|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

cloistered themselves within a closed community as we now think of monasticism. They would - as the name implies - ministered to the religious needs of the surrounding communities, most of which, perhaps, would have had no ecclesiastical buildings or priests of their own. It is quite likely that as a minster church it was one of the rare ones built in stone. But of it there is no trace. The earliest parts of today’s church are the lower sections of the tower and the transepts which date from about AD1210, just as Norman architecture was giving way to the new-fangled Gothic with its pointed arches. It is a cruciform church.. This “Transitional” look is evident in the bell openings which are a mix of styles but decidedly no longer simply Norman in character. Tall pointed lancet windows in parts of the transepts are pure “Early English” Gothic. The aisles followed about a century later under the auspices of John de Straforde, later to become Archbishop of Canterbury. As was often the case, especially in the fifteenth century and especially in the mercantile towns, these aisles seemed to have been predominantly to provide space for extra altars. De Stratforde wanted a chantry for the donors in the south side and the town’s religious guilds had three altars in the north. Doubtless, these guilds also made large contributions to the costs. The church really assumed its present “look”, however between 1480-1520 under Deans Thomas Balsall and Ralph Collingwood. The chancel was completely replaced. The west end of the nave remodelled and the north porch -still the main entrance - added. The clerestory was also added. So impressive is it that one could claim it to be the most striking feature of this church externally, apart from the tower. It is tall and almost entirely composed of glass. It is, in fact, a typical product of the wealth of England’s wool-producing areas and you will see similar in Gloucestershire and Suffolk, among other counties. This was, of course, the Perpendicular style that took root after the Great Plague of 1348. The Reformation was as severe on collegiate churches with their cadres of priests saying masses for the great and the good as they were on the monasteries. Stratford lost all of its chantries and guild altars and just became the parish church. It could consider itself fortunate: many a former collegiate or monastic church saw large parts of their structures completely demolished, So what would you come here for? Well primarily, of course, for the Shakespeare graves inside the chancel. Those paying to enter the chancel make a bee-line for them, i-phones ready to capture it all for family back in Beijing, Bangkok or wherever, As an Englishman - and more to the point, a man of Warwickshire - this makes me very proud. The great shame is that the very fine set of twenty-four misericords does not attract the attention it deserves. These give an insight into English mediaeval mindsets but few give them more than a cursory glance, distracted as they are by Will and his missus. Shame. But a deserved call out for the churchwardens here who leave the misericords in the “up” position so that the designs can be seen and photographed. Many cathedrals don’t and I am going to have a little rant about that later. There also fine monuments in this church, doubtless informing Jenkins’s otherwise rather generous four stars. In truth, however, 99.99% of visitors will be here for Will. I only hope that this page will inspire you to look beyond all that and make your visit more fulfilling. |

|

||||||||||

|

The chancel Shakespeare’s effigy in to the right of the doorway on the left. The family tombs are just beyond the brass rail in teh foreground. .Note the superb triple sedilia on the right. |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Left: looking along the chancel with the misericord ranges to left and right. Right: On the north wall of the chancel are William Shakespeare’s memorial tablet on the left. Right: The memorial to Richard and Judith Combe. Judith was Richard’s cousin whom he intended to marry but she died in his arms in 1649 before they could be wed. |

