|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

and this is believed to be thirteenth century. It is joined to the main structure by a corridor. Unusually, it has its own (empty) little bell cote and is has been suggested that it stands on the site of Eilian’s original cell. It is an odd-looking place. The nave and its battlemented clerestory threaten to overwhelm the tower. The battlements themselves are unusually hefty making for a somewhat unsophisticated look. The tower is rendered and looks incongruous next to the rubble stone of the rest of the church. Until comparatively recently it was painted dazzling white with limewash. Prior to that, it was covered in “modern pebbledash” so I will settle for the rendering! A thirteenth century document suggests that white lime-washed churches were common in Anglesey and so the twentieth century restorers were spot on, it seems. As an aside, the church of Llanfechell, just a couple of miles south of Cemaes, is also of Romanesque origin and is still painted white from end to end. In truth, however, it is the treasure house of unusual fittings and artefacts which repay a visit to this church, especially the totally unexpected rood screen. Let’s take a look. |

|

|

The nave is dominated by one of the most extraordinary rood screens I have ever seen. It is perhaps the only one I have seen that adequately demonstrates the full function of these structures. Chancel screens were not entirely outlawed by Reformation and Commonwealth and so many churches retains quite substantial fragments. Sometimes those fragments were hidden away by parishioners waiting for the iconoclastic storms to pass. The rood (cross) from which the structure gets its name and the supporting wooden sculptures of Mary and St John was a definite prohibition; so any you see now are going to be Victorian Anglo-Catholic replacements. At some you will see the defaced images of saints painted on the lower panels. Some are very beautiful and lavishly painted, whereas this at St Eilian’s is beautiful only to those who understand its rarity. What makes it stand out is that is has retained the wide balcony area - the “loft” that would have allowed the priest to conduct parts of the liturgy from this elevated position. The balustrades survive - a rarity indeed. Moreover, visible to the right, is the door which still gives access via a stairway from the chancel. In countless English churches we see an empty doorway marooned near the chancel arch with no apparent function, the screen, or at least its loft, having long disappeared. If you imagine the screen chopped off at the lower course of carved decoration, that would be the norm for most church screens today. How many rood screens across Great Britain were just like this? Not lavishly painted and gilded, not with the finest standards of carpentry and wood sculpture, but rustic and functional? |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Decorative carving on the west side of the screen. Right: The underside of the screen as seen from the chancel. The decoration is slightly less lavish and we can see saltire crosses. Were they once painted? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The painting of the Grim Reaper in the middle panel of the screen is perhaps the most striking thing here. Although he clearly had never read “Gray’s Anatomy”, the painter had a modicum of knowledge of the human skeleton, at least , although those arms are of gorilla-like length! The words that emanate from his scythe are “Colyn angau yw pechod” - “The sting of death is sin”. Reminders of mortality are, of course common in churches, as are reminders of the price of sin in the afterlife. A “doom painting” would be the more usual aide memoire (see St Thomas, Salisbury for a magnificent example) but there would have been no escaping the bluntness of this message to the unwashed sinners in the congregation. Was this image accompanied by others that were removed during the Reformation? Centre: Screen doors are another rare survivor, although it is impossible to know if these are original. Right: the church looking to the west. The original tower arch would have been Romanesque, of course. I am nervous of saying “Norman” here lest someone remind me that this area defied Norman occupation. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The east end. The east window is reminiscent of that at Llanbadrig. A typical thirteenth century triple lancet window arrangement - the very epitome of the “Early English” style - sits within an arched recess in a fifteenth century chancel. Elaborate window tracery is rare on the island, as is fine stone, and we might presume that fashions of English mediaeval architecture found their way to Anglesey rather late, if at all. Right: The screen from the east. The chancel has seating on three sides which can be dated to 1533. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The fourteenth century south-east facing St Eilian’s Chapel. Why, one wonders, would it have had this orientation? Was the original building (if indeed there was one) east-facing? The chapel pre-dates the existing chancel and nave. One might speculate that there were architectural reasons but this makes no sense because the passageway to the chapel from the nave is later than the chancel itself so it seems it was built to stand alone. A mystery. Right: The altar is in fact a wooden shrine. The Church Guide recounts that the timber panels to left and right were at one time removed. By squeezing through the space that was left the parishioners could, they believed, be cured of illness! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

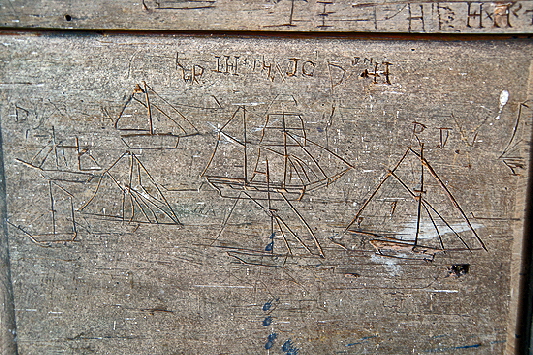

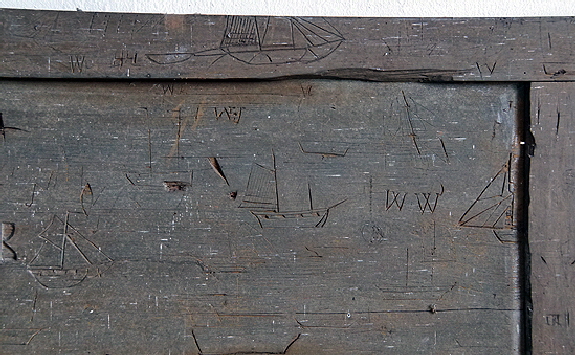

Left and Right: Many churches make much of their graffiti. Perhaps because these examples at Llaneilian are in wood rather than stone they seem to be unremarked upon, even in the Church Guide. But someone has gone to considerable trouble here to depict all manner of sailing vessels that he must have seen from the island. The details of the sail arrangements are clearly meant to be accurate. They are nineteenth century, it seems, and carved into a timber panel that is hanging on the wall. It was a cupboard door that was removed from the vestry in 2002. That begs the question: who had the temerity to leave his doodles in a vestry? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chapel is full of all sorts of interesting odds and ends, amongst them this ancient font that I presume was of the original Norman church. Right: The chapel looking towards the west. the door to the left leads to the passageway to the chancel. The door to the right leads outside. Why would this tiny place need two doors? My guess is that the left hand door was the original and only doorway. Once a passageway was built from the chancel, however, that meant that access would probably have been restricted to the clergy. Thus, another door would have been needed for the common people. Unless, of course, you know otherwise? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chapel has a number of wooden timber trusses carved with foliage. Centre: An ancient door preserved in the chapel. Right: This chunky poppy head within the chancel looks later than mediaeval but imitates some here that do seem to be mediaeval. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

