|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

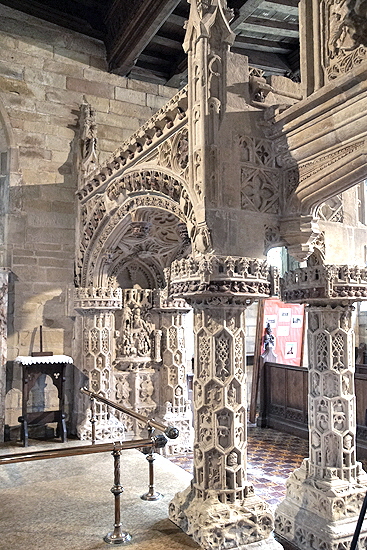

complete and his wife Dame Katherine Ferrers died in 1537. It was she who ordered the Babington monument to be built in the arch between the chancel and the chantry. She willed it to be made of alabaster but it was made of limestone, presumably to avoid the ruinous cost of so much alabaster. The use of the chantry chapel was short-lived. In 1545 Henry VIII, in typically rapacious fashion, decided that endowments were misuse of money and started to seize them for himself because he, of course, would never misuse money. Two years later Edward VI abolished them altogether. Not all Babingtons were recusant Catholics, and Anthony’s son John actually helped Henry in the Suppression of the Monasteries. This might explain why Kingston’s chapel was not despoiled. Pevsner is pretty dismissive of both church and, much more surprisingly, the monument of which more anon. We can certainly agree that everything west of the chancel and chantry are undistinguished and dates from two rebuildings of 1832 and 1900. The chancel itself, however, has Early English style chancel arch capitals and, most unusually, a tripe sedilia on the north wall. Was that relocated at some point? Either way, it seems that the chancel has some architectural connection with the Old Chapel before Babington began work on converting it to a church. So to the monument. The main structure is a narrow rectangle with hefty columns at each corner and arches to north and south. Above it are parapets with pinnacles at the corners. There is no tomb chest or effigy although the structure is of a shape to accommodate one. Although it is believed that Babington and his wife were interred beneath the canopy, there is no sign than an effigy ever existed and I would add that is difficult to see how such effigies, had they existed, would have been integrated into the canopy structure. It is something of a mystery. The whole structure is richly dedicated. Most numerous and charming are little carvings of people with “tuns” - large barrels. Some are children, making the rebus Babe-in-Tun. It is surprising, perhaps, to modern viewers but many leading families liked plays upon their own names and this was one such. Many shields are shown and represent the families from which the deceased hope to garner prayers to help ease their paths through the dreaded Purgatory. The columns have a number of figures and a whole raft of skeletons, believed to represent the Dance of Death. Of even more interest is at the east end of the monument where there is a remarkable sculpture of the Day of Judgement, complete with bodies rising from coffins, some being devoured by a voracious Jaws of Hell, others marching piously and gratefully into a doorway to the Kingdom of Heaven. It is plausibly believed that this was once the reredos of the chantry altar. Other sculpted panels to the west of the monument were originally on top of the monument but were subsequently removed as being too heavy for the structure. Pevsner said sniffily in that patronising donnish tone he occasionally adopted that the capitals “stick out excessively far” (for what, one wonders?), that the Doom carving shows “how inferior (to what, Nick?) the aesthetic qualities of the sculptors were” and - unbearably snobbishly - “altogether uncouth, if thoroughly meaty, provincial work”. Provincial forsooth! Oh, no! Pevsner, whisper it, was an artistic snob who habitually overlooked artisanal carving altogether, to the great detriment of his otherwise indispensable “Buildings of England” series. I think it was a generational thing, Pevsner having died in 1967 and having spent a lifetime studying and teaching fine art at universities stuffed with classically educated public schoolboys. Simon Jenkins, whom I love to poke fun at, said “as flamboyant a show Tudor pomp as the tower at Layer Marney...” And he get the point as I do and as Pevsner did not that this monument is an important insight into both the Tudor and the pre-Reformation aristocratic mindsets. There’s not much more to say here; the pictures will speak for themselves. But do remember to walk around the outside of the east end of this church, notice all of the Babington iconography and reflect that what you are seeing, when you discount the modern nave, tower and so on, is to all intents and purposes what was once a standalone chantry chapel that has somehow survived those mad Tudors! |

