|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am coupling these two very different churches because between them they have many of the misericords that were located in nearby Fotheringhay Church before the Dissolution of the Monasteries meant that that unfortunate establishment had no further use for them. Others are located at Tansor. I am going to start with Benefield.

It is one of the joys of church crawling that no matter how anonymous a church is within the various gazetteers it might still thrill and amaze you. All writers have their preferences (Simon Jenkins’s boat is easily rocked by monuments, mine by Norman fonts) and corresponding blind spots (church carvings and monuments respectively). And let’s face: there are so many parish churches in England that some are bound to slip under the radar.

My visit to Benefield Church was for one reason only: the misericords. I had already visited Benefield, found it locked, photographed the exterior and never expected to return. Serendipity is a big part of church visiting. I had visited Tansor Church because it was Norman, seen its misericords, also from Fotheringhay, and from its Church Guide found there were others at Benefield and at Hemington. So here I was again!

The church is enormous, and impressive. You can tell immediately that much of it had been much rebuilt during the Victorian period because everywhere you see Anglo-Catholic imagery that would never have survived the mediaeval

period.

|

|

|

|

|

The original church was fourteenth century and probably replaced an earlier one. Of the mediaeval church only the chancel is substantially intact, albeit altered, a and probably the lowest stage of the west tower..

The whole flavour of the church was dictated by the tastes and beliefs of the local Watts-Russell family. The nineteenth century saw the “Gothic Revival” in architecture, one of several movements that looked back nostalgically to the pre-industrial mediaeval period when, so it was felt, true craftsmen produced artefacts of great beauty impelled by almost mystical pride. This same rose-tinted nostalgia gave us the Arts & Crafts movement that produced output of stunning beauty at preposterously unaffordable prices!

1833 saw the birth of the Oxford Movement at Oxford University (where else?) which through a long series of ninety pamphlets that, two hundred and fifty years after the Glorious Revolution, promoted the notion that the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches should draw closer together. That Benefield Church was restored in 1846-7 in such blatantly Anglo-Catholic style would seem to suggest it was tapping into that new seam of religious thinking. The Church Guide quotes Goodhart-Rendell describing it as “an important specimen of the sumptuous Tractarian church”. To complete the historical context it is pertinent to observe that the Robert Peel’s Catholic Emancipation Act which removed the final institutional sanctions against Roman Catholics in public life (though not in affairs of the Crown!) was passed only in 1841.

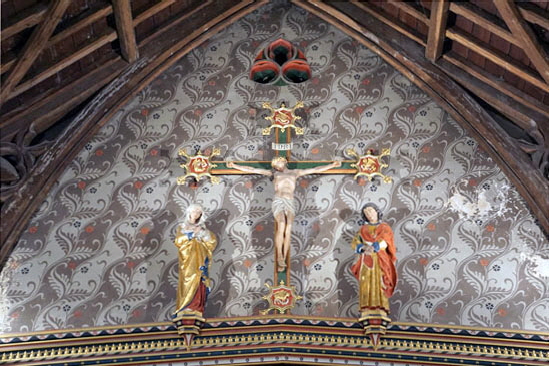

The nave is dominated visually by its screen and rood loft which are, in contradiction of mediaeval practice, separate. The screen is topped by course of wooden panelling with some carved symbols of the passion. A few feet above that, physically separated but very much part of the same artistic composition, is the beam of the rood loft topped by the most blatantly conspicuous rood (cross) and supporting figures that you are ever likely to see in a church still dedicated to the Anglican liturgy! If the Watts-Russells wanted to make a “statement” they couldn’t have found a more “damn you eyes” way of making it. It is all quite lovely. Does any English parish church have a finer delineation between nave and chancel?

The spandrels between the nave arches are decorated with over-sized religious carvings in stone. Fascinatingly, this is something you would not have seen in a pre-Reformation church where such carvings would have tended to be faces or grotesques.

In a further reversion to pre-Reformation practice, the Watts-Russells built themselves a private chapel north of the choir in what is now the space housing the vestry and the organ. It was carefully designed to allow the priest to move freely between the hoi polloi and patrician classes even during the services in the main chancel. This area got its present use when the Watts-Russell family built another private chapel in 1925 on the side of the north aisle to commemorate Capt. Arthur Egerton Watts-Russell of the Coldstream Guards (of course!). The furnishings are in baroque style and, once again, it has distinctly Catholic flavour.

The chancel too is of great beauty. The east window is a copy of a window in Ely Cathedral and depicts John the Baptist and the four Evangelists. In 1897 the renowned Sir Ninian Comper installed today’s stunning altar and reredos, incorporating the altar of 1851. Amongst all of this lavish modernity sits with almost touching incongruity the five mediaeval misericord-equipped stalls from Fotheringhay Church. One imagines that the Watts-Russell family may have cherished them as symbols of a pre-Refomation Roman Catholic England because they were actually brought from Tansor Church (which still has several) in 1899: they are not here by historical accident.

It is interesting to study the Fotheringhay misericord diaspora. Can it really be a coincidence that those at Tansor so strongly show the symbolism of the House of York; that the most roguish and entertaining ended up at isolated Hemington; or that those at Benefield are the most innocuous? I can't help feeling that all three churches chose their Fotheringhay legacies carefully. Tansor that once had them all perhaps liked the vague prestige of the Yorkist connection. Faced with a choice, the Watts-Russells perhaps went for what was "safe" for Benefield, leaving Hemington with the tabloid stories!

Also worthy of note is the elaborate balanced wooden font cover that covers the Caen stone octagonal font. It is not unique even to this area, nor is it the finest (see that of Ufford in Suffolk) but it is a very fine one and is topped by a fine naturalistic carving of a Pelican in its Piety (the Church Guide mistakenly designates it as a “Phoenix”). In a church that has sought so hard to recreate a rather idealised religious and artistic reflection pre-Reformation times no symbol could be more apt. Except, ironically, a phoenix!

It is a fascinating church with its roots in the patrician instincts and, dare I say it, muddled religiosity of a local family that was rich but by no means aristocratic. As you peruse these pages you will see I have an instinctive dislike of parish churches that were treated by the rich as personal fiefdoms and private mortuaries. Yet when you see Benefield Church it is impossible not to admire the beauty of what was created and to not respect the good intentions of those who commissioned it. Nor would it be fair to suggest that they sought to dominate it. Whatever your views about Anglicanism versus Catholicism, of the rich versus the humble, there is no disputing that the parishioners of Benefield have a church to be proud of and which will still be a thing of wonder long after the Watts-Russells have faded into obscurity. Do visit it (you need to phone first) because it is quite beautiful and very unexpected. Not that it will be unexpected to you any more, when I think about it!

|

|

|

|

Left: The rood (the cross) flanked by Mary and maybe Joseph? Each of the four arms of the cross has the symbol one of the four Evangelists. Centre: Curiously, the centrepiece of the gallery is the royal coat of arms. The display of a royal coat of arms was compulsory in the post-Reformation period to demonstrate the primacy of the monarchy in the Anglican Church. Were the Watts-Russell family earnestly professing their Anglican loyalties here in spite of their obvious Roman Catholic leanings?

|

|

|

|

Left: The arms of the Watts-Russell family - presumptuously supported by a trio of angels! - is to the right of the royal arms. I don’t know how these arms were derived but we can see white roses of the House of York and Scotland’s rampant lion. Also, interestingly, there is a bishop’s mitre. I can’t find out much about the Watts-Russell family but see the footnote below. Right: These are the arms of Peterborough Cathedral, the left side of which is the arms of the Vatican. Note the large bishop’s mitre. There are angels again but possibly with somewhat more legitimacy!

|

|

|

|

Left: The font is of Caen stone which is particularly conducive to decorative carving. It has symbolic carvings of the Evangelists on four of its sides. The huge font cover is removed by use of an elaborate system of pulleys. Centre: The font cover is crowned by this Pelican in her Piety, an ageless and ubiquitous piece of Christian iconography. The chicks really are quite charming sitting on their nest of sticks! Right: The north aisle with its own mini-screen and a Watts-Russell hatchment board to the left. Beyond the screen is the organ and vestry and just visible to the left is the Watts-Russell memorial Chapel.

|

|

|

|

Left: The entrance to the Watts-Russell on the north side of the church. There is a baroque feel to the whole thing, and see yet another set of arms for the family! Right: The spandrels to the arcades have biblical figures, something I have never seen in a mediaeval church. This one, of course, is Moses with his tablets.

|

|

|

|

The Victorian woodwork shows further evidence of Watts-Russell hubris with more family symbols.

|

|

|

|

Near Right: The Victorian stalls show carvings that certainly stand comparison with the fifteenth century misericords. I don’t, thougk, know what this skull-bearing gent is supposed to represent unless it is a reference to the inevitability of death that was also such a perennial in the mediaeval period. Far Right: A very pretty carving of a bear and a monkey amongst foliage. Again, such a carving would not have been out of place in a mediaeval church.

|

|

|

|

Left: The church was rebuilt from the ground up but it is a bit of a challenge to know what is ancient and what is Victorian. I had thought initially - perhaps hoped - that the little vestibule on the corner between the north aisle and the chancel might be mediaeval but apparently not.. It is splendidly rib-vaulted and has nice carved bosses. Centre: A green man carving inside the vestibule is a something of a surprise. Perhaps the sponsors thought it was ok to have a pagan symbol in such an obscure corner. It is rather “grown-up” in appearance as befits a Victorian pastiche. Right: This is the altar in the Watts-Russell Chapel. It would not look out of place inside an Italian baroque cathedral. I hate to use the word “ugly” but,,,,well, you know...it’s a bit...isn’t it?

|

|

|

|

Top Left: A roof boss carving of a bishop from the north east vestibule. If you compare it with the green man in the row of photos above, you will see that they were almost certainly carved by the same mason - look at the eyes. It is a more naturalistic face than you would see in most mediaeval churches. On the whole, perhaps surprisingly to our modern thinking, bishops were not then a particularly popular subject matter except when they were being lampooned on bench ends and misericords! They were not especially popular public figures and were more likely to be despised for their acquisitiveness than respected for their often dubious piety. In the twentieth century a fair number of town churches acquired little carvings of bishops. I think it was seen as somewhat “right-on” to depict the local Bish. This carving, of course, is quite respectful and note that he has vestiges of gold paint on his mitre. I think it is one of history’s little contradictions that during the mediaeval period when everyone was scared to death of damnation our churches were treated as working buildings and the masons and carpenters had robust and distinctly undeferential attitudes towards decorative carvings Today when Christianity is no longer a major social force everything is much more well-mannered and the dwindling numbers of parishioners wouldn’t dream of showing disrespect to a bishop. A question for you: do you know the names of yours? Other Pictures: Roof bosses from the chancel roof.

|

|

|

|

Left: This splendid tree next to the lych gate is much older than the church itself. Right: I’m not much of an enthusiast for churchyard furnishings and inscriptions but sometimes they jump out at you. Luciana Baker lived to be 104 years old an was a widow for the last forty-three of them!

|

|

|

|

|

Hemington

|

|

|

|

Dedication : SS Peter & Paul Simon Jenkins: Excluded Principal Features : Splendid Misericords from Fotheringhay; Curious Font

|

|

|

|

|

|

I suspect that the sleepy little village of Hemington will be as surprised as anyone to see their church being “bigged up” on a website! Architecturally it is, to be polite, unexceptional. Damning with faint praise? That’s not my intention because it’s not at all ugly merely - unexceptional! The west tower is in original Perpendicular style . The rest dates from 1660 and it was, as pevsner puts it, “gothicised” in 1873. But the building itself is not what we are here for.

As mentioned previously, Hemington acquired a large share of the misericords that became redundant in Fotheringhay Church after the College was dissolved. They came here, it is said, via Tansor but it seems that they were never actually in Tansor Church. Tansor has Fotheringhay misericords of its own and they are all decorated with the symbols of the House of York. Benefield, on the other hand, acquired three rather unchallenging examples, almost as if the Watts-Russells didn’t want to offend anyone. One way or another, little Hemington has ended up with what must be one of the most vibrant collections of mediaeval misericords you will find in any small parish church in England. The carvings are elaborate, the quality what you might expect of a church endowed by a Royal House. It is just one of those endearing quirks of English history that some of the most rampantly hubristic misericords in England have ended up in a village with a population according to the 2011 Census of...wait for it...257 souls! Edward IV must be raging in his heavenly palace.

We are going to be looking at the misericords in some detail. Hemington, however, has a couple of other little gems. The first is its font that is reckoned to be maybe late twelfth century. Reckoned by whom you might ask? I’ve no idea! It is clearly no later than that but it could just as easily be older. It is square in plan with four chamfered corners each bearing remarkably crude - almost spooky - heads. It is a triumph, if that is the word, of simple folk art.

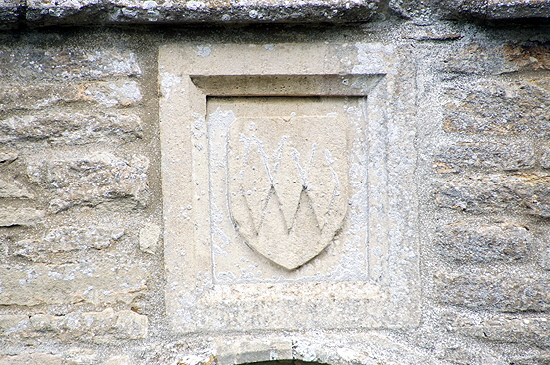

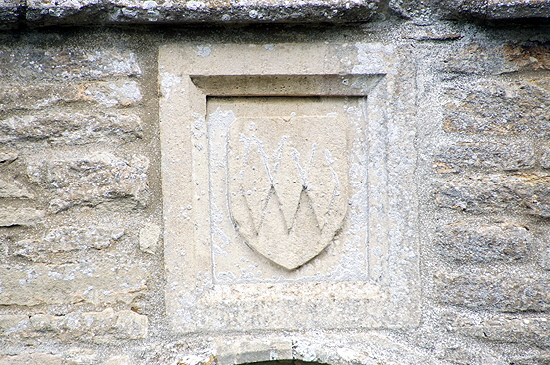

The other little gem is a brass of Thomas Montague and his wife, dated 1517. It is very fine, has excellent costume details and some very intricate coats of arms. The Montague Arms can also be seen carved over the west door. Montague is an illustrious family name, of course, but it seems that Thomas was a commoner and an ancestor of the more aristocratic Montagues. Anyway, it’s an exceptionally fine piece.

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The round-headed south doorway is in Transitional style but is seventeenth century. Centre: The east end and chancel. The misericords are situated to left and right. Right: looking towards the west end.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. The chancel arch is rather a grand one and incorporates some stones from an earlier incarnation. Right: The Montague Arms over the west door.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Royal affiliations don’t get much more blatant than this. The supporter (the right hand one having been lost) also shows a crown and it has two ostrich feathers, symbols of the Yorkist kings. Right: A crowned lion that, I suppose, needs little explanation. It’s a magnificent bravura carving. Don’t mess with me, sonny!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: This one is very much of a series with the misericords at Tansor. The fetterlock and falcon are both symbols of the House of York. The falcon shown here is almost identical to the one in the ceiling in the west tower at Fotheringhay. There is an almost identical design at Ludlow in Shropshire where Richard Duke of York, father of Edward IV and Richard III, took over the castle in 1425. More about that in the footnote below. Right: Now this is what I call a dragon! Big, ferocious and up to no good. Note the vibrancy of the supporters. You wouldn’t want to meet these three day on a dark night. Or in the daytime, come to that! Edward IV used a dragon as his symbol of his Earldom of Ulster.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: It is tempting think that these two wild boar are also Yorkist symbols since the wild boar was a symbol much favoured by Richard III. He wasn’t born until 1452, however, which is a bit too late. The boar was a popular misericord device. Note the acorns on the supporters. Right: Now for the fun stuff. A man with his ale is also an enduring theme for misericords. This chap is happily holding up his flagon. Presumably his other hand once held a another containing wine. The supporters are ale barrels and a wine jug.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two more hardy perennials of the misericord world. Left: A mermaid struts her stuff. The mermaid is a popular mediaeval theme. It is said to be allegorical: the mermaid is voluptuous but sexually unavailable. It all shows the (alleged) futility of lust. Luckily for all of us it seems that lust occasionally was not futile at all. I am always amused by the ubiquity of the image (see, for example, a Norman tympanum at Stow Longa in Cambridgeshire. Allegorical it may be but there are few allegorical scenes on English misericords. Could it be that our naughty stonemasons and carpenters quite liked an excuse to carve even half a woman with nice little attributes? Note, again, the flamboyant supporters in the form of fish. Right: Well I don’t know why this chap in standing on his head but it takes all kinds to make a world as they say!

|

|

|

|

Left: A man’s head with the body is another popular mediaeval motif. The craftsmen of the day loved these hybrid creatures and the notion of a “world turned upside down”. Right: The owl is another ubiquitous image. It did not, however, have the positive connotation of wisdom that it enjoys today: far from it. Because the owl is nocturnal In mediaeval iconography it was used often to denote the supposed ignorance of the Jews who avoided the light cast by Christ. Note the supporters that are normal - diurnal - birds. In many depictions the owl is mobbed by these birds that are allegories for Christians that live in the light. Anti-semitism, sadly, has been with us for many centuries.

|

|

|

|

Left: A fishy supporter on the mermaid misericord. Centre: The side of the stalls has this crown with an ostrich feather in the background. You can sense the insecurity of the Yorkist line that they felt the need to constantly proclaim their royalty. Right: Each set of stalls (two of five seats each) is finished with these elegant curved carvings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Upper Left: The rose of York appears on the side of a stall.

Lower Left: A close up of the Yorkist falcon.

Above: One of the fearsome supporters on the dragon misericord.

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The simple Norman font with heads at each corner. Note the original pedestal with pellet moulding. Centre: The Montague brass of 1517. Right: Montague’s wife..

|

|

|

|

Left: One of the heads from the font is showing a long tongue. It is actually quite unusual to have a facetious image on a font. Right: This would not look out of place on any of dozens of Norman corbel tables in the country.

|

|

|

|

Fotheringhay’s Retained Misericords

|

|

|

|

Not quite all of Fotheringhay’s misericords have been dispersed to Tansor, Hemington and Benefield. Two remain as exhibits. Both are badly damaged but we can see enough to see that they are of the same family and that they were as entertaining as th others in the series.

|

|

|

|

Left: A jester compete with bells on his hat. The bottom of his head and the bottoms of both supporters have clearly been deliberately sliced off. I can’t imagine why because there couldn’t have been anything to upset the iconoclasts. Right: A fine lady with a rich headdress, The remaining supporter is a man’s head in what appears to be an everyday (as opposed to aristocratic) headdress.

|

|

|

|

I find myself in the rather odd position of relegating the famous church at Fotheringhay - awarded three stars by Jenkins - to a footnote behind the most mundane of churches at Hemington. It is an absolutely magnificent sight and a gem of fifteenth century Perpendicular architecture with flying buttresses that everyone seems to recognise but which are actually quite rare on an English parish church. I find its interior, however, superb but not very interesting unless you have a particular interest in the Royal House of York. If you are near it you should certainly visit it - but be warned that at the time of writing (December 2017) it is under major restoration and you would be well advised to wait until it is finished, Much of the exterior is under scaffolding and tarpaulin.

Briefly, it was not begun until 1411 when a college foundation transferred from the castle. Collegiate status tells you why there was a need for misericords. Edward Duke of York who died at Agincourt in 1415 leading the English vanguard (which was very unlucky given the overwhelming English victory) was its patron. It was not completed until 1434. By 1455 the House of York was embroiled in the Wars of the Roses. In 1461 Edward IV became the first Yorkist king. So there is a a bit of a contradiction with these misericords: the closed fetterlock points to a pre-1461 date. Yet the various crowns and symbols of royalty suggest post-1461! The fetterlock emblem supposedly represented the House of York being locked out of the throne and was depicted as open after the accession of Edward. The Yorkists and Lancastrians both traced their line back to Edward III who died in 1377. So it seems that all the crowns and royal insignia represented their claims to the the throne rather than to any actual kingship. All this said, however, the carpenters of the day were as independently minded as the masons. It could just be that they were toadying to their patrons. And what a wonderfully covert place for sedition: under the seats of the clergy!

The Duke of Northumberland demolished the chancel after the suppression of chantries, colleges and monasteries leaving it with the odd proportions that it has today, At this point, of course, misericords became superfluous.

|

|

|

|

A Note about Access and Findability

|

|

|

|

Benefield. There is an Upper Benefield and a Lower Benefield and the church is in the latter village. You can usually spy it on a hill as you approach the village. Access is via a keyholder and you need to arrange this in advance. Use the “A Church Near You” website and contact a churchwarden. We were accompanied on our visit.

Hemington: It’s not too difficult to find. When we visited we found a phone number on the church door. The lady lives close by but the first time we visited she wasn’t at home. I rang her before travelling a second time and gained unaccompanied access

Fotheringhay: You can’t miss it because it is very large. Being a historical building it is open a lot of the time. As noted above. at the time of writing it is accessible but the exterior and to a slightly less extent the interior is marred by restoration work. Check the state of play before you travel.

|

|