|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

a most remarkable survival. Of the church fabric there is little to be said and even Pevsner could not be asked to say much. Typically for this part of freestone-starved Norfolk, it is a flint faced structure and it is difficult to date. The windows are a hotchpotch in the high gothic styles. There is some flushwork along the bottoms of the walls. But you won’t be coming here for the building itself! |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Looking along the nave to the east and the magnificent rood screen. Note that the portions to left and right probably served sub-altars within the church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The northernmost group of dado panels served the St John the Baptist altar. From left to right: St Etheldreda, an Archbishop, St John the Baptist, St Barbara. Note the angels sitting above the main subjects. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The southernmost group of dado panel served the Lady Altar. From left to right: St Mary Salome, St Mary the Virgin, St Mary Cleophas, St Margaret of Antioch.. There is very much a theme of childbirth here. It is almost certain that a pregnant woman would have prayed here for a safe delivery of her child and would have returned at the time of her “churching” - her readmission to the church forty days after giving birth. It was a curious custom, inherited from the Jewish faith where a woman would need to be “purified” before readmission to the temple. In fact, there were explicit statements in the very widely-adopted liturgical rubric the Rite of Sarum that a woman was not barred from church after giving birth but, as was so often the case, local customs could differ. Possibly, the custom was adopted on the assumption that the Virgin Mary, as a Jew, would herself have undergone such purification after the birth of Jesus |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The panels in the main part of the screen, separating nave from chancel show the twelve apostles. The six panels on the north side shown here are, from left to right: SS Simon, Thomas, Bartholomew, James, Andrew and Peter. There are no angels above the panels of the main screen. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The six southern apostle panels. From left to right: SS Paul, John, Philip, James the Less, Jude, Matthew. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The side screen to the John the Baptist altar. The three figures are, from top right to bottom left: SS Felix (who brought Christianity to East Anglia), Stephen and George. Right: The side scree to the Lady Altar has: St Thomas a Becket, St Lawrence and the Archangel Michael. Becket’s image is a particularly lucky survivor of the Tudor period as Henry VIII wanted all images of Becket - who challenged the kingly authority of Henry II - expunged. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail of Archangel Michael. Right: Although the panels themselves are rightly the centre of any visitor’s attention, this picture attempts to capture the richness of the peripheral decoration on the timber uprights and the coved loft above. St Thomas a Becket is the saint in the picture. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: St George stands serenely, sword upraised, over a rather weedy dragon. It hardly looked like a fair fight to me. Centre: Detail of one of the gilded sidescreens. Right: Detail of a painted upright. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

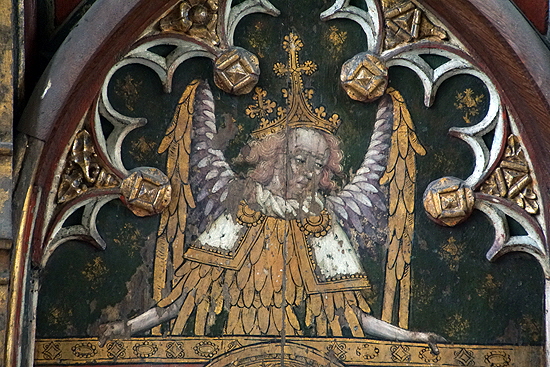

Left: Each of the saints depicted on the St John the Baptist and Lady Chapel screens is surmounted by an angel. This one looks like another depiction of Archangel Michael.. Right: The head of St Barbara. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail of the panel depicting an unidentified bishop. Right: Detail of one of the side screens. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Gilded detail. Note the fineness of the carving. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Detail of the rood screen as seen from the eastern side |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The screen from the east. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Cantor’s Stand: an extraordinary survival in a parish church. Pevsner believed it had been used from atop the rood screen before its superstructure was removed at the Reformation. Centre: The chunky font of indeterminate vintage. Right: The corner piscina with ogee decoration in the perpendicular style. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

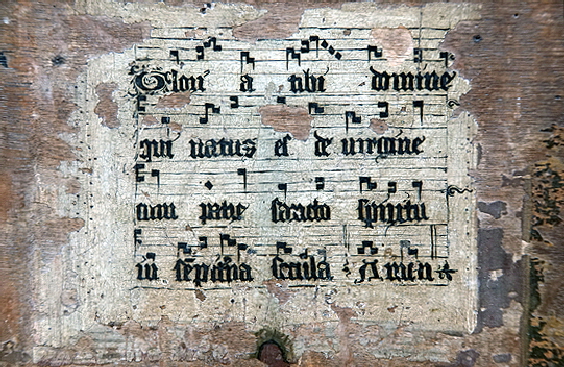

Left: The music for “The Gloria” painted above the cantor’s stand. Right: Whilst on the other side is the eagle of St John with the opening line of his gospel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are six misericords here, in two groups of three facing the altar on the east side of the rood screen. When G.L.Remnant wrote his definitive and indispensable book “A Catalogue of Misericords in Great Britain” in 1969 (hard to find, even second-hand and decidedly not cheap), he reported six stalls but only four misericords. Since then two “new” misericords have been added in 1998, seemingly mounted on original mediaeval timber seats. Unusually, these are tastefully done and more striking than their mediaeval counterparts. Remnant dates the original four to the fifteenth century. Left: The most interesting one: A man with his hand on his knee and the other on his waist . Right: A man with pointy ears. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A squashed little face. The supporters are much more interesting. On the right is a six pointed star - a “hexagram” - with a small rose at its centre. That little quirk perhaps suggests that this is not just a carpenter trying his hand at geometric carving. The hexagram has been used since the earliest days of Christianity as the “Star of Creation”, the world having been created in six days. Its origins are not in Judaism but go back at least to the Egyptian civilisation, I believe that on this misericord the rose is meant to represent the Virgin Mary - often represented by a flower - within the Star of Creation. The left hand supporter is even more interesting, at least to me! This is a circle interlaced with arcs. I have written extensively about this iconography and searched for it in English churches, following the revelation by the late Mart Curtis Webb that it represents Plato’s “Cosmic Harmony” and was used throughout Europe in many Christian settings. See “The late Mary Curtis Webb” on this site. Most, although by no means all, appearances of this symbol in England are on Norman fonts. Many are earlier than Norman and I have seen it in a fifth century church in Ravenna. This misericord is a couple of centuries later than Norman which casts doubt on whether it was symbolic rather than the carpenter copying a design seen elsewhere or even thinking he was doing something original. On the other hand, if the other supporter is symbolic then just possibly this one is too, Right: Plain vaulting with a tracery pattern similar to that on the other misericord shown here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now for the two modern misericords. Left: Anyone who has cruised on the Broadland rivers will instantly recognise this as a representation of the ruined St Benet’s Abbey nearby. Indeed, the (rather anorexic) Church Guide suggests that the four mediaeval misericords came from there when it was closed at the reformation. As supporters we have bishops mitres and a crook, presumably in homage to nearby Norwich Cathedral and to curry favour with the Bish! Right: I think this is meant to be the prow of a boat on the nearby rivers and Broads. The supporter to the left is a Swallowtail Butterfly - one of England’s rarest and found only in Norfolk. On the right is a dragonfly, also found all over the local waterways. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Supporters on the modern misericords. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top Two Pictures and Bottom Left: Images on the armrests of the mediaeval; stalls. Right: The southern misericord range. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Two surviving mediaeval poppy heads with grotesque faces. Right: The Archangel Michael. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: After the glories of the rood screen and the misericords, the western aspect of the church is somewhat overshadowed. Note, however, the tower arch. If I have seen one of taller proportions I can’t think of it. Centre: The south door. Right: The Virgin in a Perpendicular style niche above the south door. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Painting on the underside of the rood screen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. Right: The church from the north west. Unusually, the porch has a room (a “parvise”) over it. In rural English churches this was far more likely to be over the south door but it looks as if at Ranworth this was originally the main entrance. That too is fairly uncommon to be the “Devil’s Side” through which many preferred not to enter. See Church Hanborough for more on this, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

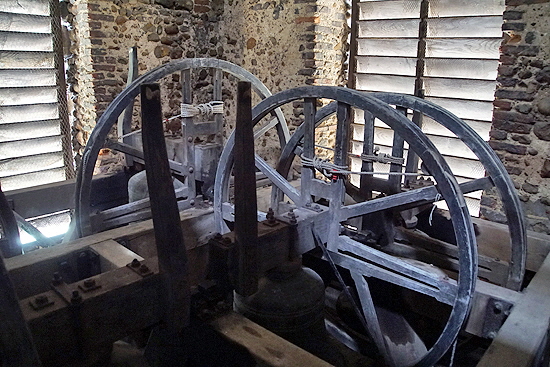

Left: The weather vane dates from 2010 and the story behind it is charming. I quote from the church’s own website: “The Pacificus wind vane, which was erected in 2010, replaced the crown wind vane that had been in place since 1953 in honour of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Based on local legend, Pacificus was a devoted monk at St Benet's Abbey in the 15th century, who came to Ranworth Church everyday with his dog, Caesar, to restore the rood screen. His devotion to the abbey was tested when one day he was rowing back from Ranworth only to see St Benet's ablaze and plundered. Whilst all of the other monks fled to seek refuge in monasteries overseas, Pacificus could not bring himself to leave the place he loved so much. He remained at St Benet's abbey, continuing his work on the Ranworth rood screen, until his death, upon which he was buried in the church yard.” It’s a great story, isn’t it? But - er - St Benet’s Abbey was “ablaze and plundered”? In the fifteenth century? By whom, one wonders? Three centuries too late for Vikings! One wonders what torments earthly and heavenly would have fallen to such raiders. Where’s that salt cellar? Good story though and it is genuinely heartwarming to see church’s still cleaving to their historical traditions in this way. Churches continue to be repositories for our local history: just think of the many USAF stained glass windows in East Anglia and the innumerable “Millennium Tapestries” everywhere. Long may it continue. Right: Dizzyingly - literally and metaphorically - you can ascend the stone spiral tower stair here in blatant disregard of the law that nobody must allow anybody else the opportunity to kill or main themselves despite their very best efforts because it would be all your fault. Bravo, Brave Little Ranworth. Here we see bell mechanisms on the way up. My fellow church crawling fanatic and photographer extraordinaire, Bonnie Herrick, rings the bells in the finest Anglo-Saxon tower in England at Earls Barton in Northamptonshire. And I really do try not to hate her for that privileged access. Not always successfully. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two views from the top of Ranworth Tower looking over the flat and soggy landscape of Broadland. The channel down which boats must come from the River Bure to access Malthouse Broad is very obvious. The unnavigable Ranworth Broad is to the left of the channel, Malthouse Broad to the right |

|

|

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

You may Print or Download a copy of this page through the .pdf file below |