|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

one. Beyond that Early English chancel arch a new chancel was built.Disappointingly, the stone screen which makes such a visual impact is Victorian by the ubiquitous G.E.Street as is the adjacent stone pulpit. Quite why such an anachronistic and somewhat overbearing feature was felt to be desirable is something of a mystery. It isn’t ugly but it certainly makes for an uneasily stark separation of nave from chancel. It is not that Victorian screens are uncommon: far from it. But the usual wooden structures are much less brutal visually. Above the screen is the beautiful and complete doom painting dating from the fifteenth century. This then must have been the easternmost extent of the fifteenth century nave because that is where such paintings were strategically located in order to scare the bejaysus out of the unwashed sinners of the parish. This means that the chancel had by this time been extended westwards into an area previously occupied by the nave, a most unusual alteration. Perhaps this coincided with the installation of the fourteenth century Decorated style east window we see today and which presumably replaced the usual Early English lancets. We can see that the area of the chancel beyond the old arch was very shallow and it seems that when it was deemed inadequate the decision was made to steal back some of the nave area rather than adopt the almost universal - and perhaps more expensive - expedient of expanding the building eastwards. Or perhaps the ground beyond the existing east wall was deemed unsuitable for further building? The lack of buttressing on this church, however, suggests that soil stability would not have been a problem so an economy measure is more likely. The architectural joys of this church, however, are not the nave or the chancel. In about 1440 an existing chapel north of the chancel was built by the Wilcote family as a chantry. Its quality is cathedral-like and its chief glory is its fan vaulted ceiling which is rare indeed in a parish church. It is believed that the chapel was built by the celebrated Richard Winchcombe who was active between about 1398-1440. Winchcombe worked extensively at the Oxford colleges and at several churches including Adderbury and Bloxham, also in Oxfordshire. Adderbury was owned by New College and Winchcombe rebuilt its chancel in Perpendicular style between 1408 and 1419. Winchcombe disappears from the records in about 1440 so the Wilcote Chantry may have been his final commission before death or retirement. Sir William Wilcote died in 1410 so the chantry was presumably commissioned by his widow, Elizabeth, who survived until 1445. Although their two alabaster effigies lie on a single chest, the figures were carved separately and Elizabeth presumably joined her husband upon her death. The east window of the chapel contains some mediaeval stained glass. There is another north chapel to the west of the Wilcote Chantry. In a curious twist, it was built for the Perrott family late in the seventeenth century and is in a neo-classical style. Its builder, Christopher Kempster had worked in London with Sir Christoper Wren. This too is a great rarity in an English parish church. and gives a curious “look” to the north side externally, juxtaposing Perpendicular and neo-classical architecture. Yet, somehow it works. The church is a most unusual mash-up of styles with much that is unusual. The doom painting and the Wilcote Chantry are the things that will linger longest in the memory. There is so much more to see here, however, and it is somewhat odd that it has passed so many writers by including, as usual, Simon Je...... Well you know who I mean. If this is not one of England’s 1000 best churches then I will eat my camera. Utter madness. Did he visit it? Really? |

|

|

I have seen lots of doom paintings but few make a visual impact like this one at North Leigh. In fact the whole of this view towards the east end makes you gasp. The doom sits above Street’s idiosyncratic stone screen. Above that you can see just a sliver of the beam of the original timber screen. Street’s complementary but somewhat lacklustre stone pulpit is to the right. Through the screen you can just see the responds of the thirteenth century chancel arch. You would not call the existing chancel particularly long and you can readily see why the church decided to move the screen west, grabbing chancel space at the expense of the nave, To the left you can see a glimpse of the fan vaulting of the Wilton Chantry chapel, the open niche of the Wilton monument visible just in front of the north side of the old chancel arch. The doorway to the right gives access to the organ chamber and vestry added in 1954. We must try to forgive those that commissioned that carbuncle. Photo: Bonnie Herrick |

|

|

Some things about the doom painting are unusual. It is missing the near-universal figure of Christ presiding over proceedings at the top of the painting. It is hard to know if a little of the scene has been lopped off at the top but its shape suggests otherwise. This means that the central area is filled by scenes of the dead rising from their coffins, which is more usually depicted at the bottom of the doom. Also unusual is the use of vertical decorative bands to split the painting into four panels. We will look in more detail at the painting further down the page. In the meantime, take a look at the more classical - and much more lavish - doom representation at St Thomas, Salisbury. |

|

|

|

Left: Looking east from the altar. The responds of the Early English chancel arch are to left and right. Also to the right is the open niche of the Wilton monument. Right: Looking from the west door. The arches of the south aisle have Norman capitals but pointed windows: a Transitional style. To the right, again, the Wilton chancel is just visible. In the background is the neo-classical Perrott Chapel of 1687 by Christopher Kempster. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: Looking into the Wilcote Chantry Chapel. It is a remarkably sophisticated Perpendicular style composition for an English parish church. Whilst it is true that some of England’s finest churches are built in this style - see, for example, Long Melford in Suffolk - in most churches it is represented mainly by post-Plague and pre-Reformation windows such as you see here but produced in quantity probably at the quarry. Fan vaulting, the glory of the Perpendicular style, is rarely seen.outside cathedrals and large town churches. (Photo: Bonnie Herrick). Right: The Wilcote monument rests beneath an ogee (that is to say S-shaped) arch. which is adorned with the usual twists and flourishes. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

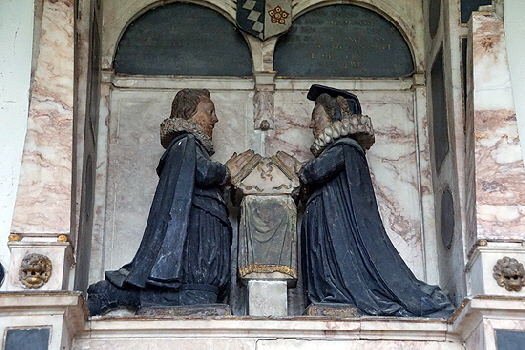

Left: The Wilcote monument. Note the incongruously plain and obviously disfigured chest with the alabaster effigies lying on top of it. These are surely not all of a piece and, oddly, Pevsner did not remark on this rather obvious fact. Right: The fine figures of the Wilcote couple. |

|

|

|

The Wilcote couple. Both faces are finely carved and Elizabeth was clearly a bit of a “looker”. Her headdress - see also below - is beautifully carved. Look also at the fineness of the carving of William’s chain mail and the pleats in Elizabeth’s dress. Even more interesting is the collar they each wear. It is the so-called “collar of esses”. Such collars were symbols of high office and particularly associated with adherents of the House of Lancaster - not necessarily, by the way, of military men. William was MP for Oxfordshire and Berkshire, a Privy Councilor and administered the estates of Anne of Bohemia who died in 1394. She was the first wife of Richard II who was himself deposed by Henry IV in 1399 and probably starved to death in Pontefract Castle in 1400. This was a man, highly valued by Henry, who would have warranted this badge of high office. It was quite customary to bequeath such a chain of office and it is fascinating to see Elizabeth depicted wearing it after her own death twenty six years and two husbands after William’s death! The esses collars were not all of standard design and you can see that the depictions here are absolutely identical so there can be little doubt. Both their sons predeceased Elizabeth and were themselves interred in North Leigh’s chapel. It seems certain that Elizabeth always intended to lie with them and her first husband. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The gorgeous carving of Elizabeth’s embroidered headdress. Note the image of a bird pecking at grapes. Right: At her feet, this dog is biting the folds of Elizabeth’s dress. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Left: Mediaeval glass fragments in the east window of the Wilcote Chapel, contemporary with the Perpendicular window itself. Right: A real curiosity, this. Above the screen on the chancel arch is a carved tympanum bearing what looks to be a coat of arms. Why it is here and when it was put here is anybody’s guess. It is NOT Norman, you can be assured! It doesn’t look as if it was made specifically for this space. Any ideas out there? |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The font is another curiosity. Pevsner was strangely silent about it which tells me he was baffled by it too. It is recorded that this is a mediaeval font that was consigned to the churchyard - the fate of many a font after the Reformation - and was brought back into the church in 1857 and “re-chiselled”. One can only presume it was a square Norman font originally, re-cut to vaguely resemble a Norman capital. and then mounted on an octagonal plinth that may or may not have borne the font it replaced. All very odd. Centre: The south aisle from the east,, showing its Transitional style arcade capitals. To the right is the two-bay neo-classical arcade giving onto the Perrott Chapel. Right: The Perrott arms in the spandrel of the chapel. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The monument to Robert Perrott (d.1605) and his wife. This is in the Wilcote Chapel. The Perrott Chapel was built much later. Centre: The east end of the south aisle, leading onto the vestry. Right: Pevsner cited the south doorway as being Norman and predating the Transitional architecture within. Was he right? I tend to think it was as a piece with the aisles. Within the old arch is another inserted during the fourteenth century. |