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east. The Victorian nave replaces what was probably a very shallow predecessor for the use of the laity. The chancel arch looks to be original and of the thirteenth century in early English style. You can just about see the Babington monument at the right of the altar. Right: The view to the west end. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Left: Early English stiff leaf decoration on the chancel arch capita. Right: Early English triple sedilia on the north side of the chancel - a most unusual position. There are two little carved heads to be seen. Despite its EE look, I can’t help thinking this is either later than EE or that it has been moved. For a start, it is surprising to see seats for a full hand of clergy - Priest, Deacon and Sub-Deacon - in a Chapel of Ease which is what this building was at that time. Secondly, it seems an extraordinary coincidence that it is on the north side when the south side of the chancel - the normal place for sedilia - is totally occupied by the Babington monument. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

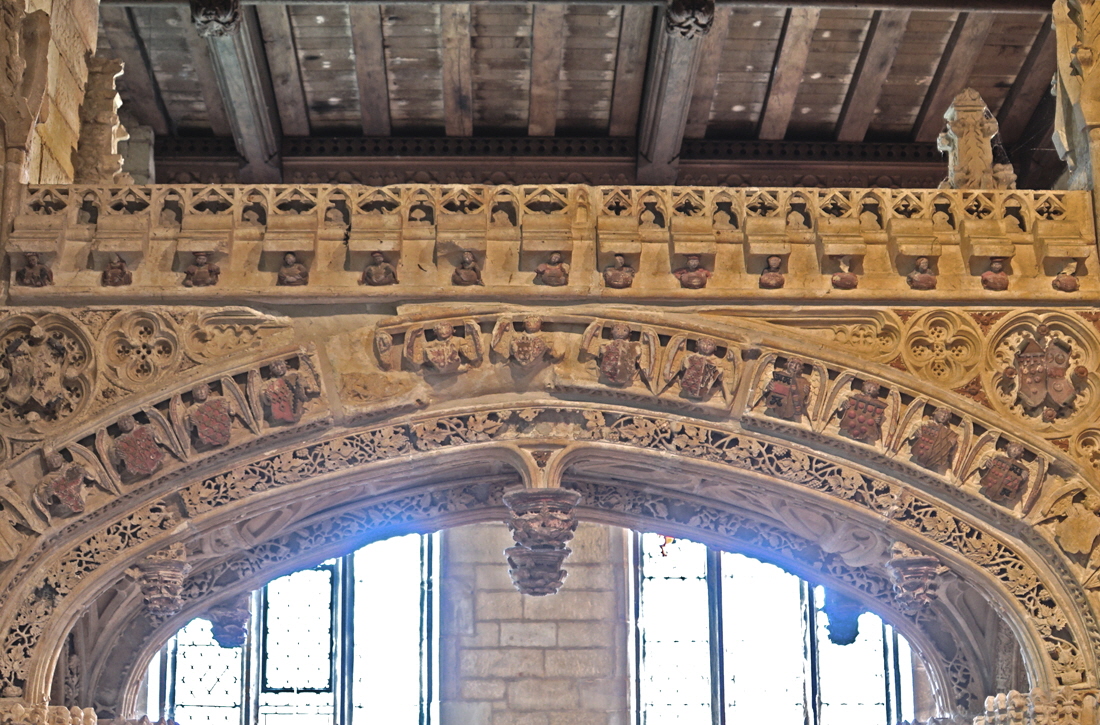

Although I over-use the word, I doubt anybody would take issue with my describing the Babington monument as “extraordinary”. There can be very few if any of its kind with its four big columns and its plethora of carved decoration, even down to the feet of the columns. The capitals on the columns are bedecked with groups of people clutching “tuns” or barrels. The arch has a course of fine interlace work. Outside that is a course of shields held by angels. The flattened archway to the left gives access to the altar from the chantry chapel in the foreground. More people with tuns are at the top of the monument and within the spandrels is stylised carving. Large decorated pendants are on the underside of the vaulted archway. Pinnacles have been placed at each of the four corners. Between the two right hand arches is a sculpted scene of what, as we shall see, is a portrayal of the Final Judgment. It is thought to have been the original chancel reredos moved here. The flattened archway to the left gives access to the chancel |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: A section of the south western capital. As on each side of each capital, the figures hold hands and link arms. The tun sculptures show the whole gamut of Tudor headwear. Right: Three figures from a section of the monument’s parapet. The woman on the right is wearing a gable headdress. These parapet figures clutch their barrels. |

|

|

|

Left: More barrel people. This group is particularly friendly. There is some damage to the undersides of the capitals as you can see clearly here. Right: A jolly little trio. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking through the two westernmost columns to a sculpted scene on the wall beyond. It was once over the arch of the monument but in the nineteenth century it was moved, probably because of worries about its weight. Right: Lovely deeply-undercut foliate decoration above the arch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The monument from the north side. The foliage and shield courses of decoration mimic those of the south. The shields are of real families with which the Babingtons had associations and from whom, no doubt, Sir Anthony hoped for Purgatory-shortening masses in his memory! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Babington monument from the chancel. Centre: The archway giving access to the chancel. It is topped with the family crest. Right: The east end of the monument with the doom sculpture set into the wall beyond. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Not least of the joys of the Babington monument are figures such as these carved into the lozenge-shaped insets to the columns. We must suppose that they depict real family members. Of course, many monuments had “weepers” - depictions of the deceased’s supposedly grief-stricken children, in postures of piety and humility. There is something much more real about these figures in their everyday costumes. We can only regret the defacement of some - were the people attainted? - and inexplicable weathering of others. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Coast of arms on the south arch of the monument. Right: One of the carved pendants below the arch. Sir Anthony was the MP for Nottingham in 1529 and 1536 when only the great and the good were members, He was also High Sherriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests from 1533-4. These posts would have been given only to men in royal favour and such people were only too anxious to ostentatiously show their allegiances at a time when you really did not want to cross Henry the Tyrant, as he should be known. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A section of the north arch. It us in rather better condition than the south. The coats of arms are richly painted. Right: The south side is a little less interesting. Angels hold blamk shields. The vine scroll foliage is pretty well the same as that on the north side but more damaged. And, of course, there are tons of tuns. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The western carved panel. Right: At the top of the western carved panel we see the arms of Henry VIII - rose and crown supported by greyhound and dragon. The Tudor rose is underneath. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Another play on the Babington name with chained baboons and babes standing on tuns. The baboons have speech banners. What are they saying? “You pull my tail, sonny, and I will tear your head off”? Right: Most of the column carvings are degraded, almost as if the monument has been outside. This is one of the better-preserved of the “dance of death” figures. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Although it as not originally part of the monument itself, this magnificent sculpture is one of its highlights. Fragmentary doom paintings chancel arches are always entertaining. although hardly rare. A doom sculpture is another matter. Obviously the canvas is smaller but all of the traditional elements are there On the left - it is always the left - the saved are being ushered into a turret, presumably the entrance to the City of God. To the right, half a dozen or so sinners are being consigned to the Jaws of Hell. Above that you can see people rising from their coffins. Christ sits above with attendant angels. There is a rather peculiar little column to the right and a space on the left where another would have been. Note the figures carved into the lozenge shaped recesses on the monument columns. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The saved heading for an eternity of talking to God, sitting on clouds, playing harps and watering pot plans (with acknowledgment to Edmund Blackadder). Centre: Blackadder suggested that Hell was a place for people who enjoyed the baser things of life (which I won’t enumerate here in this more sensitive age) but somehow I don’t think these poor buggers are going to have much fun at all as they enter the Jaws of Hell to the right. Note the tiny coffin above their heads with a groggy figure emerging to meet his Maker. Right: The strange column to the right of the sculpture. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The joyful saved and the not-so-joyful damned. Right: Jesus cuts a plump and avuncular figure with his acolytes surrounding him. Note the shawm player to the left. |

|

|||||||||||||

|

The east window recess of the chantry chapel is richly carved with arms and the single word “Deus” - God. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The east end is adorned with Babington family crests. That includes the east end of the original chancel (right) as well as the chantry chapel with its bay window. Right: The south side of the chantry chapel, also with family crests. |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: The Babingtons even managed to find a away to pit their arms in the chancel east window tracery. Right: The north side of the chancel also has Babington insignia, indicating it was part of the original chancel/chantry structure. It is all in great contrast to the military mundane nave and vestry. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Three pieces of sculpted decoration on the outside of the chantry chapel. Left and Centre: On the south side and badly weathered. Right: A beautifully carved design on the east end. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south. The rather vanilla Victorian church contrasts with the mediaeval chantry. Right: The village sign centres upon the church. |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |