|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

structure. Almost certainly the battlemented parapet was added in around 1400. This would have been the occasion of the sculpted frieze and in keeping with the extensive use of that decorative device in this areas of the East Midlands at that time. The Church Guide makes the surprising assertion that the tower was built in 1275 at the west end of a wooden nave and chancel. If this was the case, it is not something I have ever come across before and it is contrary to all commonsense, frankly. Who would build a hefty stone tower to abut a wooden structure that, had it still stood, would already have looked a total anachronism? Surely a stone nave would have been the priority? The author points the tower arch that has very clear evidence of an earlier nave and roof structure. Pevsner, however, with suggested that the nave walls were simply widened to their present extent and I think this is much more likely. The other thing worthy of attention here, is a set of “Vale of Belvoir Angels” slate gravestones. This is a niche interest, to be sure, but once they are pointed out to you they soon become something worth searching for in this area for their extraordinary durability and beautiful carving. See more in the footnote. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking east. This is a church that wears its Victorian “scraping” better than most. I hope you enjoy the Planetarium! Right: The chancel with its pretty Decorated style east window, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A pretty composition above the chancel arch adds a welcome splash of colour to the stone interior. The royal arms are of George II. Either side are eighteenth century Commandment Boards painted in oil on boards and presumably moved here from somewhere where they would have been readable by parishioners not in possession of binoculars! Right: The octagonal font is inscribed 1606 which is rather startling for a font that is clearly on Decorated style and surely fourteenth century. The inscription was certainly added later. It is oddly situated in the west end of the north aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The very unusual provision made in the chancel to house the church organ. Second Left: Looking towards the west of the north aisle. With its narrowness, I surmise this is part of the thirteenth century church. Second Right: The attractive Decorated style tracery of the east window. Right: The west tower. This looks to be of a piece with Decorated style parts of the church. The battlements - prohibited by security-minded monarchs until some time in the second half of the fourteenth century - were almost certainly added later and you can see how the masons incorporated limestone into the top tier of the tower to facilitate this. All this said, any certainty is confounded by the knowledge of Victorian restoration in 1874 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the nave is a whole series of nicely carved and elaborate floral carvings, of which these are three. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of a series of mediaeval grotesque corbels. Centre and Right: Two of the “Vale of Belvoir Angel” grave slabs. See the footnote below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The top tier of the tower. The battlementing cannot be the contemporary with the tower structure because it was illegal until well into the fourteenth century. As late as 1321 the University of Oxford protested that the parishioners of St Martin Carfax had crenellated an aisle “in the guise of a fortress to the disturbance of the scholars”. It is unlikely indeed that this was commissioned in isolation. Probably it was occasioned by the building of the clerestory. The frieze was no more than a piece of decorative indulgence by the stonemasons. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Frieze |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The frieze here is entertaining, but sadly weathered. What is the creature (left)? Both myself and my friend Bonnie Herrick who was with me and who took all of the greytone pictures think this is probably a flea carving indicating the presence of John Oakham who I discuss in my work “Bums, Fleas and Hitchhikers”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

You must make what you will of these images. There is a hornblower who is simultaneously scratching his bum, a hound with a hare or rabbit in his jaws, face puller and several fantastical beasts. Note also several holes - now partially blocked - that must have allowed the rainwater to run off the tower roof without any help from gargoyles. There are now drainpipes which must be a relief to any passing parishioners! Are these carvings consistent with their having been carved by John Oakham himself? The human faces are certainly evocative of those we see in other John Oakham locations where the flea carving is more obvious. The more John Oakham locations we find, however, the more obvious it is that the device indicated his presence rather than announcing his role in sculpting all of the carvings. The “look and feel” of them all is certainly in keeping with with other of “his” sites.. John Oakham was prolific. He was part of the “Mooning Men” lodge that worked in a broad band from Ryhall (near Stamford) and possible Thurlby to the east, through a cluster around Oakham in Rutland as far west as the environs of Leicester. But John is found in another wide area that stretches as far as Boston and Leverton on the edge of the Wash right through to the west of Grantham, many of which emerged years after I wrote my first book about these masons. That cluster included Harlaxton, Denton, Allington and, at its western extreme, Muston. Harby is nine miles south west of Muston so represents a perfectly plausible western extension of his reach especially given his, in mediaeval terms, extraordinary mobility. These “John Oakham” churches are not the only ones in the vicinity. Great Gonerby (near Grantham) and Plungar - only about three miles from Harby - have friezes that are certainly carved by the same mason and equally clearly not by the man who carved the frieze at Harby! They do not have flea carvings but frustratingly neither do other churches where John clearly was a contributor. So we have quite a conundrum. |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

People pay little attention to “label stops” - that is, the sculptures you often see at the ends of the drip moulds around mediaeval windows. Kings and Queens, real and imaginary, are almost ubiquitous . Floral designs, bishops and human faces often put in appearances. Harby, though, has a number of very ordinary-looking men’s faces. They surely are of real people or what would be the point? I wish I had a fiver for every time someone has airily informed me that such faces “must be” the faces of village “characters”, “patrons” and so on. I suppose all of these are possible. But - I think surprisingly - nobody considers the possibility that the masons were commemorating themselves. After all, many a cathedral proudly informs us of a master mason sculpture. At Fotheringhay Church in Northamptonshire they even suggest the the mason’s dog has been commemorated as well as the man himself! We know that masons got a pretty free hand at sculpture on parish churches. I rather suspect that patrons are normally shown - if at all - on the insides of churches whereas the masons exercised their traditional artistic freedom outside. One might even turn the question on its head and wonder why they wouldn’t leave their mark? We (including myself) tend to say that the parish masons are anonymous and faceless. But is this always so? That these are ordinary blokes seems to me to be fairly obvious and you don’t often see a clutch of them like this - these pictures show only about half. But there are quite a few such stops around in this area, including several of the Mooning Men Group lodge churches: indeed I am fairly convinced that one of my masons - Ralf of Ryhall - is portrayed at both Ryhall and Lowesby. Nearby Denton and Muston - incontrovertible John Oakham churches - have plenty of label stop heads too. There is no certainty here, but I think these heads are another little pointer to his presence here. |

|

Footnote - Swithland Slate and the Vale of Belvoir Angels |

|||||||

|

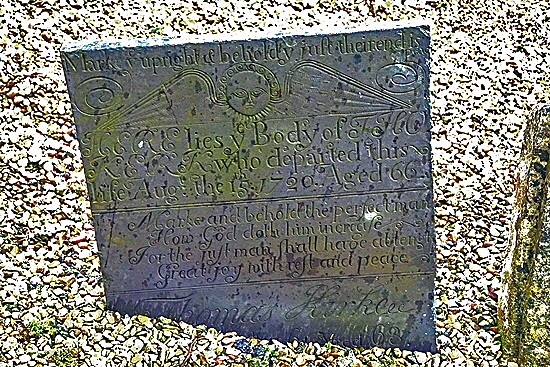

Churchyards and grave markers are not something to which I normally pay much attention but my “Church Buddy”, Bonnie Herrick who contributed some photographs from when we visited together, does. She loves skulls, hourglasses, skeletons and so. As is the way with these things, I have got drawn into it too, although I will never, as she does, travel to a church just to see a skull on a gravestone. And you think I am an obsessive? However, during recent expeditions in the East Midlands she introduced me to the so-called “Vale of Belvoir Angels”, of which there are a few examples at Harby. I quote her from the vale of Belvoir website : “Beautiful yet mysterious gravestone engravings that were loved by many but hated by a few. The Belvoir Angels began to appear on gravestones in the Vale from around 1690 until 1750. They were intricately carved angels with down-turned wings and a ruffed neck. It is thought they were commissioned by the wealthy parishioners wanting to leave their mark on Earth. Although the angels themselves were beautifully and meticulously carved, the inscriptions on the gravestones often contained grammatical mistakes, omissions and spacing errors, the mason running out of space on the stone before the inscription was finished. Although there are around 320 of these gravestones to be found in the Vale of Belvoir, virtually nothing is known about the stonemasons who carved them. It is thought it may have been a Father & Son, possibly based in the Hickling, Nether Broughton area. Certainly the later editions of the carvings are not as good as the earlier ones, perhaps one or both became unwell, eyesight failing. It is believed the stone masons were probably illiterate. However, it seems that not everyone approved of the angels. A fair few of the gravestones have been intentionally damaged or defaced. It does appear that the damage occurred soon after the stone was erected on the grave, probably by people of a Puritanical persuasion who considered the angel blasphemous. The monuments are made from Swithland Slate, found in Leicestershire’s Charnwood Forest. Roofing tiles were the main product. It seems that the number of monumental stones runs into several thousand covering a considerable area of the East Midlands, mainly in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. The earliest example is probably 1673 at Swithland Church and the industry continued well into the nineteenth century. Many of these sport quite artistic and fascinating graphics but the much smaller quantity of “angels” have become a particular focus of interest for some enthusiasts, despite their being repetitious. It seems to me there is no particular rationale behind this modern preoccupation beyond a wish to boil a body of work into more digestible chunks. A bit like that bloke that keeps banging on about “fleas”, “mooning men” and the like... That said, it would be a shame to pursue the angels to the exclusion of more interesting examples of the Swithland craft. I can’t comment on the assertion that the angels may have been all the work of a father and son team, except that it is wholly plausible as they are all so similar. When we look at non-angel Swithland monuments, however, it is a different matter. The masons sometimes carved their names and locations into the bases of the stone where it would normally be covered by earth. The first known example of this was about 1750. This presumably is part of the rationale for the two anonymous “angel” carvers having died or left the industry by this time. In a trip to nearby Thoroton many of the stones are laid flat and from my photographs I was able to spot: “J. Guy” Bottesford, “Collingwood” Grantham, “J.Simpkin“ Felicit (Lat. “he made”) and at Granby “S,Squire” Cropwell. So there you have it: yet another feature of parish churches worthy of our attention. Our churches are the gift that just keep on giving. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: An hourglass shows the inexorable passage of time on a non-angel Swithland monument. Right: Another Valoe of Belvoir angel at Harby. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

Sculptors marks, Thoroton Church, Nottinghamshire |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Graphic Carvings on Swithland Slate, Granby Leicesterhire |

|||||||||||

|

|

Death in the form of a skeleton wielding a spear in the act of taking a woman to meet her maker, an hourglass beneath his feet. Macabre! |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |