|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is likely that it was funded by an endowment by Lady Aelfigu, the widow of King Edmund I of England (AD920-46) and mother of Kings Edgar I (AD944-75) and Eadred (r.AD955-9). Beneath the apse is a crypt, presumably to house relics. Other known pre-Conquest crypts were at Repton in Derbyshire and at Brixworth in Northamptonshire. Repton’s was the burial site for one of the lines of the Kings of Mercia and is supported by columns. Brixworth’s is no longer accessible but its crypt, like Wing’s, was a shrine for relics. Both were supported by stone pillars. The one at Wing can still be seen through barred gates and the inner sanctum is hexagonal. Around it is an ambulatory through which, presumably, the relic could be viewed. The pre-Conquest origin of the nave is proven by a bifora window of Anglo-Saxon design at the top of its east well, giving out onto the roof of the apse. It is likely that there was an upper room above the lost original chancel and Taylor & Taylor hypothesised that there was indeed an upper floor throughout that original structure. The revelations continue with the existence of blocked doorways at first floor level on both sides of the west wall of the nave. These doorways led to the outside of the church. Their existence is regarded as the best available evidence that many pre-Conquest churches had west galleries. Most Anglo-Saxon west walls have evidence of former doorways, for which a gallery seems the only rational explanation. Pevsner speculated that Wing’s may have been the private gallery of Lady Aelfigu herself. At most churches the hypothesis is that such a gallery was used for the display of relics to the congregation. One must wonder if Aelfigu was really likely to have scaled tall ladders from the outside so I prefer the more prosaic - but unprovable - alternative theory. I should mention at this point that the church would have been a minster church - one form which monks went forth to ad(minister) to the religious needs of the surrounding communities and it would have been the personal property of Aelfigu, her predecessors and successors. It was much later that such churches were subsumed by the emergent parish system. The chancel arch is enormous and like the aisle arches it is simply cut through the wall with no decoration or adornment. Compare it with the monumental chancel arch at Wittering in Cambridgeshire. Such is the significance of the church as a nationally important pre-Conquest survivor that its post-Conquest features seem too insignificant to seem worthy of mention. Simon Jenkins, in awarding the church four stars, mentions the three Dormer family monuments and perhaps this is one of the few English parish churches in which they are doomed to be the sideshow rather than the main event. They are very fine. Pevsner said of the 1552 monument to Sir Robert Dormer that it is the finest of its date in England and “of unparalleled purity of its renaissance elements”. The dark and brooding rood screen looks somehow incongruous here but in the spandrels of its bottom panels are carved birds and faces, a device ubiquitous in Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk but less common in this part of the world. This is a connoisseur’s church, to be sure; one which stands with the likes of Brixworth, Great Paxton, Deerhurst (Gloucestershire), Escomb (Co.Durham) and Bradford-on-Avon (Wiltshire) amongst others as more or less intact - if somewhat altered and diluted - survivors of the “Anglo-Saxon” period. Try to see them all! |

|

|

|

|

Left and Centre: The extraordinary polygonal apse. Two courses of stripwork decoration are visible: blank arches and - near the roof - v shaped courses. Within the latter you can see filled-in original Anglo-Saxon windows. Vertical pilaster strips run from ground to roof. The gothic windows are unfortunate but also, of course, absolutely necessary. One can only imagine how dark the apse would have been originally. At the base you can see arches through to the crypt, the one one in the foreground furnished with a (modern!) stairway down to crypt level and a locked iron gate. Right: I have used Photoshop to “raise” the light in what is still a somewhat dingy church. The chancel arch is original Anglo-Saxon and is simply cut through the nave wall. Note the pair of bifora at the top of the wall, definitive proof if any were needed that this was the original height of the church. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The bifora windows have arches formed from Roman terracotta tiles. Right: The north aisle. The arches are cut straight through the nave walls. On both arcades the easternmost arch has been modified, presumably to accommodate the rood screen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking into the chancel through the rood screen. It is a tall but shallow structure.. The Dormer family monuments to left and right somewhat over-fill it and my use of Photoshop somewhat exaggerates the amount of light. Imagine this apse, though, with tiny unglazed Anglo-Saxon windows, often covered by screens of horn or oil soaked cloth to keep out the weather. Right: Looking from the south east aisle across to its northern counterpart. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The screen spandrel carvings are nicely done but the theme is very much of long-billed birds which may be pelicans. There are a few monsters and heads to break the monotony. however. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

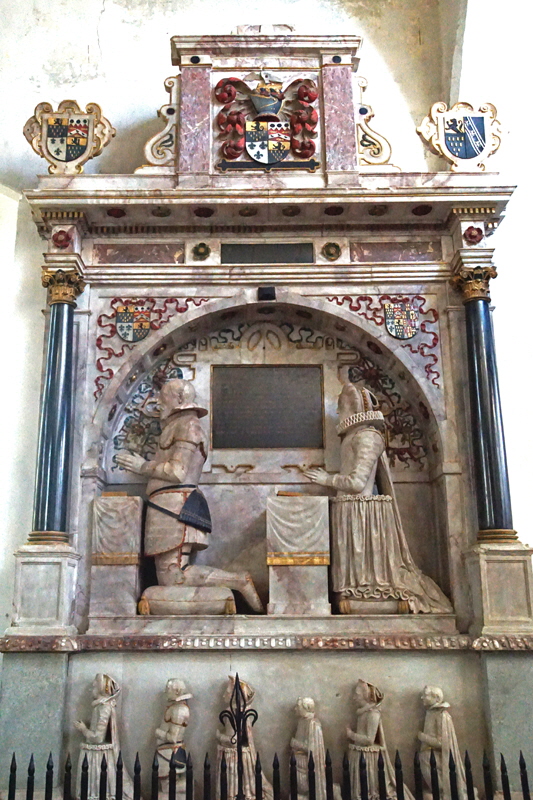

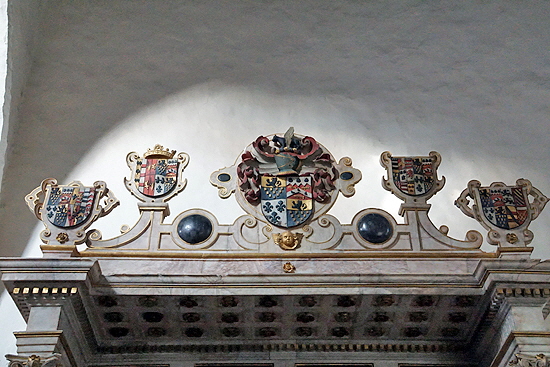

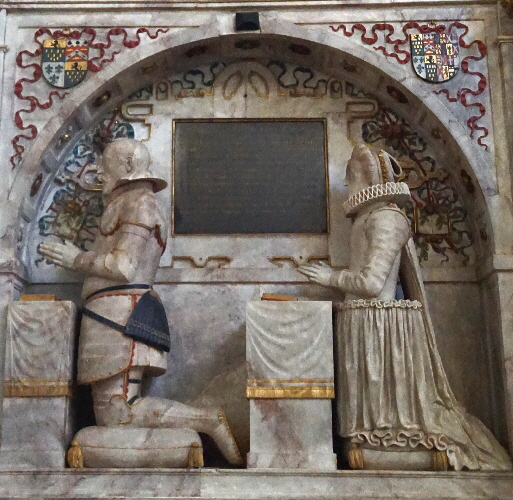

The two chancel monuments. Left: On the north side Sir William Dormer (d,1575) and his second wife who had the monument built in 1590. Sir William was favoured by Queen Mary I but his Roman Catholic sympathies were not in tune with Elizabeth I. Dorothy married into the Catesby family upon William’s death. I have not been able to find her connection, if any, with Robert Catesby who was the ringleader of the Gunpowder Plot, but the Dormer association with Roman Catholic recusancy seems to have been continued under this marriage. Right: On the south side The first Lord (Robert) Dormer (d.1617) and wife and a very fine course of weepers at the base. Like his father, Sir William, he was a minor member of the establishment - Sheriff of Bedfordshire, an MP, a JP - but very rich. He too was a Roman Catholic recusant but it seems he was able to avoid serious trouble via a mixture of discretion and friends in high places. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Top Left: Dorothy Dormer who married Lord Pelham after the death of Sir William. Top Right: Sir William Dormer. Centre Left: Armorial adornments on the Sir William Dormer monument. Above: A particularly fine and undamaged set of “weepers” on the chest of the Lord Dormer monument. Lower Right: Lord Dormer and his wife, Elizabeth Browne. It is interesting to not how within the space of one generation the fashion for recumbent figures had been replaced by one of kneeling figures. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The monument to Sir Robert Dormer (d.1552). This monument was described by Pevsner as “the finest monument of its date in England and of an unparalleled purity of renaissance elements”. He made comparisons with Italian monuments. The sarcophagus at the centre is dwarfed by its grandiose surround. It is of local stone. The canopy is supported on paired corinthian columns at the front and and two pilasters at the back. It really is very avant-garde. Its classical elements make the later Dormer monuments in the chancel look somewhat provincial and retro. The family fortune was made in the wool trade. Like Sir William and Lord Dormer, Sir Robert was an MP and Sheriff as well as holding other posts without making any indelible mark on our history. Right: The extraordinary motif of a ram or goat on the front of the sarcophagus, matched by others at the corners. I have to assume that they are rams, given the the Dormer wealth came from the wool trade with northern Europe, |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Superb Corinthian capital on the Sir Robert Dormer monument. Right: Brass commemorating Harry Blackwell (d.1460) and wife. The brass is another gift to the costume student. Probably Blackwell was a prosperous wall merchant. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west. Note the extraordinarily high tower arch that reaches right to the rafters of the nave. Centre and Right: Respectively, the south and north doorways to the putative former pre-Conquest west gallery. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Left: To the north of the altar is this blocked pre-Conquest doorway. I assumed initially that it had given access to the crypt or possibly to an ambulatory to the crypt but it was more prosaically a door to the outside in a somewhat unusual position at the junction of the chancel and the north aisle. This is proof that he aisle itself dates from the original church. Centre: Wall monument Henry Fynes (d.1758). It is an odd combination with a fat cherub removing a drape from an urn while an especially grim skull is at the foot of the tablet. This has been attributed to Louis Francois Roubillac (1702-1762), a French Huguenot sculptor working in England. He carried out many prestigious commissions for th great and the good but there are several examples of his work in rural parish churches. Right: Monument to Lady Sophia Dormer (d.1695). |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Left: Looking towards the east end of the south aisle with a simple parclose screen. Right: In a church of many treasures both in architecture and furnishings, this wonderful piece of fourteenth century stained glass in the tracery of the south aisle window is easily overlooked. It represents the Coronation of the Virgin and the crown on Mary’s head is clearly visible. A wonderful piece. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This is not a church endowed with fabulous woodwork, but it certainly has its moments! I love this poppy head (left and centre) with the most wicked-looking monsters just waiting to nip you in the butt! Whereas on the right we have a somewhat camouflaged lurking green man. These poppy heads are clearly of quite different vintages. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another little joy: two tongue-poking heads on the cusps of the rood screen. Right: This is surely the base of a Norman (not pre-Conquest) font. It is quite clearly of the “Aylesbury School” and a particularly nice example. Have a look at the base of the (complete) Aylesbury font at Great Kimble and you will readily see the design similarity. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

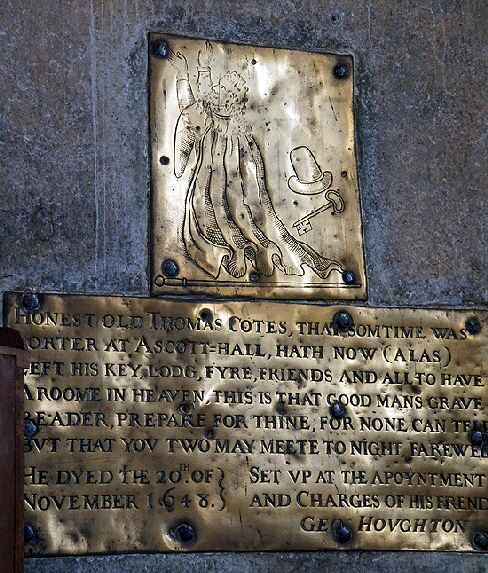

Left and Right: This is surely one of the most interesting - and moving - brasses you will see in any English parish church. It is to Thomas Cotes who died in 1648, the porter at Ascott Hall. Brasses were invariably for the rich but here we have a brass to a humble man. The inscription shouts out his popularity. This was clearly a man who liked to share a flagon or three of ale with his mates and one George Houghton was moved to pay for this monument. His key is shown next to his hat with a staff of office beneath him. The inscription ensures that nobody should forget his or her own mortality: “None can tell but that you two may meet tonight....” Brrr. Get that barrel open, Tom. Another truly wonderful treasure of this church. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A bit of a miscellany here. Left. A rather surprising rood loft entrance from the south wall onto the parclose screen in front of the south chapel. Centre: A pillar piscina near the altar. Although hardly unique, this is quite a rare furnishing. Presumably cutting a normal piscina (and sedilia) into the polygonal wall of a pre-Conquest chancel was (thankfully) seen as being a bit too much of a challenge. Right: The corbel on the respond of the arch from the south chapel to the chancel. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the risk of repeating myself, it is much darker in Wing Church than my Photoshop-enhanced photographs show - and the sun was beginning to sink on the afternoon in January 2024 when I took these pictures. So apologies for the graininess of these which were taken using a ludicrously high ISO setting (for the photographic cognoscenti amongst you) which comes at the cost of grainy images. You can see that the female figures (left and second left) are not obviously the usual angels - they have no wings! Perhaps that is St Mary Magdalen on the left with her pot of unguents? The men, on the other hand, are grim-faced coves blowing into didgeridoo-sized instruments. In fact the guy second right looks like he might be eating his. What fun, though, eh? |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The addition of a Perpendicular style south porch is, with the west tower, the most obvious alteration to the Anglo-Saxon fabric. The iconoclasts got to the statue in the now-empty niche over the doorway, leaving it looking a little forlorn. The door itself has lovely hinges. For the Church Crawlers amongst you, we can see the most welcome words in the English Language in this picture: “Church Open”. Thank you to the Churchwardens and PCC of Wing Church. Centre and Right: Angel carvings in the spandrels of the south doorway. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north east. The gothic windows, though inevitable and necessary, are sadly incongruous and somewhat random. Again, you can see the top of an arch of the crypt beneath the chancel. The whole of this north side (apart, of course, from the north porch) is pre-Conquest masonry. Right: The south clerestory. On both sides of the church the westernmost window has been altered. perhaps that has something to do with the date “1649” picked out in ironwork just below the parapet. Or it could point to some slight raising of the clerestory itself. Who knows? This wall, by the way, is not pre-Conquest, |

|

|

|

|

Left: The west door. It is late Perpendicular in style and looks contemporary with the south porch. Centre: Looking through the lychgate to the south east of the church. Right: The tower - unusually - looks all of a single date. The Perpendicular west window is a noble one, reflecting the nobility of the tower arch within,. |

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Two views of the somewhat waterlogged crypt, the pictures taken by poking my ultra wide angle lens between the iron railings! Today It is hard to imagine the veneration and awe that would have been inspired by the contents of the inner sanctum here in the first millennium. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Left: The church from the north west, Right: I wonder how many people spot this little chap, arms outspread, sitting at the gable of the east wall of the nave? He must have been put there when the parapets were installed, probably in the fifteenth century. |

|

|

|

Left: Tenth century stonework underneath the roofline of the apse. Right: A badly weathered animal figure - a goat? - in the south porch frieze. |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Three Pictures Above: Wing is not a church with a host of grotesques, but this being Wing the ones they do have are entertaining..Right: .I almost missed this one out. Remember that blocked pre-Conquest door leading from the north side of the altar? This is where it emerges on the east end of the north aisle, proving the aisle’s Anglo-Saxon provenance. |

|||||||||

|

This page, written in February 2024 is one of the longest I have written for any parish church. For any seasoned church crawler the motive for visiting it must be first and foremost its antiquity and its importance within the context of English pre-Conquest architecture. Yet, it has so much to offer inside as well as outside that it must be amongst the contenders for the the most interesting church in England. It is a must-visit church. And it is open. Just do it. |

|

I hope you have enjoyed this Page and, perhaps, many more besides. Could you help me to make it better still and preserve its future? |

|

|

|