|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

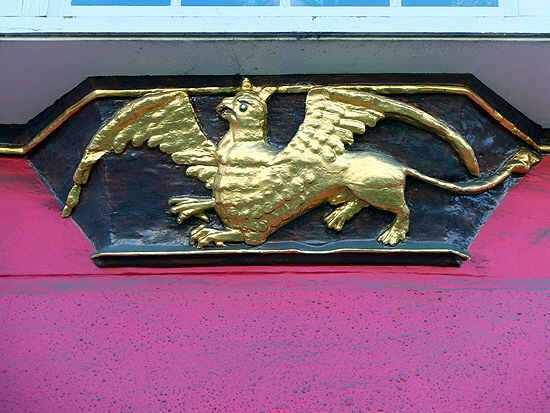

for several year, if not for decades, by the carnage of the Great Plague of 1348-50 and other only slightly less disastrous outbreaks in the later decades of that century. Essex being well within purlieu of London, any reputable surviving masons were likely to have been pressed into serving the King’s great works. The architecture here, then, is very much of the Perpendicular style that became the norm after the cataclysm. Work carried on until just before the Reformation. As with so many churches in prosperous towns, the growing merchant class just couldn’t stop demonstrating its prosperity through its church in a mad game of “Outdo my Neighbour”. What they left was a church that was more or less a rectangle in plan with a west tower. The chancel was rebuilt just before the Reformation with chapels to north and south The transepts had been overwhelmed to the status of mere excrescences. It became, in short, a great big prayer barn of a place. And it is very, very white! Dulux might be a sponsor. Or Persil. What redeems the church for those not easily seduced by magnificence is its gallery of carvings in wood and stone. The real treasures are the bottom parts (sounds rude, doesn’t) it of ancient rood screens. Both here and in Suffolk there is a tradition of carving all sorts of beasties in the spaces between the caved arches and the rectangular framework. And Thaxted’s might well be the best of the lot. Note about the photographs. I visited this church with my good friend Bonnie Herrick. She arrived long before me to use her tripod and slow shutter speeds to get the wonderfully well-focused pictures she craves before her slapdash friend arrived. As usual, though, this meant she took one picture for every ten I took. Then I found she had been here before on a really fine day in 2018 - before I knew her - and had spent hours here, as is her wont. I won’t look a gift horse in the mouth so I have availed myself of her pictures, especially outside the church. These are marked “BH”, |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking east towards the chancel. The arcades are identical in style. Centre: The south chapel. As with the north chapel and, indeed, the chancel itself. the windows are huge, rectangular to the side and with a flattened arch to the east. They all dated to just before the Reformation and reflect the Tudor eras of Perpendicular architecture. Right: The north chapel. The chapels are as identical in style as are the two arcades. But the tiled floors are different! |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end. Centre: Looking up the north aisle. Right: Looking down the north aisle towards the west window. Note the font with its ornate wooden cover. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking to the west end of the south aisle with its huge Perpendicular style window, almost identical to that of the north side. Right: (BH) Another view to the east. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Unless it was out of stock, the church lacks a comprehensive Guide Book, although it has a veritable cornucopia of focused monographs and little leaflets. None of them mention this delightful preserved section of mediaeval screen. This is on the north side; there is another on the south side. Although much restored, they are fifteenth century. The delight is in the carvings in the spaces between the arches and their rectangular settings. As in many Essex and Suffolk churches, they have been filled with with monsters and grotesques and they are amongst the very best. On the south side the grotesques are sited within the arch itself. They are strangely overlooked in accounts of this church. Remember where you heard of them first. Right: On of the panels where you can clearly see the beasties in the upper corners. |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