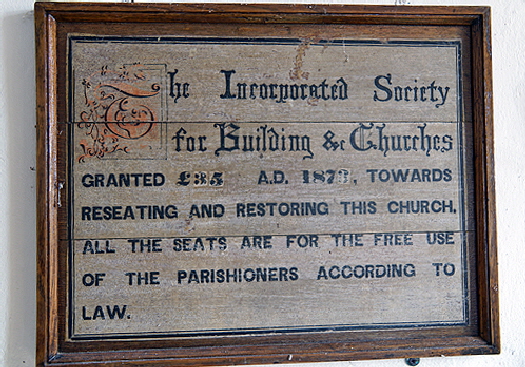

Left: Still in the chapel is this lovely solid oak chest dated 1667. That is, from the year following the Great Fire of London. It is liberally studded with nails! You can see, if you look carefully, slits in the top which would, according to the Church Guide, have allowed pilgrims to the shrine to deposit the usual offering of a groat. This gives us a flavour of the financial advantages accruing to a church from an association with a saint, however obscure. It is remarkable to consider that this was going on for over a thousand years for a saint who might never have actually been here! In post-Reformation England, such a shrine would have been an unlikely survival indeed. Love him or loathe him (and Hilary Mantel has not quite rehabilitated his reputation!), such shrines were considered by Thomas Cromwell to be idolatrous rip-offs that took from the poor to enrich the Church. And, you know, perhaps he had a point? But he rather spoiled things by giving or selling the proceeds of Dissolution to the the even richer didn’t he? Right: Another exhibit giving insight into Church affairs. The words ”for the free use of parishioners according to law” is a swipe at the old environment where pews were allocated according to social rank or status, an unedifying and, dare one say it, ungodly feature of post-Commonwealth society. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The chancel has these four highly-painted musician carvings. Curiously, the Church Guide identifies then as two pipers, clearly correctly and two “trumpeters”, clearly wrongly”! The trumpets are obviously reeded woodwind instruments. They carvings are obviously of much more recent vintage than the chancel itself. So why are they here? Well, here’s another piece of speculation for you. I am guessing that the church used the top of the old rood screen to house a small orchestra that would, in most churches, have been located in a purpose built west gallery. Such galleries gave their name to a genre of sacred music - “West Gallery Music” - that enthusiasts keep alive to this day. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Second Left: Two more figures within the nave in much the same style as the musicians. We must presume that all of these date from a time when roofing work was being carried out, clearly in the post-mediaeval period. Second Right: One of the original bench ends and poppy heads. See the more modern version earlier on this page. Right: The ironwork on the south door here really caught my eye. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: I have no idea how old is the is ironwork on the south door. Perhaps not very old but striking nevertheless |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south east of the church showing the passageway from the chancel to St Eilian’s Chapel on the right. Note the tiny, empty bell cote on the chapel hinting at a building that was to some extent independent of the church until the passageway was built. Right: The church from the north east. The spire is an unusual feature for an Anglesey church. Note the chunky battlementing. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The monolithic Norman tower. Centre: Ancient the tower might be, but not the most ancient structure here. That accolade goes to this ancient cross shaft in the north west of the churchyard. Possibly it was a “preaching cross” - a place at which people might assemble to hear the word of God before a church was built here. Right: Church and Churchyard cross in the morning sunlight and shadows of a fine Summer’s day during the heatwave of August 2022.. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - Those Pesky Saints |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Both St Eilian’s and Llanbadrig up the road in Cemaes have legendary associations with saints. We have all heard of Patrick but few of us know of Eilian. How plausible are these connections with Anglesey? For a start, there is actually no evidence that Patrick was shipwrecked at all, let alone in Cemaes Bay. Indeed, Patrick’s history is shrouded in mystery. We know he was of a Romano-British family and we know from his own account that he was kidnapped by pirates and enslaved in Ireland. Many scholars believe he was actually from Dumbarton in modern Scotland, a historically important fortress town. So he was not, in fact, Irish. We know he escaped his enslavement in a ship but we do not know where he escaped to. On a prosaic level the “island” of Middle Mouse in Cemaes Bay is so tiny that you would have to say it would have taken considerable skill - or monstrous bad luck - to have hit it at all! We know Patrick returned to Ireland and was responsible, at least in part, for the Christianisation of Ireland. In a model that others were to later follow, Patrick recognised that if you converted the kings the commoners would follow. Everything else about his life is pretty sketchy. This is, to say the least, unsurprising. The whole history of these islands is shrouded in mystery from the departure of the Romans in AD410 until about AD600, and we don’t know a great deal after that either! I hate the term “Dark Ages” which has undercurrents of an ignorant, uncivilised population. We know enough to refute that notion. But as applied to the notion that we are groping in the dark for knowledge, it is accurate. Most of the chronicles we more or less rely upon were written centuries later. Remember the speculated date of Patrick’s supposed arrival in Cemaes is just forty or fifty years after the legions departed. And there were no Plinys or Tacituses left to record things. I think we would have to say, sadly, that Patrick’s association with Cemaes is probably fanciful. I have found not a single academic reference to it. Patrick existed, however, even leaving his own very brief semi-biography - his “Confesio”. He called it