|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

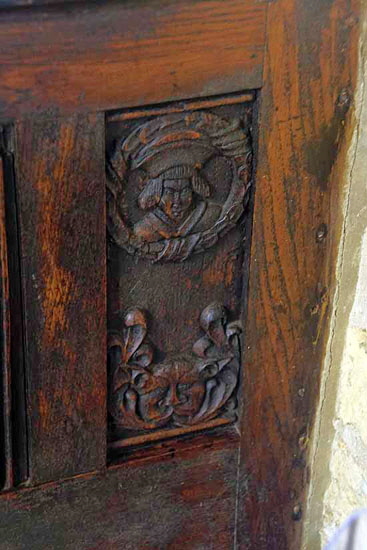

mediaeval cartoon book that will have you simultaneously smiling and scratching your head. They are an idiosyncratic display of the obscure mindset of a mediaeval carpenter. They are simply sensational. What are they doing here? As I said to my friend, if she hadn’t told me where she found them I would have put money on Somerset or Suffolk. For sure there is nothing like them elsewhere in Northamptonshire. When asking “what are they doing here?” we must also ask what are they doing here? You can hum and hah all you like but these carvings are totally secular and there is no question that they are right out of the head of the carpenter – or out of a book. They have no religious meaning. The sheer inventiveness of it all, the artfulness of the compositions suggest that the man was drawing on folk tales and legends. Some have been identified, most have not. |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: The east end. Right: Looking towards the west end. The tower arch is a mean little affair matched by the narrow north door (below) which is now the entrance to the church. The pews for the more common sort cluster around the west end, surrounding the arcade pillars. The Knightley pewis on the south side to the left of this picture. Thus, only the Knightley’s really got close to the “action” in the chancel. Between the other pews and the chancel arch there is a considerable unoccupied space. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: Looking across to the east end of the south aisle. Beyond the monument are the Knightley pews. Right: This splendid alabaster monument is to Sir Richard Knightley and his wife Jane Skenard, There are twelve weepers in all, representing their eight boys and four girls. The girls are visible on this side. Sir Richard was a sheep farmer on an industrial scale. The Church Guide suggests that he kept 2500 sheep in 1539 and “gathered” the fleeces of four thousand others in the area. |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The Knightley monument from the south east. Right: Standing in pairs are the male offspring, offering a splendid study of the costumes of the day. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The west side of the tomb. Centre: This monument to Sir Edmund Knightley (1491-1542) and his wife with their six daughters (what a nightmare!) is in the central aisle and is in splendid condition and would delight the dedicated brass hunter. Edmund was a Commissioner charged with the suppression of the monasteries during the reign of Henry VIII. He had a feud with the Spencers of Althorp (yes, those Spencers!) and then got himself embroiled in another row that saw him imprisoned - see below. Right: Both Edmund and his wife rest their heads on cushions. Edmund’s is an odd composition (Right Upper). To his left a head of a stag is emerging. To the right of his head is a buckled belt, here is more but it is difficult to discern. Several pieces have been used to make the whole. Elizabeth’s is an altogether simpler design. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The spectacular and in no way hubristic monument to the Knightley family between 1566 and 1619 in the north aisle. No more to be said, really. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left and Right: The font is described thus in the Church Guide: “The major part...is early thirteenth century, although the original carving has clearly deteriorated, and has been reworked”. Diana and I exclaimed in unison “Thirteenth Century?”. It is a very odd piece for that time. A perusal of Francis Bond’s celebrated “Fonts and Font Covers” revealed only one example (at Michelmersh in Hants, of a font of that period with the popular head at four corners design. Popular, that is, in pre-Conquest and Norman times. It doesn’t even look thirteenth century, does it? The thirteenth century was a time of retreat from beasties towards a fairly minimalist approach - no doubt influenced by the Cistercians whose star was in the ascendant and who would have despised this font with a passion. So, for what it’s worth (and nobody else seems to want to contradict the Church Guide) I think it’s Norman and I’m not sure you could rule out Pre-Conquest although I would never make so rash a claim. I suspect everyone has just assumed it is contemporary with the earliest parts of the present building. I am going to stick my neck out and say that it far more likely to be a survivor from an earlier church. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

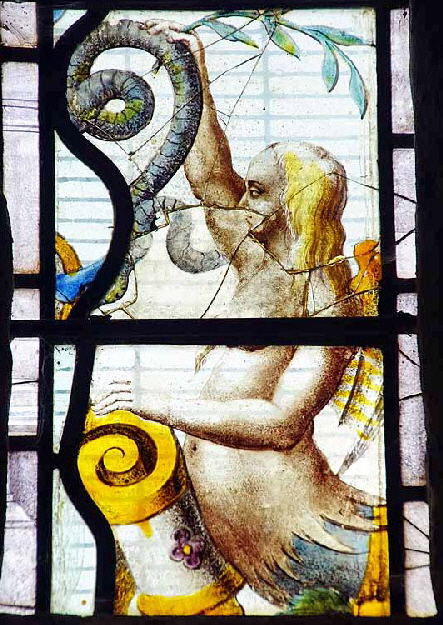

The gorgeous glass in the lancet window of the south west corner of the church. The Church Guide claims a date of thirteenth century. I am no expert about stained glass and this window has clearly become fragmented at some time and the discontinuities are painfully obvious. Looking at the head of this lancet window, however, you can see that there is a crown/diadem design that fits perfectly so it looks as if the glass was originally here. However, the fragments around the outside don’t seem to fit and imply a larger canvas originally. Thirteenth century? I just don’t know. The figure of Eve looks very sophisticated for that time and so does the bird of paradise. but, as I say, I don’t know enough. It really needs an art historian - and to be fair that’s probably who told the authors of the Church Guide it was that old in the first place. My money is on its being later and having been placed here after the fragmentation occurred, We are seeing Eve being tempted by the servant here (right). Her breasts are artfully concealed by the leading. Was Adam ever part of this window? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The glass is a mixture and I only an expert could tell you the date of each of the panels here. In the centre of this panel is one of the arms of the Washington family (yes, George’s forebears) that were brought here from Sulgrave in 1830. The giveaway is the three red stars. The roundels you can see are claimed by the Church Guide to be fifteenth century Flemish imports. The date is surely wrong and most authorities put as being seventeenth century. Centre: The Church Guide suggests this is Christ on his way to Jerusalem. It is very interesting, Christ is be-nimbed at the centre. He is like all the figures clean-shaven and all the figures are distinctly seventeenth century in appearance and wearing long brown robes and “Geneva Bands” around their necks. This neck wear dates from around 1636 and they are very distinctively Protestant at a time when Flanders was predominantly Roman Catholic. Christ is pointing his way forward. In the background similarly-dressed men are tilling the fields. Two more are praying. There are three churches in the picture. So is this, after all, Christ on his way to Jerusalem? I’m really not convinced but if not then what? Right: This one is utterly bizarre. A group of men surround a table where the central character is slicing open some unfortunate animal - who may or not be dead, may or not be cooked - with a knife. Diana suggests it looks most like a meerkat and I can’t disagree with her. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This roundel is an absolute cracker. Death - the skeletal Grim Reaper - is taking his scythe to a bunch of men. He is very curiously drawn. In the background right is a distinctly eastern-looking town. The Reaper’s victims are wearing the same Greco-Roman costumes as in the meerkat roundel. There’s a severed head in there somewhere. The only explanation I have seen is that it represents the death of the firstborn, the last of the the Plagues of Egypt as described in Exodus C 11 V 12:36. I am indebted to Joel Bybee for this explanation that is the only plausible one I have seen. What a very curious subject this is for glass in an English parish church in the post-Reformation period. The story itself is, let’s face it, grim. The random killing of innocent people is not exactly compatible with the idea of a merciful God and it is has uncomfortable parallels with the Massacre of the Innocents ordered by Herod the Great as recounted in Matthew’s gospel. If anybody is offended by that observation then I can only apologise but that’s how I see it. I can’t believe anyone in Fawsley commissioned this work or many of the others for that matter. Were they bought as a job lot and never intended for this - or possibly any other - church? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Heraldry in stained glass, again with the Washington family much in evidence. Right: I’m fed up with writing about glass so let’s turn belatedly to the pews that really are superb (not that the glass isn’t superb too, of course). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

