|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tettenhall and Wolverhampton. Gnosall was not listed and there is good reason to suppose that it had become an offshoot of the larger Penkridge. An MPhil paper by Anne Elizabeth Jenkins at the University of Birmingham in 1988 postulated that this area was the very heartland and stronghold of the ancient Kingdom of Mercia and the royal connections dated to that period, although exact dating for the foundations is impossible. It is also likely that these were Anglo-Saxon minsters where secular (that is non-monastic) canons would administer (as the word implies) and support the spiritual need of the locality. Despite its omission from the 1295 list, Anne Jenkins points out that Edward I (1239-1307) was trying to recover jurisdiction over Gnosall during his reign. It seems that it had been given to the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield in 1117 and Edward wanted it back! So, we can be sure that this small village and its rather oversized church had ancient origins. Nevertheless, we do not know the nature of the Anglo-Saxon building because the Norman one completely replaced it. As a minster church, however, it was almost certainly made of stone rather than the more usual humble wood and thatch. The core of the church dates from around 1100, quite early in the Norman church building era, presumably reflecting its exalted status. Its cruciform shape would have allowed the siting of extra altars, reinforcing its then collegiate status. The Norman crossing and the transepts remain and the south transept is perhaps the most interesting feature of today’s church. Aisles were added in the thirteenth century. During the same period an Early English triple lancet west window was installed. The fifteenth century saw the typical program of heightening the tower, modifying rooflines, installing decorative battlements and installing a clerestory. Thus we now see a Perpendicular skin but inside there throbs a Norman heart. |

|

|

|

Left: Looking east through the crossing to the chancel beyond. The one thing subsequent generations found difficult to remove was a Norman crossing, for which we Romanesque enthusiasts must give thanks. What a pain they must be for modern congregations, however, centuries after the physical separation of clerics and congregations was regarded as a good thing. As you see here, the only real solution is to move the altar from its customary place hard up against the east end. The original Norman roofline is very plain to see here. There is a nice symmetry between the aisles and clerestory. Note the substantial Norman opening above the chancel arch. I have seen it described as a “window” which what it is now, if it is anything. But what was it then? It is within the original building roofline. Was it a window from the ringing chamber into the nave? It seems very large for that. Its proportions suggest a doorway. But a doorway to what? Right: Looking towards the west with its triple lancet thirteenth century window, |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left Above: The west arch of the crossing, showing the three orders of geometric decoration. Left Lower: The chancel. The window is original and in the Decorated style. Right: Looking from the south transept through the crossing to the north transept which is completely filled by the organ. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Chancel arch capitals on respectively the north and south sides. These are strange freelance designs. The south side is quite inventive, the with looped “squares” formed from the various fronds of the design. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel looking though from the crossing, Norman arch overhead. Right: Looking from the south chapel into the south transept with the aisle beyond. You can see here the Norman windows at the higher level. The west window of the aisle is clearly an Early English lancet and it is customary to see the aisle as an Early English piece. Look, however, at the doorway from the transept into the aisle. It has a pointed arch flanked on one side by a round headed blind arch. This is a classic Transitional composition so the aisle seems to have been very early in the thirteenth or very late in the twelfth century. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

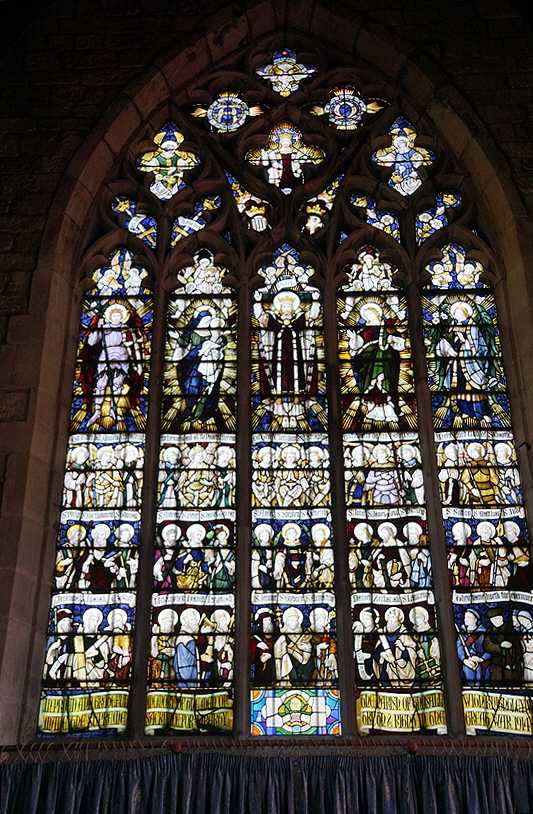

Left: Looking through the south transept to the south chapel. Right: The Decorated style west window. The glass is of 1921 and of dubious quality but the tracery is fourteenth century. What do you call a large group of saints? A “Martyrdom” perhaps. Here one might wonder if the Reformation ever happened at all! |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The gallery of the Norman south transept. Note the decoration on the tops and bottoms of the columns. The only entertaining example is the dragon on the baluster of the right hand arches, shown in close up (Right) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking into the south transept from the crossing. Right: The west wall of the south transept, now penetrated by the Early English archway from the south aisle. Note the Norman string courses and, above them, a tiny Norman window. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Two “masks” with interlaced tendril on crossing capitals. All of the sculpture is quite unsophisticated, albeit vibrant, perhaps reflecting its early provenance. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Unusually, the feet of the crossing piers are also carved. Again, the style is often distinctly rude, even pagan. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are several areas of decorated string course, some of it carefully hidden behind the organ in the north transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: More decorative string courses. This one is more ambitious. Note also the face peering out of the corner and another carving below that - possibly a now-defaced mask. Right: Remarkably, this - the so-called “Great Coffer” - is believed to be thirteenth century. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An identified knight of the the later fifteenth century. To his right lies the unconnected effigy of a child. Right Above: The child effigy. Right Below: The rather untidy west end. Here we see clear Early English style with a triple lancet - uncommon on a west end - and single lancets to each of the aisles. It is clear that the aisles remain of their original length, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A filled-in doorway of the old Anglo-Saxon church is a precious survivor of the original nave wall. Centre: The font is of alabaster - an expensive and infrequent indulgence. The date is hard to set but I am guessing early fifteenth century. Right: I am not a haunter of churchyards but this monument is very interesting. Apart from its very curious shape take note of the circular band of decoration near the top - then see the picture below. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The alabaster font is enlivened by this course of grotesque faces running around its base. Right: The top of the churchyard monument pictured above. The face is distinctly Norman-looking even down to the little cable moulding at its base. The circular section is a palmette design which also looks ancient, probably early thirteenth century. Have these sculptures been recovered from the church during rebuilding? The circular section would have to be a small capital because I can think of no other place where the profile would be circular, If so, was the face a part of the capital or has it been superimposed? It is hard to believe that these designs were specially commissioned for a monument. A mystery? Or am I reading too much into this? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The church from (left) the south east and (right) from the north. The south transept has been diminished by the aisle and lady chapel which reach as far as the east end of the chancel. None of the original external windows remain making this seem to be a late Gothic church, concealing the Norman core within. The north transept is also sadly diminished and disfigured by buttressing, Note the original north transept roofline, much higher than it is now. Pevsner talks of the north aisle door (not visible here) being round headed and asks if that is evidence of earlier aisles? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The top section of the tower boasts this course of grotesque figures. Right: This corner carving appears to be dressed in a chain mail coif. Interestingly, this form of armour (including the hauberk that protected the body) fell out of use by the fifteenth century so that probably sets the latest date for this carving. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||