|

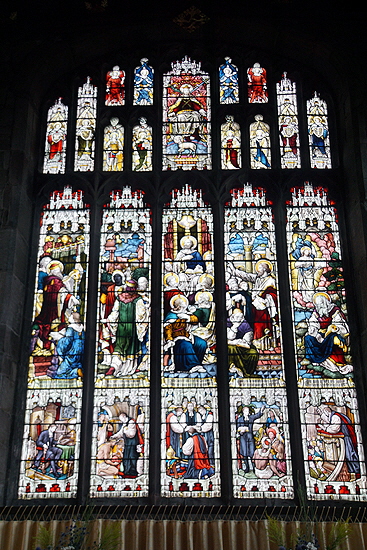

lower than they are today There was no clerestory, a somewhat ill-advised and cheeseparing omission. The church must have been very dark. We might tentatively venture that it also supports a pre-Plague building date since clerestories were all the rage in the suggested late fourteenth century. Whatever, it is unsurprising that in the fourteen eighties a major rebuilding took place where a tall clerestory was added, the aisles mush raised to their present height and the rooflines were made much shallower, necessitating the usual combination of waterproof leaded roofs, battlemented parapets to hide the ugly lead and gargoyles to drain water from behind the parapets. Nearly all of the windows were replaced and enlarged. Together with the clerestory this produced the much lighter church that we see todayThe chancel too was remodelled. It is incontrovertibly a fine building and to all intents and purposes a completely mediaeval one.

The interior has many delights. Most prominent are the Cholmondeley Chapel at the east end of the north aisle and the Brereton Chapel across the nave on the south side. Both, of course were Chantry chapels until the Reformation put an abrupt stop to the practice of chanting masses for the swifter release of the dead patrons from the horrors of purgatory. Both, however, remain enclosed by parclose screens and both sport impressive monuments. The Church Guides suggest that there weer as many as six altars in the church. of which four were chantries. Some of these may well have been maintained by religious or trade gilds. There is contemporary documentary evidence for the existence of a St Nicholas Chapel, probably on the north side. The Guide also avers that both of the surviving chantries were shortened to the west in 1717 when the rood screen was removed.

The chancel boasts a range of three stalls with misericords. One has the ubiquitous mermaid with mirror and comb. These are fifteenth century and it was recorded in the nineteenth century that there were twelve stalls here. Did the lost ones also have misericords? Malpas is one of only two parish churches in Cheshire with any misericords, the other being the twenty at Nantwich.

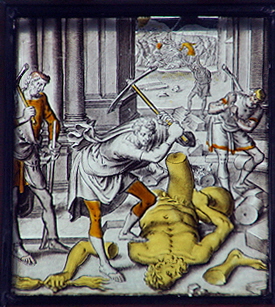

Another curiosity here is the great collection of Flemish glass roundels. Such roundels are surprisingly common in England - but they are never English! England did not produce “pot glass” - where pigments were fired “in the pot” during the manufacture of the glass. When Louis XIII of France went to war with Duke Charles IV of Lorraine in 1633 the Lorraine glass houses were destroyed, leading to almost two centuries in which hardly any pot glass was used in England. The roundels we see here are not of pot glass, but of glass colored with enamel paint that was made from melting ground-down coloured glass. It was painted directly onto clear (“white”) glass and then fired in a kiln. This removed the need for different pieces of coloured glass held together by lead in the traditional way. Presumably wealthy merchants were happy to buy these roundels for their local churches when they traded with the Low Countries to make up for the non-availability of traditional coloured glass. Whether they donated them or sold them, I do not know! It was a curious practice. The style is constant: very realistic paintings of complex and sometimes impenetrable biblical scenes with a penchant for lurid depictions of violent deaths and executions! I suppose they fitted in with the contemporary focus on scripture. Whether the scenes were ever decipherable by short-sighted English peasants and tradesman is somewhat doubtful and in those churches where (unlike at Malpas) words were inscribed, it was in Dutch! Which, I submit, would have been Double Dutch to most observers! Yes, I hear your groans.

|