||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

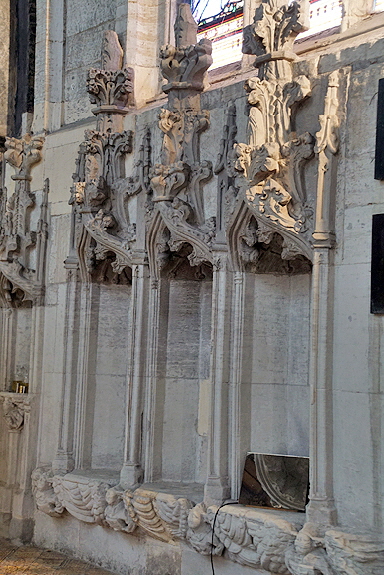

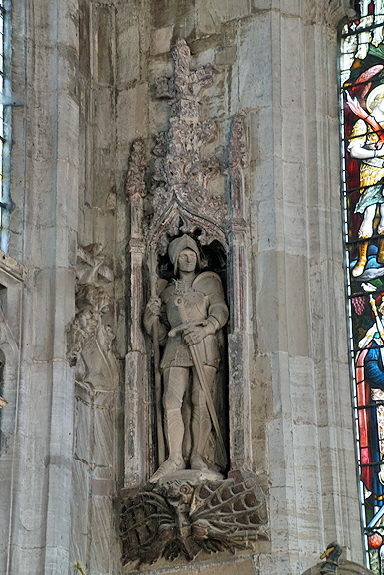

Left: The triple sedilia is as gorgeous as you will see anywhere. Look at the complexity of the hood carvings. Then at the very rare carvings of angels at the edges of the seats. Not visible in this picture are Tudor roses carved on the undersides of two of the canopies. Another has Christ. We can only surmise that the iconoclasts missed it. Centre: The stytius niches either side of the east window are equally superb. The statues, of course, are modern replacements for those destroyed at the Reformation. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Shakespeare’s grave. The rather peculiar curse on “he that moves my bones” is taken by some to reference the mediaval practice of removing bones from the churchyard and piling them into an ossuary such as still can be seen at the only two surviving sites at Rothwell in Northamptonshire and Lydd in Kent. Centre: Between the north aisle and the north transept is a space now called “The Clopton Chapel”, its original use as a Marian chapel having been outlawed at the Reformation. The Cloptons were a wealthy and powerful local family: The town’s main bridge over the River Avon is called Clopton Bridge to this day. This monument to George Carew (d,1629) - later Baron Clopton - is described without exaggeration in the Church Guide as being regarded as one of the finest renaissance monuments in Europe. Carew served three monarchs and was James I’s Master of the Ordnance, His position is thrillingly displayed at the base of the monument where you can see powder kegs, cannon barrels , cannon balls and a musket. Right: The south transept. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This doorway to the north west of the chancel led to what the Church Guide describes as being the charnel house (more usually described as as an ossuary in this context) where Shakespeare allegedly feared his bones would end up. The extraordinary thing about this doorwat is the unprecedented level of decoration and the sheer size of those capitals. There is nothing incidental about them. Right: In the Clopton Chapel is this monument to Wlliam Clopton (d.1592) and his wife. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view of William Clopton’s memorial. Right: Just as interesting as William Clopton’s tomb chest, if not more interesting, is this wall monument placed above it where Clopton’s weeping children are displayed. There may be other examples of this sort of separation but I can’t think of one off hand. Indeed, the norm would have been to place the weepers around the base of the tomb chest. Note amongst the children three swaddled “chrysoms”: children that died within a month of baptism. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The carving on the end of the hood mould of the door to the charnel house. It is damaged but this represents St Christoper - his feet shown clearly as being in the water. Christ on his shoulder has been defaced. This is a remarkably ambitious - and large - carving for a hood mould! Centre: The sanctuary knocker on the north door. Right: The north door itself. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end. Right: It was a horribly difficult day for photography with all sorts of paraphernalia getting in the way - TV screens, Christmas trees to name but two in this most tourist-orientated church. Hence this rather odd photograph where I have tried to capture the lavishness of the clerestory - a wall of glass above the north arcade. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west front with its remarkable combination of elaborate Perpendicular style window and (empty) triple niches. Centre: Mediaeval doors are frequently overlooked by the casual visitor. Especially in the Perpendicular “period” - say 1350 to 1550 - it was common practice for all manner of furnishings - doors, pulpits, screens, stained glass images, fonts - to reflect the prevailing architectural style. Shoiuld you wish to bamboozle your awestruck friends - this phenomenon is known as “skeumorphic”. Right: The very unusual tower. Its base is Transitional or early Early English (take your pick!) but the rose windows at each cardinal point - surely unique in a parish church? - are early fourteenth century. The battlements and spire were later additions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Misericords |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For my part, nothing attracts me to a church or a cathedral quite as much as a misericord range. I am not going to explain yet again what they were for - you can find that out on several other pages of this site. What delights about misericords is that here more than anywhere else in a church images of everyday mediaeval life, satire and humour come up hard against the piety of the mediaeval church .For these misericords were placed, by definition, in that most sacred of church spaces - the chancel. We modern people can tie ourselves in knots trying to make sense of this contradiction within the context of our own twenty first century sensitivities but this is another area where you are just wasting your time! You must live with the fact that mediaeval people, including the clergy, had a much more robust attitude to the juxtaposition of sacred and profane. They knew what mattered and what did not and you would have to say, I think, that their attitudes were much more grounded and practical than our own. A few years ago some parishioners in Yorkshire - non church-goers, of course, - went beserk because the vicar allowed a beer festival in his churchyard. It would be futile to point out to these Social Media warriors that it was in far more religious centuries commonplace for beer to be served inside the church, never mind in the churchyard! But it is sensible to ask why the misericords are here in Stratford. Generally, there are four reasons for a parish church to have misericords. The first is that was a monastic church where the completion of eight offices per day demanded some relief for the poor arthritic monks who could not stand for so long. The second is that it was a collegiate church: a church where there were several priests, some of whom were there to say masses for the immortal souls of the church’s benefactors. They too performed the eight offices per day. The third reason - particularly latterly - was that some well-endowed town churches wanted large choirs; and misericords were one way to provide seating. It is also likely at this time that the grandees of the parish were demanding in return for their generosity privileged access to the chancel, a notion once unthinkable. The fourth reason is prosaic; that at the dissolution of the monasteries and colleges the misericords became redundant and turned up in smaller churches. Old Malton in Yorkshire is an example of a monastic church that survived to become a parish church (although much diminished) and retained its misericords. Another is Christchurch. Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire is perhaps the most celebrated of dissolved collegiate churches and besides two misericords on display in the church, the rest were dispersed over the centuries to Tansor, Benefield and Hemington. Boston and Nantwich are two excellent examples of rich town churches for which the misericords performed a choral and/or lay function. Stratford- upon- Avon was a collegiate church. The trigger as the founding of the chantry chapel of St Thomas a Becket in 1331. Other chantries (by definition, a chapel where masses were chanted) followed, some probably to serve religious gilds as well as the local aristocracy. They followed the Rule of St Augustine and did not live in a closed community in the way monks did. The Collegiate Churches fell when the Monastic houses fell. Stratford segued seamlessly into a normal parish church and retained its misericords. Others such as Fotheringhay lost its chancel and with it the misericords. There are twenty six misericords at Stratford. They were installed by Dean Thomas Balsall who caused the chancel to be rebuilt between 1466-91. They are seat for seat, by any standards, one of the more entertaining groups in England. There is a smattering of foliate designs but hardly anything with any overt religious connotation. Like all of the best misericord ranges, the supporters - the images either side of the main ones, are as, if not more entertaining. It is worth reiterating that supporters are unique to England and that perhaps 95%+ of English misericords have them. The church produces a splendid book of the misericords and describes them all and attempts to “interpret” them. within a Christian context. Whether these interpretations are accurate or wishful thinking well - only God knows and he’s not sayin’. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

