces Ragnorok to the other gods. He is already being assailed by a monster. Above that another monster assails the sun and moon in the form of the round cross. The monster’s body is formed by “ring-chain” ornamentation that is characteristic of the “Borre” style of sculpture which pertained from around AD840-970. Right: From the bottom: Loki and Sigyn, a god on horseback (inverted), Heimdal with his spear and Gjallahorn, then the monster. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The upper part of the south side. Right: The mounted figure is Odin on his horse Sleipnir. Below him is Niohogr, the serpent, Below him is (possibly) Mimir whose wisdom Odin seeks before Ragnorok. Above Odin Garm, the hel-hound, attacks a hart. Right: The east side. You can just make out two human figures: Hod and Nanna if you prefer the Viking interpretation, Longinus and Mary Magdalene if you prefer the Christian. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

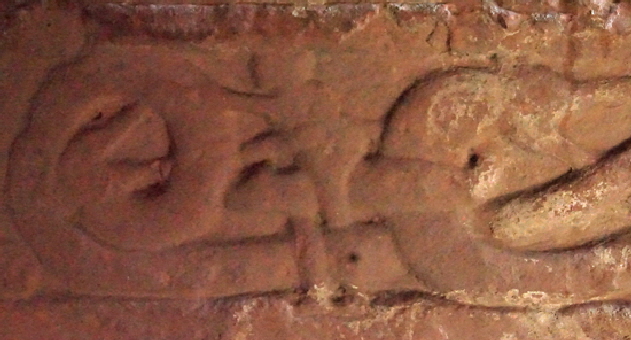

Left: On a cross we see either Baldr or Christ, again according to your point of view. Centre: Mimir with his one eye. Right: Interlaced pattern on the north side. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Odin on the back of Sleipnir. Centre: Two gods ride forth to Ragnorok. Centre: The wheel cross head that also represents the sun and moon. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The best way of seeing the Gosforth Cross in its full glory is to see the reproduction in the churchyard at Aspatria. Click this link to go there. |

|

The Hogbacks |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are a fair number of hogbacks in Cumbria. Often they are housed in the porch and really show only the faintest vestiges of decoration, often having been left out in the churchyard for a thousand years. In the churchyard at Penrith four (as well as ancient churchyard crosses) are still outside having weathered so much that they are not worth housing within. A sad state of affairs. The two on Gosforth Church, however. are very worthwhile survivals and this one - the “Warriors Tomb” - is one of the most important of all. It is so called because of the two lines of warriors facing off along the bottom. You can see their spears and, best of all, the overlapping shields - the shield walls - that were the favoured battle dispositions of armies at this time. For graphic accounts of what it must have been like to be in the front line of such a melee, I can think of nothing better than Bernard Cornwell’s “Last Kingdom” series. Imagine a heaving mass of men hacking at each other almost blindly with short swords through their shield walls while receiving the thrusts of the other sides and with spears thrusting through from the second ranks all this on a field stinking of blood and emptied bowels and you get the idea. There is a theory that the design here records the defeat of Ethelred the Unready (who was not unready at all, but “ill-advised” though that’s another story) somewhere near Ravenglass - only a few miles away - in AD1000. Well, maybe. But whoever was commemorated by this stone was probably a veteran of many battles. A warrior is shown at the end of the stone but I am afraid it is so badly weathered that my camera failed to capture the outline. “Tomb” is a pretty dumb expression. Nobody was buried inside. Although the stone probably had funerary significance it must have been as marker stones. As with the Gosforth Cross, Viking imagery is prevalent and Christian imagery is not. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Detail from the lower sections of the Warrior Tomb. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is the “Saints Tomb”, so called because at each end is an image of Christ crucified. It is taller than the Warriors Tomb. With both stones, the shape invites us to think of their emulating Viking “halls”., It has been suggested that the criss-cross design on the “roof” of this stone represents bands used to keep thatch in place. Look closely along the bottom sections and you will plenty of intertwined serpents. Like the cross, this stone probably represents Ragnorok. Note the serpent - the Midgard Serpent? - on the ridge. This stone has been dated as late as AD1050 by some authorities which shows that the Viking stories were still being conflated with Christianity’s own. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: On the Saints Tomb are some human figures. This one seems to be wrestling with the jaws of a serpent. Right: The two hogbacks together. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Christ crucified on the Saints Tomb. With his nimb, we can be sure this is Christ and not Baldr. Centre: The church has a number of other fascinating pre-Conquest stones. This, of course, is a coffin lid. Right: Arguably this stone is as interesting as the cross and the hogbacks. This is the “Fisher Stone”. In the boat is Thor, recognisable by his hammer, Mjollnir. The giant Hymir is on Thor’s right, his axe raised. Thor has baited a fishing line with the head of an ox and is trying to catch the Midgard Serpent. It personifies evil and has grown so big that it surrounds the earth and is biting its own tail. When the serpent was caught Hymir was so terrified he cut the line and Thor threw his hammer at it as it sank. At Ragnorok they would kill each other. Above it is another serpent. Above that is a hart. Whereas Thor and Hymir failed to slay evil in the form of the Midgard Serpent, the hart, symbolising Christianity is succeeding. The style of the hart is quite different from other carving in this church and should be compared with the hart shown on the Gosforth Cross. |

|

|

|

Left: This stone may just be a stylised flower decoration from a grave. It could also be a a “circle with arcs” design representing Plato’s “macrocosm” as identified by Mary Curtis Webb. It is fairly common in Cumbria and I have argued elsewhere that it was a concept probably imported to these islands by the Vikings and more specifically the Norse. Its is known as “Catherine’s Wheel” here which is, of course, nonsense! Right: The head of a tenth century cross. |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

|