All photographs above are of the screen carvings. Some are obviously lions, pelicans and so on but most are fantastical. Note the different locations for the carvings between the north and south sides. Right: Hanging in the south aisle How nice is this? It was painted by the Marquis d’ Oisy - see below. |

|

|

|

|

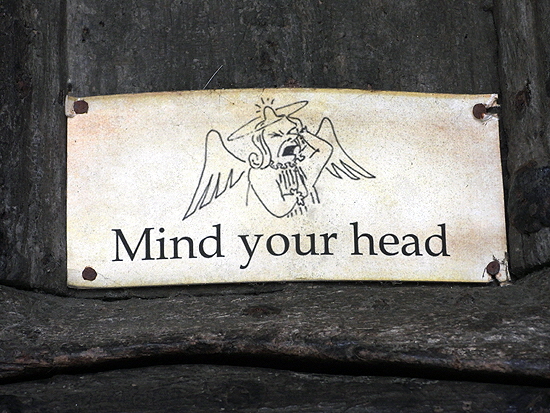

Left: On a foul day in January 2022, this is the magnificent north porch. I have remarked elsewhere that you are much more likely to find a north door being used as a main entrance in a town church than in a village church. My theory is that the town churches has more sophisticated priests and congregations who were more sceptical about the old trope about the north being the “Devil’s Side”. This is a fine entrance to any church with its arms, niches and (at the top) a frieze. The south porch is fourteenth century, smaller and less ornate. It seems that it was superseded as the main entrance, reflecting a change in the town’s commercial centre of gravity. Centre (BH): The north doorway. It has a lierne vault - a most unusual and expensive feature for a parish church - with bosses. It is mid-fifteenth century. Right: The west tower entrance. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