As a Warwickshire man born and bred, this is one of my favourites. Two chained and muzzled bears at a ragged staff. To this day a single bear at a ragged staff is the county emblem of Warwickshire. They are the emblem of the Earls of Warwick who were, to say the least, pretty important at that time. Richard Neville - the “Kingmaker” - died in 1471. The supporters both have that staple of mediaeval satire, the monkey. One is examining a bottle of urine and the other is - er - filling one, This was quite a common mediaeval satire: that the medical profession felt that every ailment could be diagnosed via a urine sample. I believe it also refers to the idea that apothecaries were prepared to sell their own urine to the gullible. Right: A camel supported by two wyverns (two-legged dragons). In mediaeval Bestiaries the camel was described as living to 100 years old and preferring to drink dirty water, trampling in clean water to make it more palatable! They also “hate all horses”. The Church Guide says that the Camel, because of not needing to drink for long periods represents the virtue of temperance. My Bestiary refers rather to the saying of Christ that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God and that the camel, therefore, represents the humility of Christ. Take your pick. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A naked woman riding on a stag. The Church Guide points out that her hair is loose, denoting a “loose woman”. It suggests she is surrounded by the beauty of the world (roses, ears of corn etc) and rejecting the Virgin Mary, A warning to men (of course) to reject Satan as embodied lustful women. Sigh. Right: A sphinx with a defaced rider. More interesting are the supporters. On the left a man and a woman are fighting. The man has seized the woman’s long hair (another harlot then!) and is getting a boot in his groin for his pains. Makes my eyes water just looking at it. On the right a man seems to be birching a woman on her bare botttom. To compoind her woes, thea dog has her by the leg. The Church Guide suggests that this was seen as the best course of action - beating the cow into submission whereas the other scene showed what happens when you let a woman have too much latitude. Charming! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: I agree with the Church Guide on this one. We are used to thinking of the Owl as a symbol of wisdom. To Christians it was the symbol of someone who lived away from the light of Christianity. Sadly, the main focus of this ire was often the Jews. Right: A defaced St George skewers the Dragon. The Virgin kneels in prayer. The supporters show “men” with beastly hindquarters combing their respectively their hair and their beard. beard. Vanity, All is Vanity! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An eagle sits below a coronet held by two hawks. The eagle is Christ. Grotesques support. Right: Great interpretation by the Church Guide here. Christ is depicted as a unicorn. (a representation mentioned in the Bestiary). On the unicorn’s right a hunter driving a sword into him, representing the men who carried out the crucifixion, The maiden is Mary. The three crosses on the shield represent the Trinity. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Few large misericord ranges would be complete without a a scene of husband and wife fighting. As usual, the woman wields a ladle and has the man by his beard. She clearly has the upper hand. The Church Guide sees this as another warning against a man failing to control his missus. Myself, I see it more as a piece of fun. The “world turned upside down” was a popular mediaeval theme that often included animals playing instruments, for example. The supporters are the “IHS” pf the Greek for Jesus Christ. It seems an odd choice of supporter in this context. Right: An human face in oriental headgear - a heathen. The duck on the left, the Church Guide tells us, is symbol of honesty, fidelity and simplicity. none of which is mentioned in the Bestiary but I am sure there were other sources. The bird on the right is alleged to be an ostrich (who knew?) with a horseshoe in its beak to ward off Satan! it is curious to see a modern superstition in currency six hundred years ago. Wikipaedia offers this insight: “The superstition acquired a further Christian twist due to a legend surrounding the tenth-century St Dunstan, who worked as a blacksmith before becoming Archbishop of Canterbury. The legend recounts that, one day, the Devil walked into Dunstan's shop and asked him to shoe his horse. Dunstan pretended not to recognize him, and agreed to the request; but rather than nailing the shoe to the horse's hoof, he nailed it to the Devil's own foot, causing him great pain. Dunstan eventually agreed to remove the shoe, but only after extracting a promise that the Devil would never enter a household with a horseshoe nailed to the door.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A mermaid is sitting on the right, combing her hair, her other hand clutching what would have been her obligatory mirror. But what’s this on the left? A merMAN, forsooth! he holds a stone in his hand. The Church Guide opines that he has succumbed to the slatternly siren charms of the fishy lady. Well, maybe. I prefer to think that just possibly women could list after unattainable men as well? Right: Two entwined figures with serpent-like bodies. Another serpent-tailed figure on the left supporter plays a pipe. Another on the right is emerging from a fish - you need to look carefully. The man holds the fish’s tail in one hand, a sword in the other. I would have thought that he was going to kill the fish to avoid being eaten but the CG inventively suggests that the fish here represents Christianity and that he is holding his sword to show allegiance to the faith. Who would have thought it? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: We love misericords as the best repositories of mediaeval weirdness. It’s a packed field. This misericord is, for my money, the very epitome of weird. A (defaced) man and a woman emerging from whelk shells! The woman holds distaffs for winding wool and she also holds a card for carding wool. The man holds a flesh fork. Even the ever-inventive Church Guide is at a loss, I reckon, describing it as just a celebration of mediaeval life. But whelk shells, for heaven’s sake? Right: A lion with two bodies. Two wyverns support him. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The eagle and child. The eagle, the king of birds, rescues mankind in swaddling clothes. The lion on the left is in “coward’s” pose. On the right is a half man, half lion. Right: A wanton woman with naked breasts, clearly lechery. The supporters are harpies (one defaced.). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A satanic face with four horns, The supporters are theatrical masks. Right: Three images of the same woman. The left supporter suggests gossiping or pwrhaps nagging while the supporter on the right shows her with her tongue forced down by a “scold’s bridle”. Can you still buy them? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A mask with a face. The Church Guide sees it as a Green Man. The supporters are faces within four petals or leaves, suggesting a similar theme. Right: A human face with ram’s horns and ears. The left hand supporter is a dolphin, the right a goat |

|

The research quoted here is by Madeleine Hammond, MSc in English Local History. It is a remarkably comprehensive set of interpretations, the like of which I have never seen before. She has been able to put all of these carvings into a Christian context. Some are very obviously true; others are less obvious but I have to admit I was pretty convinced. Doe this mean that all misericord ranges are similarly capable of such interpretation? I honestly don’t know. My view is that mediaeval carpenters and stonemasons were pretty well laws unto themselves when it came to decoration and although some imagery, such as green men and mermaids, were well understood by craftsmen and observers, it is difficult to believe that such intimate knowledge of Christian iconography was possessed by all craftsmen. It is possible that there was, in such a rich collegiate church, some highly educated cleric that was able to guide the carpenter and suggest designs. That would very likely be true in cathedrals and the richest abbeys too. Similar debates surround Romanesque design where a great deal of effort has been expended by modern researchers desperate to “explain” the rich and obscure decorative carving of the time. I am at the sceptical end of that debate, I have to say, and I am so for most mediaeval sculptural carving. Misericords, however, as we have seen, sit within the holiest part of the church - the chancel. Are all or most misericords tractable to such insights as Madeleine Hammond has brought to these are Stratford? Or does wishful thinking - or over-thinking - produce interpretations that would be lost on the thunderstruck craftsmen themselves? In truth, just about every animal and mythological beast seems to have acquired some form of Christian context over the centuries. We know that many are indeed ancient knowledge embodied in such works as the Bestiaries but there are others, perhaps, where modern writers have been eager to invest random decoration with Christian allegory. Anyway, these debates will continue but here at Stratford, I am convinced that all or most of what has been written is not only plausible but likely. Not all the misericords are shown here because some are not very interesting or are badly defaced and, unforgivably, I missed two interesting ones hat were mounted on the walls of the chancel. The misericords here have suffered a level of defacement, as is obvious, but is mild compared with many ranges. Madeleine Hammond poses the plausible theory that the iconoclasts were not understanding the significance of all that they were seeing. Well that, at least, seems certain! |

|

|

|

|

Footnote - A Rant About Misericords |

|

Misericords are amongst the greatest mediaeval treasures of those churches and cathedrals that have the good fortune to still have them. In almost all parish churches and former priories the churches are very aware of their value. They perhaps provide separate leaflets and almost invariably have no problem with visitors looking at them and - in our case - photographing every one! Then there are the cathedrals, And here, I am afraid, we have some cathedrals thats keep their misericord ranges - the best and largest - hidden from the public. They put the seats in the upright position and rope them off from the prying eyes of the great unwashed. If you are VERY lucky you might find a sympathetic verger who will grant you permission to step inside these holy ropes. But often you will meet obduracy. York Minster, lorded over by the No2 Panjandrum in the lofty Anglican Hierarchy, has the gall to charge the public a cool £20 for admission but still puts the misericords out of bounds. My prize goes to the rudest clergyman I have ever met in 15 years of church visiting - at Carlisle Cathedral. This bullying lout in a highly ornate cassock took exception to my ducking under the ropes to pick up a Bible that had fallen off a reading slope , shouted me down when I tried to explain, and accused me of invading “their private space”. Which kind of sums it all up. It’s their’s. B***er off. I do hope the jerk in question gets to read this. Christchurch Abbey have theirs visible so plaudits there. The apologetic verger, however, took exception to our using tripods, without which really good photographs of misericords are difficult. The “Powers That Be” had decreed they were not allowed. Privately he told us that it was thought that only professional photographers use tripods and that they might be taking pictures for commercial gain. The business card for my free website did not exempt us. If you visit Christchurch take your crappiest camera or they might think you are from National Geographic! Who are the people who think up this stuff and haven’t they got bigger problems to solve? At Lincoln it t was earnestly explained to us that we could not enter the choir, let alone view the misericords, because the previous year someone had “torn a page out of a Bible”. Well, yes, I can see that must be a constant threat. As it has been for six hundred years. The choirs of cathedrals are littered with pages torn out by nutters. When we wrote and asked for special permission we were told “it would not be possible”. I am sorry but their posturing convinces nobody. They just don’t want you in there. It must be admitted that misericords are occasionally fragile. In some churches there are one or two that you are entreated not to raise. But this is clearly not the reasoning at cathedrals where if, anything, their misericords are in a better state than in parish churches, We are occasionally proffered a lavish book (at a price) or even a .pdf that shows pictures of all of the misericords. Great. Why go to the National Gallery when you can look at a book? I won’t go on holiday, I will buy a dvd. Why on earth can cathedrals not issue permits for the serious enthusiast? Too many cathedrals are horribly guilty of that old Deadly Sin of Pride. They let the public - whose forefathers funded and built these holy halls - see what they are prepared to let them see. The Cathedrals are “theirs”. In my many travels around the parish churches of England this phenomenon of a remote and proud hierarchy is all too easy to see. Your roof is leaking? Tough. Do some fund raising. We can’t afford anything from our £1bn annual revenues (yes, you read that right. I haven’t invented it.). Send your 80 year old churchwarden on a Safeguarding course (never mind that you have a congregation of 12 with an average age of 75) while we cover up for sexual predators within our ranks. Send us £30,000 parish share from your congregation of 10 (I’m not making that up either) we need a £100m slavery reparation tund (or that) to show everyone how embarrassed we are for our imaginary sins of three hundred years ago. And don’t moan simply because you haven’t had a vicar for two years or are having to share one with five other churches. Just give us our dough. Mentions in Despatches here for the Cathedrals of Ely, Chester and Norwich who, sometimes with a bit of pleading, made reasonable accommodation for us. |