that because he was not always a good boy, it seems. I am afraid he said nothing about ridding Ireland of snakes either. So what about Eilian? Well, let’s start with the stuff about the oxen and blinding Cadwallon Lawhir. It didn’t happen, did it? Even if you do believe it you have to question why blinding a bloke for wanting your oxen (which he had strangely decided to ship across the Menai Strait) and then giving him his sight back would qualify you for sainthood. Whereas those other early Christians were all doing stuff like resisting the sexual advances of pagan kings, converting people they shouldn’t, refusing to renounce their faith and dying horribly inventive deaths as a result. That stuff too is mostly baloney, of course, but at least what they did was, if true, laudable. If suicidal. But I have a problem with the whole story of Eilian. The first half of the fifth century was just horrible for Rome. Italy was ruled by the Visigoths from Ravenna and they espoused the Arian form of Christianity that held Jesus was subordinate to his Father, although also (in a way completely alien to Catholicism before or since) tolerating the indigenous version that held Father, Son and Holy Spirit to be be three individuals in one substance (no, I don’t get it either). Rome the city was in dire straits. Christianity was in the midst of endless doctrinal arguments. Yet we are to believe that the Pope (which one is not specified) decided amongst all this that it was Very Important to send someone to Anglesey - at the very edge of the old Western Roman Empire - to convert the Kingdom of Gwynedd to Christianity. He did this some one hundred and fifty years before in AD597 Pope Gregory decided to send St Augustine to Kent to begin the task of bringing “England” (which did not exist politically at that time) to Christ. Augustine was sufficiently intimidated to turn back before being exhorted by the Pope to resume his mission. But Eilian went undaunted to the edge of Europe to mess with the King. When I Google St Eilian (try it!) all I get is references to the church and almost word-for-word accounts of the Ox Incident. It seems that the Welsh monk, Nennius, mentioned Eilian in his “Historia Brittonum” some four hundred years later. Nennius seems to imply Eilian was Welsh, which is probably more plausible! So, I conclude that Eilian either did not exist or that his “story” is hogwash. But is there a more plausible story? “Welsh” nowadays means of the modern Principality of Wales. In the first millennium there was no Wales, there was no Scotland, and the shaky concept of England only emerged in the ninth century. The Britons of the Roman era spoke a Brythonic Celtic language. When the Anglo-Saxons invaded they called all foreigners and, therefore, all Britons “wealsc”. Many wealsc migrated west, keeping their Brythonic language. Others stayed, assimilated the Germanic languages of the invaders and in time spoke what we now think of as “Old English”. So it is eminently possible that there was an Eilian, that he was a Christian and that he migrated to Anglesey (Ynys Mon) from somewhere in modern England or in modern Wales. Or even from somewhere in modern Scotland. He might even have taken some oxen with him! It does not seem very likely he met the King of Gwynedd let alone had the bizarre encounter attributed to him. But he might have been an ascetic Christian who went quietly about his business spreading the word of his God. He probably preached - maybe from the site of the church - and converted some of his neighbours. There is a sacred well just half a kilometre from the church. If we know anything about the early Christians it is that they liked to appropriate Pagan sites; and Anglesey, formerly ruled by Druids, would surely have had copious quantities of those. My guess is that Eilian lived a holy life and died a venerated figure and was sanctified by the locals after his death. Indeed, it is a little know fact that “Saint” Patrick was himself never sanctified by the Roman Catholic Church, although it recognises him as such. A shrine might well have been created in Eilian’s honour and pilgrims may have travelled to the site. A little chapel might well have been erected. And then, probably, simple veneration became a profitable cult. The back story about Rome, Cadwallon and the oxen would have been good business. Yes, that might seem cynical. But remember that Eilian seems to have been good business for a thousand years, as the big bound chest in the Chapel attests. Finally, Cemaes and Llaneilian are only eight miles apart and Patrick’s shipwreck and the arrival of Eilian were purportedly only a decade apart. If Eilian came from Rome and Patrick from Ireland any encounter between them would have been “interesting”. Patrick would have been a Christian of the Celtic tradition and Eilian, by definition, an adherent of the Roman tradition. They would have had different tonsures (monkish haircuts), would have calculated the date of Easter differently and had many liturgical differences. Eilian would have believed in a structured and hierarchical church and Patrick in the simple spirituality of the Celtic tradition. These matters were not to be settled until the Synod of Whitby in AD664. Patrick’s native tongue was Brythonic Celtic and in his own “Confesio” admits to a poor standard of written Latin and that it was a “foreign language” to him. If sent from Rome, Eilian, we must presume, would have spoken Italian and Latin fluently. In fact, one wonders how an Italian priest would have managed in Ynys Mon at all. Of course, the notion of such a meeting is fanciful, but the contradictions of these two little legends - and I am sure most people see them as such - is manifest. That said, literature about these two churches does seem to talk about them as fact. Even today, such things grant kudos! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||