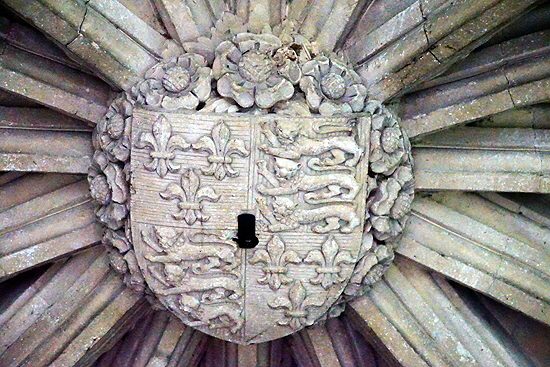

Left (BH): The arms of King Henry VI and Edward IV adorn the south porch. These two protagonists on the Wars of the Roses had the same royal arms.The porch pre-dates the Wars of he Roses. Edward was a patron of the church so these arms surely are meant to be his. Right: Edward’s arms are also on the central boss the vaulted ceiling. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Upper (BH): The north porch vault with the royal arms at its a centre. One can only presume that the other heraldic shields are of other local patrons and bigwigs. Right Upper and Lower: More porch bosses. The upper one denotes the Bourchier family - see more below. What does “Wis Gar” mean? Left Lower: Taken in atrocious light, this is the vault of the south porch to compare with that of the north. It is nice enough but much less grand than the north and with no liernes (ribs that join neither the sides nor the centre of the vault |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four Pictures Above: All of these were taken by Bonnie Herrick with her Nikon P1000 camera, not altogether inaccurately described by one reviewer as a massive zoom lens (3000mm maximum focal length!) with a camera attached. A tripod is, as you might imagine essential! They are all wooden bosses from the south aisle ceiling. Top Left: One of the church’s monographs suggests that this is a pomegranate “dimidated” with a bunch of grapes. There’s another wonderfully arcane word to get your friends rolling their eyes at your anorak-hood. (No, dunderheads - anorak-hood, not anorak hood!). It just means the merging together of two coats of arms or heraldic devices. The monograph suggest also a connection with Katherine of Aragon, of whom the pomegranate was a symbol, and this would accord with a putative sixteenth century date for the ceiling. Top Right: The “Bourchier Knot”, the symbol of the Bourchier family of, amongst other places. nearby Stansted Hall. Henry Bourchier, a great grandson of Edward III, became the Earl of Essex in 1461. The Bourchier family were the fifth holders of this title, and on the death of this Henry the title was inherited by his son, also Henry, who died in 1540 after which it lapsed until granted to the Devereux family in 1572. This boss must represent him rather than his father if the church is right in suggesting Katherine of Aragon is denoted by the pomegranate boss. Bottom Left: Three bugles. I believe this was a crest of the Smith family of Thaxted. Bottom Right: A rate appearance in English heraldry of three shamrocks. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left (BH): Two bougets (“budgets” or water carriers) on a carrying yoke. This is probably another Bourchier symbol. Sir John Bourchier (d.1474). He was a Knight of the Garter, flourishing under Edward IV. His garter stall symbol was a water-boucher. Important mediaeval families were quite happy to make plays upon their own family names and it is less surprising than you might think. “Bourchier” probably derives from the French “Bouchier” or butcher or, possibly from “Bourgier” - keeper of the purse. The family name first appears on the fourteenth century - in Essex - but their ancestors arrive with the Conqueror. Centre Above and Below: Two more family crests in the nave, one being a recurrence of the three buglehorns. Right: This is not a church with sets of interesting choir stalls or benches but at he top of this one is a nicely-carved hour glass, perhaps reminding us all of the inexorable passage of time. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left (BH): The font has this rather grand case and cover of the fifteenth century Centre: The font cover with its splendid Perpendicular style carving and cusping. Right: A section of the aisle ceiling; |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left (BH): This cross beam is at the junction of the south transept and the nave. Two splendidly elegant serpents or dragons tuck into some foliage. This is quite a common piece of imagery and you can see many examples on the wall plates in Burwell, Cambridgeshire. Right (BH): There are some wonderfully ferocious wooden corbels on the south side |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two more wooden carving - both pictures by Bonnie Herrick. Left: This demonic creature has a chain of office around his neck. Right: And you thought Mad Cow Disease was a recent thing? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More pictures from Bonnie Herrick and her all-seeing lens monster lens. Left: Even I (a sceptic about these things) think this might depict a real person. Centre: But I don’t think this one does! Right: A very interesting boss. Ringlet-bearded men are to left and right. I have a theory that this is the traditional depiction of the martyred St Edmund in Essex and Suffolk, as such representations are ubiquitous and he was, of course, a Suffolk man. To top and bottom are clean-shaven men or women. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Glass in the south aisle by the renowned (and prolific) Kempe who died the same year - 1907. It is interesting for it the figures depicted: Edward IV, “Prior of Stoke-by-Clare”, “Thomas, First Vicar of Thaxted”, and Gilbert de Clare. Clare and Stoke-by-Clare are about fifteen miles away in adjoining Suffolk. The so-called “Honour of Clare”, first bestowed by the Conqueror on Richard FitzGilbert included the manor of Thaxted, hence the associations. Right: Restored mediaeval class showing poor old Adam and Eve. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: Two panels from the Victorian glass. Neither figure, I have to say, looks remotely like his photographs! Second Right: A sixteenth century stained glass window depicting a saint. Right: This knight found in the transept is dated from 1341 and probably depicts Edmund, Earl of March who held the manor at that time. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A very peculiar capital. The white paint here does nothing for the stone carvings inside the church. This looks like St Catherine with a couple of undersized wheels. Right: An unusual corbel. Perhaps the Coronation of the Virgin? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are a variety of “angels” in side the church. Many are routine depictions of angels bearing shields (I wonder why that do that? Just askin’). Others are praying which is what angels do a lot of apparently. But these two (both pictures by Bonnie Herrick) don’t have wings and hold books. The Church Guide calls them angels with books but observes that hey have no wings. Sorry, guys, but that it pretty clearly because they are NOT angels, right? They wear cloaks! With their cute hairstyles they re unlikely to be monks. So perhaps they are clergy? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This chest at the west end of the church is easily overlooked. It is modern and seemingly uninteresting - unless you look closely. In the picture right you can see a hammer and sickle image sitting above and presumably symbolically crushing a crown and two bishops’ mitres below. The right hand panel shows an idyllic scene of cello and violin players. Thaxted Church was embroiled in what we would today call “Culture Wars”. Its vicar from 1911-42 was Conrad le Despenser Roden Noel; a good proletarian name if ever there was one. He was one of many silly old sods in the England of that era and later who saw Stalin and his mates as holding all the answers to England’s poverty and inequalities. You might enjoy reading about it here. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The second panel. I’m less sure of what these mean. On the left a clergyman leans from his pulpit and reaches out to two figures below. It’s odd to see left wing imagery within a Christian context, Stalin having of course suppressed the Church in Russia for decades. And in the panel above the Church, or at least the bishops, is seen being crushed by the hammer and sickle. The usual contradictions found in the thinking of extremists of all colours, perhaps That said, I don’t know who carved this and how it comes to be in the church. Right (BH): Grotesques howl from one of the pinnacles. |