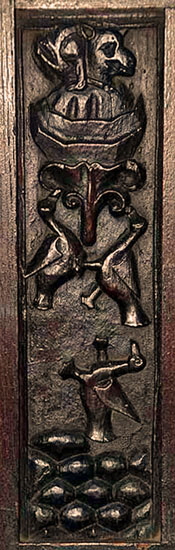

Left: A bear is sitting on a pot. In his hands he offers a large jug to a woman who looks quite chuffed to receive it. What’s in the jug. though? Maybe this is a mediaeval version of the notion of bewaring Greeks bearing gifts? Below them is a jester or fool. He has a long tongue with which he is licking something. The end of his fool’s hat is an animal of some sort and he is eating the plant in front of them both. Second Left: I’ve No idea what this is. See how the man’s ears form into wings. Second Right: What looks like a man is being berated by some sort of grotesque figure. Below them are a snake and a frog. At the bottom is a plant bearing flowers. Far Right: At the top is a fairly normal-looking bloke in a hat. Below him is a chained bear. At the bottom is another man on his back for no apparent reason and blowing a horn. Is he a huntsman? Two other mediaeval explanations for horn-blowing are warning of the approach of strangers and announcing the availability of fresh-baked bread. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This is a grand looking dame in a bonnet. What, though, is the significance of a tree apparently growing from a barrel? Second Left: Well, I reckon this is a dog but those things that look like leaves are in fact coming from his mouth. Canine speech bubbles? Second Right: Well this is a real beauty. A fox is playing a fiddle followed by two other smaller foxes - mummy fox and little fox? They seem to have a number of dishes below their feet but they are probably more to do with the odd creature at the bottom of the image busily helping himself to the contents of a cooking pot! Where is the cook while all this is going on? Far Right: This unfortunate man is having his eye pecked by a bird. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: They don’t get any easier. Two birds seem to be pecking at a plant underneath...what? I can’t make this one out at all! Second Left: A man looks down on a curious pair who seem to be confronting each other, The pointed nose of the man on the right who is wearing a clownish hat seems to be poking the ey of the man on the left. Another man looks down with interest. Second Right: The top bit seems to be from the symbolism of the Passion of Christ within a shield: bleeding, heart, feet and hands. Meanwhile underneath this two grotesque creatures are bound together. Right: Spooky or what? A cadaver is rising from his tomb complete with a cross on his winding sheet. There’s a couple of bones floating around. To the skeleton’s right a man’s face is looking down, seemingly attached to the dead man. The coffin has a cross. On it to the right is what looks like an empty pouch or purse. To the left of the skeleton is another empty pouch apparently turned upside down. This obviously has some jokey allegory attached to it. Is it something to do with money (hence the pouches) and death? |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This one is utterly bonkers. A couple of legless monsters, heads all over the place and a bird. Second Left: More bonker-isms. A beast rides what looks like a pig. He’s holding a spear that seems to have impaled a heart. There’s a jug or flagon and an owl. Second Right: It looks like a page of the Karma Sutra - not that I own a copy personally and any encounters I have had with it were purely in the interests of literary research during my early teens - but the Church Guides suggests “three wrestlers”. There are a couple of problems with this rather inventive explanation. The first is - three wrestlers? Whoever heard of three wrestlers? The second problem is that the guy at the back actually doesn’t seem to be involved, What’s more, his legs seem animal-like and am I the only person to have noticed that he seems to have - um - a protuberance? It’s the two chaps in the foreground that are grappling with each other. And the guy at the bottom of this melee has his face in a place that faces don’t often go especially when you are having your head rammed into the floor. So draw your own conclusions. This carving is within two strokes of the chisel of being the most obscene in the history of the English parish church - and I’ve seen a few! Right: Oh blimey, I don’t know! The world’s tallest monkey using the world’s most oversized and ornate ramrod in a small pot. |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Left: At the bottom are a couple in bed getting quite friendly with each other. Above them is their collection of pots and drinking vessels. Second Left: A bit of piety for a change with a bishop’s mitre and the Eucharist vessel. Second Right: More instruments of the passion: the scourge, torch, pillar and ropes with the cock crowing at Peter’s betrayal. Far Right: More madness. The creature on the right looks like a pig. The one on the left? Answers on a postcard please! Is that the Sun looking down with the very disapproving face? |

