|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

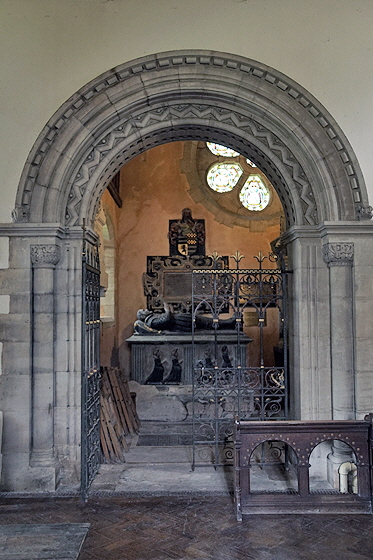

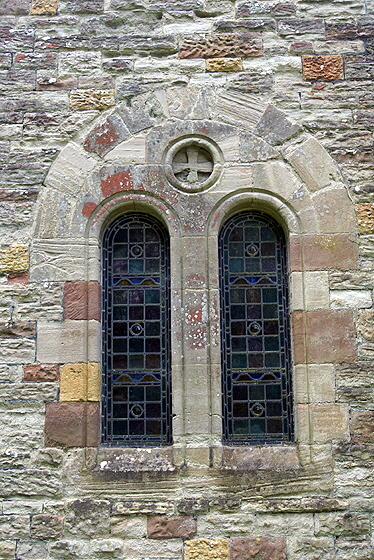

houses a range of monuments to the Rous family. Access is via a hefty neo-Norman archway with capitals which, if you did not know better, could be original. The east end of the north aisle contains an eyebrow-raising, incongruous but rather beguiling Italianate altar canopy. The chapel is apsidal yet the surrounding exterior is square. So even the apse is a pastiche. If you are here hoping for a Romanesque church this architectural aberration will have you tearing your hair out! If so, you will be missing the point: everything about this church is a bit of a hotchpotch but is is never dull. In fact, it is one of the most entertaining parish churches I have ever been to and that south door and sculpture pay for all. Preedy did not stop at the interior. That north chapel has a rose window and a decent if doomed attempt at a Norman corbel table. In fact the north aspect, in stark contrast to its simple south side is a remarkable jumble of excrescences with gabled roofs and there is even even a chimney! In true Rous Lench style, all of this whimsy is counterbalanced by a late Norman north door. Other treasures include Elizabethan (not Jacobean) pulpits and lovely ironwork on its two doors. Doubtless, the latter are also Victorian but they have a lovely Anglo-Scandinavian feel to them. Then there is a roomful of monuments, of which much more anon. This is one of the most entertaining churches you will visit. Jenkins excludes it from his 1000 best. Don’t let that bother you. This church is fun throughout and I guarantee you will enjoy it. And if you don’t think that Norman sculpture alone is worth the visit then you are reading the wrong website! |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The gorgeous composition of Norman south door and sculpture. The jambs and the barley sugar twist collonettes may well have had attention from Preedy. There was surely a carved tympanum originally. The outer course of zig zag moulding is damaged. Centre: Christ within a mandorla with hand raised in benediction. It is intricately carved and it is truly remarkable how clear and crisp it looks after nine centuries and more. Either side are decorative collonettes. The zig zag moulding of the arch has been badly repaired at some point. This is a true treasure. Knowing that it still sits outside open to the vagaries of the weather and pollution is sobering. Right: The bellcote. I swear that it took me some minutes to be finally certain that this is not original Norman. It is those dinky little flower carvings and the ends of the hood mould that give the game away. That is Victorian prettiness, not Norman vigour. Preedy put it here. There is but a single bell. It replaced a wooden structure which housed two hefty bells which are on display on the floor of the north aisle. One can well imagine that it needed replacing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The two collonettes of the sculpture niche are heavily decorated. This, the right hand one, has a cat mask with tendrils spewing from its mouth and seemingly forming a small tree. There is fruit and possibly, just below the face, an acorn. Centre: It is difficult to discern what this left hand collonette is representing. Right: The south doorway. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The south door capitals. Like the sculpture, they have survived the centuries remarkably well. Left: A cat mask on the outer face of the right hand capital. Right: The full capital, showing the foliate inner face and the cat mask. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The two faces of the left hand capital of the south doorway. Right: The top of the south doorway. Note the damaged outer course of zig zag moulding. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The church looking to the east. The chancel arch is original Norman work. The screen is from the nineteenth century restoration. To the left, you can see that the altar, surmounted by its ciborium, matches the main altar albeit on a smaller scale. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The screen. It is noticeably fine and flimsy but rather pretty. “Screen” is perhaps to overstate things. Right: The chancel. There is no real indicator of the fact that it dates from the thirteenth century. The exposed stone is clearly different from that employed in the nave. The scraping of the east and south walls, often an aesthetic disaster, forms a quite pleasant contrast with the bright north wall and the neat little altar and reredos. It shouldn’t “work”; but somehow it does. The ”Y” traceried east window - an early Decorated style trope - is a replacement. For some unfathomable reason Preedy relocated the original window with plate tracery at the west end of the north aisle. It could be that he felt it as over-large for what is now a rather cosy little space. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking west down the north aisle. To the left are Norman columns. To the right you can just make out Preedy’s neo-Norman doorway to the Rous Chapel. At the west end the plain octagonal font looks a little overshadowed by the somewhat incongruously elaborate font cover that requires a pulley to raise and lower it. Centre: The entrance to the Rouse Chapel in neo-Norman style. Right: The curious arrangement at the east end of the north aisle. Preedy has installed another “Norman” arch, very much in the style of the arches of the genuinely Norman arcade. Beyond it is the anachronistic apse set within an externally rectangular building. The altar is surmounted by a “ciborium”. It is self-consciously Italianate and imitates, it is said, a similar structure in St Marks in Venice instigated by one Rev Dr W Chafy who in 1976 bought Rous Lench Court from the Rous family. I hope you are getting a feel for how much fun this church is! Bonkers, in fact. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The altar under its ciborium with the pretty barley sugar twist columns. It is blatantly Roman Catholic in style. Did Dr Chafy adhere to the Anglo-Catholic Oxford Movement? Of all the incongruities in this church, this one takes the palm. The framed religious photographs add to a bizarre look. The arches are rounded and, in truth, the top of this structure with its little blue dots is a bit lame. Yet it is supported on rather well carved Norman-style capitals that look remarkably like the real thing. Not only is this structure incongruous within the overall structure of what was, after all, originally a real Norman church but it also manages to have incongruities of its own! Right: Looking through the Norman north arcade to the south west corner of the church. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: The two original bells that were supported by a wooden bell cote! They were both cast by John Martin of Worcester. The treble bell (left) is dated 1611. The other bell has the inscription “God be our Speed” (right upper) and the “JM” mark of its manufacturer (right lower). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These two capitals adorn Preedy’s arch through to the Rous Chapel. They have been carved with astonishing authenticity. I would defy anyone to see them as Victorian without pre-knowledge. There is not an element of the designs that you would not see on a genuine Norman capital. Whoever carved these had knowledge of the original forms and did not care to make them more “contemporary”, amost refreshing approach for a Victorian. The masks, the whorls, the pellet mouldings are all pure Norman forms. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the ciborium capitals. Again, with its foliated cat mask, it is an extremely good attempt at Norman design. Note also the double billet moulding above it - another Norman form. Right: The west end of the nave. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The monument to Edward Rous (d.1611) and wife Mary Haselrigg (d.1580). They have four weepers: not very many for that time. Centre: Recumbent Edward Rous. He has his feet on the head of (probably) a Turk or a Moor. This martial reference, however, is not born out by his costume which is that of an Elizabethan gentleman without armour, possibly because he was never knighted. I am always a little bemused by these not infrequent nods to the struggle between Christianity and eastern infidels half a millennium after the crusades. By this time Christianity’s travails had a great deal more to do with European politics and doctrinal issues. Right: This late seventeenth century monument shows how far both the architecture and characterisation of death came over the course of a century or two. Edward Rous’s Elizabethan tomb shows both husband and wife in the usual attitude of prayer and piety surrounded by their praying children. It is an attitude of “We love our God and hope we will be joining you in heaven”! Not long before this era there was an attitude of resignation with an emphasis of the corruption of the body (as seen in many so called “transi tombs”, the inevitability of death for rich and poor and the judgment to come. This seventeenth century monument, however, has a sentimental feel to it. Death looks almost dreamy. Cherubs fly around (as they do) and a heartbroken woman sits there mourning her noble and illustrious hubby with all his curls and distinguished looks. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Edward Rous monument. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This particular branch of the Rous family (there are several and they seem to have their origins at the time of the Conquest) does not appear particularly interesting so I am not going to discuss the other monuments and wall slabs here. It is interesting, however, to see the Rous family arms represented conspicuously above each of them except the seventeenth century one. More about that below! Left: The north wall. Right: The east wall. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ok, so now to the mystery. We have already seen Edward Rous with a Turkish or Moorish head crushed beneath his boots. Nothing unique about that. But who does the Rous arms in this church have a similar face above all of the manifestations of the family arms? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The moorish head beneath Edward’s boots. Second Left: The same moor appears on the arms above Edward’s monument. Second Right: Here’s another. And - get this - he is wearing a crown! And - get this - it has a cross above it. It looks like part of our own Crown Jewels. Right: Here’s another. This time he has no crown but he does have a cross. And his headgear is very like that of the moor beneath Edward’s boots.There are at least two more around the chapel. Is there any rational explanation? None of the modern Rous arms I have seen feature such a thing - unsurprisingly. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Something well worth looking out for, but frequently overlooked, is the ironwork on mediaeval doors. These examples at Rous Lench (the bottom right on the north door, all of the others from the south) are surely Victorian. Look, however, at how again the restorers have stayed true to the church’s origins. These all have an Anglo-Scandinavian feel to them. Look in particular at the dragon’s head (top right). And they are all well done. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The very peculiar-looking north side. Let’s begin by saying that this is a church whose north side is not unloved or unkempt. But this a very odd configuration. The bell cote marks the original part of the church with the rooflines of nave and chancel just about visible. The north side of the nave is almost hidden between the north aisle and the chunky Rous Chapel on the right here. It has a chimney of all things. Then we have an “inner vestry” and an “outer vestry” and lord knows what else so what was a very modestly proportioned Romanesque two-celled church now has seven cells! If you compare this to the simplicity of the southern aspect the contrast is quite startling. Right: The neo-Norman Rous chapel is in the foreground with neo-Norman blind arcading and a rose window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Preedy even built a faux-Norman corbel table on the west side of the Rouse Chapel. Wisely, in my view, he did not attempt the impossible and make it authentic. In reality they are not even corbels - they do not help to support the roof - but he showed respect for the Norman building traditions. Most of the designs do nod towards “real” Norman themes. Right: The rose window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Faux Norman windows on the vestry. Centre: Allegedly authentic Norman doorway on the north aisle. Just how authentic is questionable. It would have been built into the nave wall when the church was built and then moved to the north aisle when it was added. But, as we have seen, the north aisle was demolished at some point. The barley sugar twist collonettes match those on the south side and are surely Preedy replacements. It does look like a Preedy piece overall. Right: The Elizabethan pulpit. |

|

|

|

Left: The east end. Right: The west end. Note the north aisle window with very early Decorated style plate tracery (that is, with “tracery” formed by cutting a pattern directly through the stone). It was originally the east window. |

|

|

||||

|

Two more views of the south side. |

|||||

|

And finally....expanded views of two of the great treasures of this intriguing and entertaining church, separated by eight hundred years of history.. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |