|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

scepticism. Pevsner made the same claim for the chancel arch which is stranger still. The church must be valued for its antiquity and its architecture rather than for any dazzling treasures so let’s just look at the pictures. |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel arch is big and uncompromising. Don’t look for subtleties here: its only decoration is two courses of zig zag moulding. Note that the profile is very far from being a perfect semi-circle. The windows visible to left and right are restored early thirteenth century lancet windows. Just visible to the right is the blocked triangular-headed doorway. Right: The chancel. The east window is of the fourteenth century in the Decorated style and with reticulated tracery. There are two pairs of Early English lancet windows to north and south. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: Above the putative filled-in chapel doorway is an original Norman window. Looking at the geometry here it is hard to imagine that there was a chape: there is simply no room. To the left of the doorway is the small EE lancet. Centre: The mysterious triangular-headed doorway. You might be tempted to speculate that it was the original south doorway to the church, and it this church is from AD1100 a doorway of this profile would not be so very surprising., although its position is a little odd. This idea is supported by the later date of the current south doorway. Right: The south doorway. That it is late Norman is obvious not only from the subject matter of the tympanum but also from the rhomboidal course of decoration and the uninterrupted flow of the door jambs. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The tympanum is badly weathered and you will have to take my word for it that is depicts the !Coronation of the Virgin”. The rhomboidal decoration is very poorly executed, Perhaps this is what prompted Pevsner to think it came from elsewhere. Personally, I think it was just a bodged job by a mason out of his depth. Right: The lens makes the nave look longer than it really is as you can tell from the much-enlarged Norman windows to left and right!. Nevertheless, it is of surprising proportions for its time. The west end is distinctly messy with its organ and a surviving west gallery. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south east, showing the Early English chancel windows and priest’s door. Note the corbel table. This is a conspicuously large church for the early Norman era village church. See my footnote below. Right: The north side seen from the west. We can see a Norman window and a filled-in Norman north doorway. Again, note the corbel table. |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

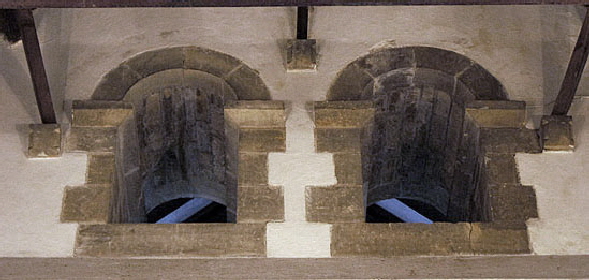

Left: The west tower. The rectangular windows are later replacements. Centre: The plain chancel arch columns. Right: The inside of the south door. Like the outer doorway it is very simple. In fact, it is rather odd in that it is more rectangular than arched. It all adds to me belief that this doorway simply wasn’t very well executed. And that would be the case whether or not you bought Pevsner’s notion that it had been moved here from elsewhere, |

|

|

Corbel tables are one of the delights of intact Norman churches. Some have imagery that delight and fascinate in equal measure: see, for example, Kilpeck (perhaps the most famous of them all) and Elkstone. Worth’s is crude and uninteresting by comparison, but this is an early Norman church and, as we have seen elsewhere in the church, the masons do not seem to have been the best that money could buy! This is one of the section of the corbel table here at Worth and is typical of the rest. |

|

Footnote - Why is the Church so Big? |

|

“Big?”, I hear you saying. “It’s half the size of my local church”. Right. But this is an unextended early Norman church and it is surprisingly hefty. You might feel that this is reinforced by the fact that the parish has never felt the need to extend it. When I talk to people about the history of the English parish church one of the first things I say to them is that they must not run away with the idea that churches were built by the Church. Justin Welby and his predecessors, it is true, treats them as his to tax and dispose of as he sees fit. Most churches, however were built by lay patrons and parishioners in differing measure and, it is easy to forget, usually centuries before the Church of England was even established. Monasteries sometime built churches outside their monastic precincts, but mostly they preferred to be gifted churches so that they could plunder their tithes! Worth Matravers Church will certainly have been built by the local bigwig and here the Domesday Book becomes useful because this church was built less than twenty years after it was compiled. At the time of the survey (1086) the land was held by one Roger Arundel. The book lists several holdings. Some were held by him “of the King”. Others - including Worth - were held “himself” and others were held “of him”. Thirteen are listed in all. Worth was the largest of these. There was land for “twelve ploughs”. In demesne (that is, farmed by Roger himself) four ploughs. He had eight slaves, which is sobering. Serfdom is something most people hear about at school, but less so about outright mediaeval slavery. There were eight villeins (serfs) and nine “bordars” which were much the same thing. There was a mill “rendering 7s 6d”, fifteen furlongs (nearly two miles) of meadow and the same of pasture, as well as woodland. The whole was worth, Domesday reckoned, £16 7s 6d. In Saxon times it had been held by one Aethelfrith and interestingly he paid geld - tax - for sixteen and a half hides. A hide was sufficient land to support a tenant farmer and was about one hundred and twenty acres in Norman times, although probably somewhat less in the pre-Conquest period. The sixteen ploughs, however, tallies very neatly with the sixteen and and a half hides and certainly amounted to the same thing. So Roger was a wealthy man, and his biggest holding seems to have been Worth Matravers. The church would have been built solely by him and - again. something hard for people to understand today - would have been owned by him. Churches then were private property. That was probably why they were sometimes listed in Domesday Book. Roger was probably making a statement here by building a church that on the face of it was over-large for its community. Incidentally, you can see on this website the church of Melbury Bubb, also held by Roger Arundel at that time, and which has a very important tenth century Anglo-Scandinavian font. |

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

|

|