|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

outfall into The Wash. In those days Wisbech, just five miles away, was a coastal port. In days when overland transport was slow, hazardous and cripplingly expensive the Nene was an important commercial artery, taking produce and even limestone, from the Midlands to the sea and thence to London. Today, when Peterborough and London are are a hundred miles and just two hours apart by car this seems almost inconceivable but such were the economics of mediaeval transport. In the eighteenth century the course of the river was rerouted between Peterborough and the sea, thus leaving Upwell - literally - on a backwater. This change in commercial fortunes, of course, explains why this small settlement boasts such an imposing church. And talking of limestone, this church is made from Barnack stone, one of the most famous of all English quarry stones and used in the construction of four cathedrals. Barnack (which also has a famous church) is a couple of miles outside Stamford in Lincolnshire - and you can still walk your dog over the site of the quarry!. At a distance of only ten to twelve miles the cost of road transport exceeded the cost of the stone itself. We can be pretty sure then that the stone got to Upwell by being taken by boat along the River Welland to where it meets the sea at the western end of the Wash; thence by sea to Kings Lynn at the eastern end of The Wash for the short river journey to Upwell on the Nene. Architecturally, the church looks much of a Perpendicular style muchness with the exception of the tower. Most of the tower - awkwardly placed at the north west of the church - is in the Early English style of the early thirteenth century. The top section of the tower is in the Decorated style, probably late fourteenth century. Then things get less assured. Pevsner noted that there is a tower arch within the church, these days leading to the fifteenth century north aisle. From that he deduced that the nave of the thirteenth century church originally occupied that space. Thus, so his reasoning goes, the tower then occupied a perfectly conventional position at the west of the nave and but was then marooned where it is in this odd position by the building of a later nave and an aisle to its south. He says that nave was started in around 1300, citing the tracery of the west window and the style of the west door. Unfortunately, my understanding is that the west window is in fact modern and, as I will show below, that doorway is of around 1400 and definitely not of 1300. An alternative narrative is that the nave was always where it is now; that is that it was contemporary with the tower. Then, so this version goes, the nave was rebuilt in the Perpendicular style in the second half of the fifteenth century and that its west wall masonry (although not its window and doorway) are thirteenth century. My own belief is that Pevsner was right: that today’s nave was a new build and not a rebuilding. The glory of the church,, however, is its angel roof which is fit to be mentioned alongside the many excellent ones in adjoining Suffolk and the finest of them all, the famous St Wendreda’s in March, Cambridgeshire. March itself is only eleven miles away by road and is the only substantial town on the Middle Level Navigations. As we shall see, however, “angel roof” does not do justice to Upwell’s. The whole roof is a mass of carved figures of every sort and although March’s magnificent squadrons of angels are indeed the nonpareil, Upwell’s is rather more interesting. And not only is it more interesting but is also highly visible and the reason for that is that the church has a surviving west gallery - unusual but not a rarity - and also a north gallery running the length of the nave which is very rare indeed in a church of mediaeval origins. Quite why the brutal Victorian architectural gauleiters who hated such things allowed it to survive is anybody’s guess. But survive it did and from both galleries you have the perfect vantage point to get up close and personal with those angels! Less remarked upon in other church gazetteers are three quite lovely mediaeval doors to north, south and west of the church. The one inside the north porch is easy to overlook as the porch itself is behind a locked iron gate; but you can clearly see the door with a repeating pattern of birds - possibly swans. Finally, Upwell forms almost a continuous four mile linear village with its neighbour Outwell. Outwell’s church is the poor relation in most eyes and is largely ignored. But it too has a few surprises and is well worth a visit for its mediaeval glass. Click here to see it. |