|

|

||||

|

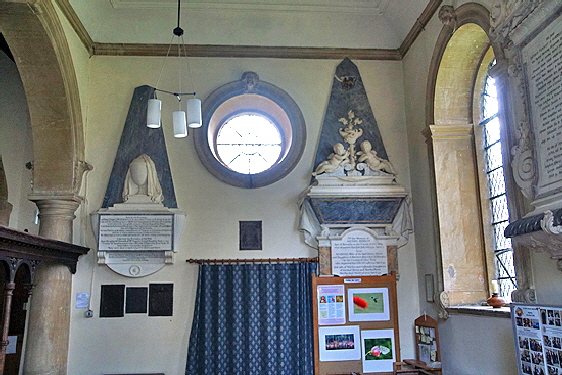

Left: The west end of the Perrott Chapel with wall monuments. Right; This being Oxfordshire, there are some super chest tombs. This one, complete with skull at its west end, took my eye. |

|||||

|

|

Doom paintings always have the Saved on the north side - that is, at God’s right hand as he stares out at you in majesty (although not here at North Leigh!). Not only is that side ot the painting usually much less entertaining that the Damned side with all its devils, pitchforks and jaws of hell but for reasons I can never fathom it is usually much more damaged; but not here at North Leigh. So here is a cheerful St Peter, key in hand, shaking hands with the new denizens of heaven. “Congratulations, my daughter. Glad you made it. Tea and biscuits inside”. Mary looks on, sizing them all up. The King and Queen have made the cut, as has a mitred bishop! They don’t always do so, as we shall see. Note the artist’s superb grasp of the human form. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now this is more like it! The devils are a real hoot. Most of the sinners seem to be women (the artist got THAT right!) and is it me or are the Jezebels that bit slimmer and more alluring than their heaven-bound counterparts? . Considering that the Jaws of Hell are nigh (bottom of picture) with a vile creature dragging them in, they look quite serene. At the back, though, you can see a crowned figure and also a Bishop in a black mitre (they are the ones you have to watch out for) who provide the customary salutary lesson that the rich and allegedly holy are not given Get out of Hell Free cards. St Michael looks on imperturbably, sword in hand. He’s seen it all before. His weighing of souls job is over for now. It’s a dirty job but somebody has to do it. See him at his work at Slapton in Bedfordshire. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The two centre panels are occupied by scenes of the dead rising from their coffins on the Dreadful Day of Judgement. Normally such scenes are shown at the bottom of the doom but this one, unusually, does not have a God sitting in judgement surrounded by sycophantic angels blowing horns, There is a preponderance of women here again. All look quite unperturbed. They have paid for daily masses for their immortal souls so every little thing is gonna be all right. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is an angel welcoming the Saved to Heaven. This is quite a trumpet! Photo: Bonnie Herrick |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Arms at the top of the Lenthall monument. Centre: The Tomb of the Unknown Skeleton. Right: This view of the west wall of the tower shows unmistakably the roofline of the Anglo-Saxon nave. Note its inordinate height: a characteristic of pre-Conquest naves. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Anglo-Saxon bell opening. Centre: Near the gable of the pre-Conquest roofline. You can clearly see the outlines of a window (at the top) and of a doorway. Right: The north face of the tower. You cans ee one of the pre-Conquest windows still extant as well as much later Gothic inserts lower down. |

|

|

|

Left: The outline of the original arch from nave to tower can clearly be seen here. It is of unusually large proportions. Taylor & Taylor dismiss the notion that is is too large for a pre-Conquest arch, citing the crudeness of the tiled voussoirs and the palpably pre-Norman imposts that can still be seen clearly set into the wall on either side. Right: The north side of the tower again, this time showing the Perott Chapel that was added in the later seventeenth century. It is a Marmite look: you can love it or hate it but it is a very unusual addition to a mediaeval church. For my part, it tickles my fancy to see two structures separated and yet joined by nearly seven hundred years of history. |

|

|

|

Left: The north east of the church, showing the Perrot Chapel this time juxtaposed with the Perpendicular architecture of the Wilcote Chapel. Is it so incongruous? Right: An angel, arms outspread, staring wonderingly at Elizabeth Wilcote’s head! She is surely thinking “where can I get a hat like that?” |

|

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

A .pdf Version of this page may be downloaded or printed below |