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: As with the “red chest” above, I think that it is necessary to celebrate the good things in our churches, no matter what the vintage. The “red chest”, for example, show that history is still being reflected in our parish churches and this is to everyone’s advantage, not least the future church crawler and historian, providing Woeful Welby has not succeeded in closing them all down. This picture shows the lovely eagle lectern. It was painted by the Marquis d’Oisy, commissioned by Conrad Noel (see above). D’Oisyi, in fact, was not of aristocratic birth, was born Ambrose Merchant, son of a gasfitter in Bath. In England! Centre (BH): Western entrance to the north porch with an unglazed Perpendicular style window beyond |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. Centre: The north transept was built in around 1400 at a time when external carving was becoming riotous. Here we have a label stop caring of a woodwose - the old man of the woods. They are ubiquitous in Essex and Suffolk and not uncommon in other eastern counties. They undoubtedly had pagan origins. But these are not benign images. The woodwose carried a club and would, it was said, abduct women and eat unbaptised children. There is a true story that in 1392 King Charles VI of France and five other nobles dressed as wild me for a court festival. Their costumes were made of pitch and flax. The five nobles were chained together, but not the King. Someone took a flaming torch too close to the nobles. Four of the five nobles were burned to death. So don’t try it at home! Interestingly, by the way, the surname “Woodhouse” derives from Wodewose. I bet Jane Austen didn’t know that when she named one of her heroines Emma Woodhouse! Right: This also looks like a woodwose, this time playing a harp! All three photographs by Bonnie Herrick. |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel. Centre: The north transept was built in around 1400 at a time when external carving was becoming riotous. Here we have a label stop caring of a woodwose - the old man of the woods. They are ubiquitous in Essex and Suffolk and not uncommon in other eastern counties. They undoubtedly had pagan origins. But these are not benign images. The woodwose carried a club and would, it was said, abduct women and eat unbaptised children. There is a true story that in 1392 King Charles VI of France and five other nobles dressed as wild me for a court festival. Their costumes were made of pitch and flax. The five nobles were chained together, but not the King. Someone took a flaming torch too close to the nobles. Four of the five nobles were burned to death. So don’t try it at home! Interestingly, by the way, the surname “Woodhouse” derives from Wodewose. I bet Jane Austen didn’t know that when she named one of her heroines Emma Woodhouse! Right: This also looks like a woodwose, this time playing a harp! All three photographs by Bonnie Herrick. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bonnie Herrick’s Thaxted Gallery |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bonnie was born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio but the moved here in her twenties just because she wanted to live in England. I still half expect to find she held up a bank but she is adamant it was a lifestyle choice. She has been here ever since and has never lost her enchantment with the built heritage of the country. She still stares in wonder (“Holy Cow, Lionel!”) at the buildings which so many English people take for granted as she happily perambulates around in her little car nowadays focusing on churches but still drinking in everything she sees and making friends everywhere she goes. She still sounds as American as Pecan Pie and that opens many doors for her, literally and metaphorically. If she is in your car you have to get used to stopping the car (“oh baby, baby, baby!”) for thatched roofs pargetting, village signs, you name it. Sadly, she still does not understand real ale. Or brown sauce. In all other ways she is more or less normal Apart from being the only person to say “Holy Cow” outside of a Batman cartoon. Oh, and a ghoulish obsession with skulls on funerary monuments. Where my photography is slapdash, hers is meticulous. And it shows. To the extent that I have now invested in my own tripod with a geared head to capture all those carved angels. I have made it a point of pride to use only my own pictures on this website, but I have seen sense and now readily supplement my own with some of hers if we have visited a place together. So here are a few non-church pictures of Thaxted by what she would call my “Church Buddy”. My sincere thanks to her. The next lunch is on me, Bon! |

|

|

|

Two of Bonnie Herrick’s pictures of Thaxted’s fifteenth century Guildhall, one of the most iconic buildings in the East of England, never mind Essex. You can see the church (literally) towering over the town in the background. Thaxted is a splendid place to visit. |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|||||||||||