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: The very untidy-looking west end, badly marred by the rendering at ground level. It is, however, an invaluable guide to how this church developed. The two lowest stages of the tower are Early English, the lantern-like octagonal upper stage being of the fourteenth century. Note the window of the second stage with “plate tracery” - that is, the stone at the head of the two lights has had a quatrefoil hole punched through it - the very earliest form of gothic tracery. As previously discussed, one version of subsequent events says that the west wall of the nave is also EE but only as far as the string course two thirds of the way up. Pevsner’s is that this wall is part of a new nave replacing one now occupied by the north aisle. To the left is the west side of the north porch - a large one and also plonked right at the west end of the church so that you are seeing here four different “cells” of the church more or less flush with each other at the west end. It looks awkward and inelegant. The Perpendicular style of the windows of all of these cells tell you that there was indeed a major rebuilding exercise here in the fifteenth century. The west window of the nave, however, is a modern insertion. That fifteenth century program saw a rebuilding of the north aisle, either the rebuilding or the construction of the nave and (again) the a rebuilding or construction of a new enlarged chancel and the addition of the south aisle. It was, to all intents and purposes an almost complete rebuild. Over what period of time, however, is unknowable. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: Looking to the east. It is a view uninterrupted by any any rood screen and the chancel arch stretches across the entire width of the chancel. The identical arcades to north and south and the similarity of the mouldings to those on the chancel arch demonstrate the extent of the fifteenth century rebuilding program. Right: The late Georgian south gallery is a very rare and striking survival. This is hardly a small church so it speaks volumes for the size of congregation that this church was handling at that time. Looking at the somewhat sleepy little settlement that Upwell is today it is almost hard to credit. The arcades are striking in the complexity of their moulding but the upward sweep of the columns interrupted only by the most token of capitals gives the whole church a feeling of elegance. |

|

|

|

|

Left: Upwell has three very fine mediaeval doors. Left: The west door which is the entry to the church today. Centre: the south priest’s door. Note the keys of St Peter to whom the church is dedicated. Right: The north door within the porch which, surprisingly, is kept locked behind an iron gate. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Detail at the top of the west door. Look at how the carpenter has undercut the wood. Right: Detail of the north door with its Perpendicular archway designs and a border of carved swans. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Label Stops. Left and Second Left are at the entrance to the north porch. The tongue poker is a favourite label stop theme. Second Right and Far Right: These two are on the west doorway and they are rather interesting. The jovial-looking man might at first sight look like he has a king’s crown but it clearly is not. I have a theory that masons often recorded themselves or their colleagues on label stops and I suspect this is one such. I find it rather odd that nobody (as far as I know) has suggested this before me. People talk airily of “patrons” and “local worthies” and I am sure that is sometimes true. But head gear like this appears a lot on label stops in the east of the country and I can’t for the life of me think why stonemasons - who famously carved more or less what ever they liked on the outsides of churches - would be the only artists in western history who chose never to leave their own signatures. The man on the left could also be a mason, of course. The (rather pretty) lady on the right intrigues because the square shaped headdress she is wearing dates from a very short period across the later fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries - say 1390-1410. This doorway , then is not part of a thirteenth century nave nor part of the suggested late fifteenth century rebuilding but somewhere in between. This suggests that Pevsner may have been right that the present north aisle is on the site of the original nave and that none of this west wall in thirteenth century.. But he was wrong to suggest that the doorway (and the probably modern window above it) is evidence that the later nave was begun by 1300. This carving demands that we believe it to have been started around 1400, not 1300. Moreover, the door itself (see above) has cusped Perpendicular style ornamentation that fits 1400 but certainly not 1300. I actually think this was slip of Pevsner’s pen! I am inclined to believe that there were a number of fifteenth century building phases here or else a very protracted an possibly interrupted program. The roof, however, is very much of a piece and must have followed the final phase of building. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The imposing chancel with its rather unusual east window which is, unsurprisingly, nineteenth century, not mediaeval. Centre: Looking towards the west with its wooden gallery. You can just make out in some of these pictures the angel roof above but it is impossible to make them properly visible without washing out the rest of the pictures! Right: The Perpendicular style south aisle as seen from the west gallery. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two Pictures Above. Two of the angels seen uniquely up close and personal at the west end of the nave from the west gallery. Note the disembodied wings on the wall plate behind the main figure in the lower picture. It looks like their bodies have been removed. A case not so much “angels without wings” but of “wings without angels....”. In the upper picture you get some idea that this is no ordinary angel roof. There are angels on the wall plates and on the cross beams and a course of carved fleurons besides. And we will see that this is not the half of it! Wouldn’t you like to have a really long handled feather duster to use up there?! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The face of an angel. At this sort of close-up distance you can almost see the chisel strokes. Right: Yet another angel, this time on a cross beam. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

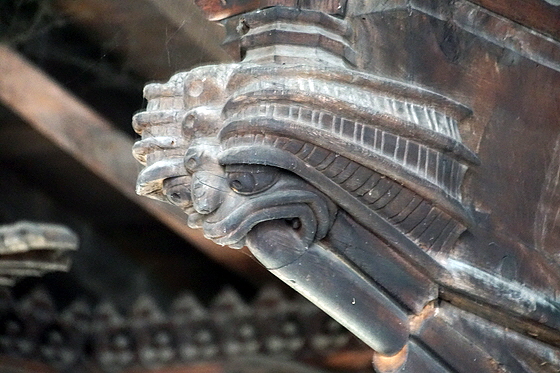

This picture tries to do justice to the array of carving here that would not be out of place in Suffolk, the doyen of counties where timber roofs are concerned. In the foreground a man is grabbing the heads of two women who don’t look much like angels to me! There are similar carvings on all of these hammer beams. An angel sits on the cross beam. Others are visible on the wall plates. At the end of the beam a grotesque eats his own perch. Just visible on the right you can see that the uprights are carved too. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

As you can see, all mediaeval life and fantasy is on the roof and these carvings are much more interesting than the angels - impressive as they are - that everybody bangs on about. There is a recurring theme of people and creatures being eaten by other creatures (my favourite is the fishy dragon second down on the right) but there are unicorns, eagles and rams here too. A feast. If you haven’t got a long lens on your camera then take binoculars. As you can see, the carvings are on both the east and west sides. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A long-tongue monster at the end of a roof support. Centre: At the other end a tongue poker sits happily next to an angel. A study in the ambiguity of the mediaeval artistic world. Right: The octagonal Perpendicular style font with a plethora of blank shields. We might well wonder why there are so many of these on church fonts. But the answer is that they were probably painted with heraldry at the time. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another monster anxious to eat his own support system! Right: It is worth reiterating that one of the things that makes Upwell’s timber roof carvings so impressive is that they span the whole church including the aisles and not just the nave as is more usual. Here we see angels adorning the north aisle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Royal arms used to be mandatory in the post-Reformation period to show the supremacy of monarch over church. They would be a fruitful subject of study by someone out there. I don’t think there is even a Shire Book on the subject, which is the measure of obscurity in a country of infinite eccentric hobbies and pastimes! Upwell Church upstages everybody by having two and both are carved than being in the usual form of being painted on boards. Left: Mounted on the north gallery is this particularly impressive piece. The unicorn is particularly splendid with a somewhat sardonic smile on his face. “And you thought we were mythical, huh?”. Right: This specimen is mounted at the west of the church. The insignia and motto of the Order of the Garter is at its centre. Both lion and unicorn are lean and mean compared with their tubbier counterparts on the north gallery! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This brass mounted on the north side has lost its inscription but is believed to commemorate William Mowbray, the rector in 1428. Centre: The organ. Right: The pulpit. |

|

|

|

|

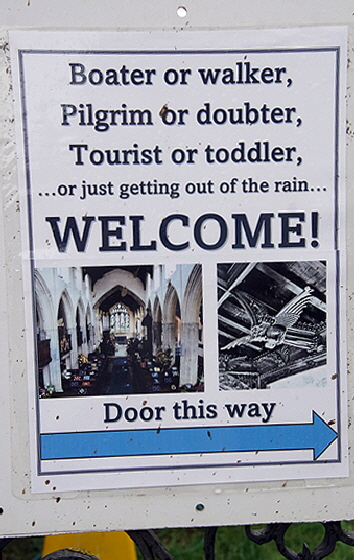

Left: The splendid swan carvings that surround the whole of the north door. Centre: The west window of the uppermost stage of the tower. It is a very interesting composition. Norman and Transitional had now given way to Early English. The pointed lancet window was the most iconic feature of this style and here we have a pair carved with a precision that would have been impossible for all but the most skilled of masons fifty years previously. Then the masons enclosed it with another arch and a hood mould. Tracery was not yet “invented” but we see a trefoil cut right the masonry - what we now call “plate tracery” - which was a forerunner of the real thing. Right: A sight to delight any church crawler. Bravo, Upwell! What a contrast to the many “It’s ours, nor yours, we keep it locked, sod off” attitudes of too many churches. Norfolk, however, is amongst the righteous counties! |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

Left Upper: The church from the south east. What a very forthright and commanding building it is! Left Lower: Looking from the church along the “High Street”. Well Creek goes under a bridge behind the car right of picture and emerges on the other side of the road where it is flanked by buildings on either side, more or less until it reaches Outwell four miles distant. It is an isolated and atmospheric spot, in common with most fenland towns. Right: The imposing view of the north porch with the tower behind it. There is a parvise room above the porch with a rectangular Perpendicular style window. It is flanked by two empty niches. Beyond the iron gates the porch is vaulted. |

|

Footnote - The Wisbech & Upwell Railway |

|||

|

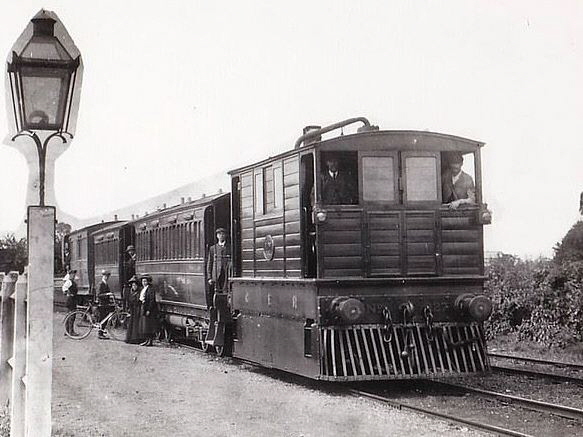

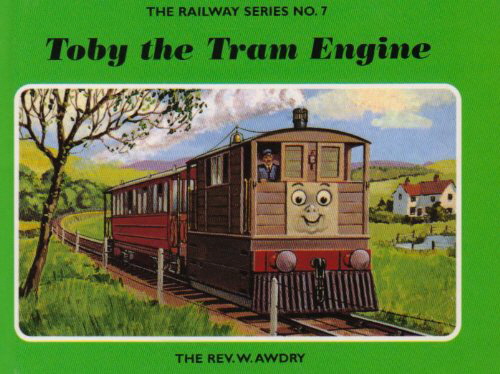

All of my four children will remember the “Thomas the Tank Engine” stories by the Rev W, Awdry with great affection. They had all of the books, cassette tapes of the stories (yes, I’m afraid it was that far back) narrated by Johnny Morris and watched the TV series narrated by no less than Ringo Starr! One of their favourite locomotives was Toby the Tram Engine, a tiny and unorthodox little locomotive with its wheels covered by sideplates and a device called a “cow catcher” which was there to clear the tracks of any obstructions including, one presumes - and hopefully gently - cows. To this day, the family Wall might stumble on something lost or unexpected and say “Aha. Aha-a-ah. Where’s your cowcatcher then!” To which the required answer is (in a very reedy voice) “Please sir, I don’t catch cows”. Toby was based upon a real locomotive on a real railway and that railway was the Wisbech & Upwell Railway. Remarkably, it was a largely passenger railway originally but freight traffic was its bread and butter. Farm produce from the Upwell and Outwell area was transported to Wisbech and coal (am I still allowed to use that word?) went in the other direction. Opened in 1883, it survived remarkably until 1966. Because the railway mainly operated alongside roads the locos were required to have their wheels covered as well as other unorthodox “safety” measures. Outwell had two stations: Outwell Village and Outwell Basin. Upwell had just the one. The unorthodox design of the locomotive built for this line (and upon which Awdry based Toby the Tram Engine) is shown in the photograph below. They were built in 1883 at Stratford Works and, remarkably, were not scrapped until 1952 when they were replaced by more powerful and more conventional locos. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

|

|

|

|