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: Another combative scene. A dragon on the left is grappling with what is a more humanoid figure on the right with a tree separating the two. The dragon has forked tongue and a curled up tail. The “man” has hold of something in the dragon’s right hand. Bizarrely the tree is capped by a crown. Bizarre, yes, but I have a theory what this means. Henry VII flew the Welsh dragon on his banner at Bosworth Field in 1485. Richard III on the right is made grotesque by design and the row of protuberances may be indicative of his deformity. A large flower - a rose? - is above each man’s head. The crown, by tradition, was found in a bush. I think this is a scene commemorating Henry’s victory at Bosworth. But feel free to dismiss this as nonsense. If I’m right, though, it dates the pews to probably the late fifteenth century. Centre: A cat maybe? Not a very good one! Second Right: This one’s a bit hard to see but that’s a green man at the bottom. Right: A cat chases a mouse - presumably. What is that above the mouse’s bottom? |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

Left: Squints are always a matter for debate. Were they there to allow a view by the congregation of the Eucharist being raised? Or were they they there to allow a clerk to see the Eucharist to be raised so he could see the right tine to ring a bell? Well this one is directly in line with the Knightley pews so here, at least, we can assume it was the former rather than the latter. Centre: The west end with two Knightley family funerary hatchments. The tower arch is a peculiarly narrow affair. Right: Entry is via a north door and it too is very narrow. Its shape is very clearly English and along with the lancet window in the west end of the south aisle it supports the notion that both aisles were built in the early English period along with the nave and chancel. Note the elaborate gates to avoid unwanted visits by the sheep that graze in the fields outside. |

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Left: Fawsley Hall is at the end of the same access road as the church. Today it is a popular wedding venue. Right: The church has a forthright, four-square appearance, emphasised by the rectangular Tudor period windows. Only the east end has escaped in this shot from the north east! |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south west. Right: The south side. It is a little less austere than the north and broken by this hefty porch, although entry is via the tiny north door nowadays. |

||||||||||

|

Footnote - How Old are the Pews? |

||||||||||

|

This is a question I was asking right from he start. Doubtless other writers were too but they have studiously avoided addressing what is a vexed question. I have already called into question the claimed dates for the font and for some of the glazing in the church. On the question of the pews the Church Guide lamely says “they were restored by James Dawson on 1992”. That raises the dread question of how much were they restored? My guess would be not very much. Certainly I don’t think there is any doubt that these carvings were out of the head of a carpenter at least five hundred years ago. No modern carpenter would know where to begin devising such drollery. Indeed. in my view, not least of the joys of these pews is that they show us how hopeless is our quest to understand what such decorations are supposed to mean. I like that hopelessness. I don’t want to know what the carpenter was thinking - although it’s good fun to speculate. So how old are they? Well let’s start by being exact with our terminology. Strictly speaking a pew is an enclosed seating area such as we see here at Fawsley and often called a box pew. The seating most commonly seen in mediaeval churches are benches, not pews, and the distinction is visually obvious. If I am right in my interpretation of one of the carvings as representing the Battle of Bosworth and the end of the Wars of the Roses then not earlier than 1485. The carver - or in this case more likely his patron - was judiciously making public his allegiance to the Tudor dynasty. The more informed of you will know how unhelpful an insight that is because it is most unlikely that such blocks of pews were installed in any English church as early as 1485 anyway. In style, however, it must be said that the carvings are totally comparable with those found on bench ends in England at that time, especially in the West of England. The carvings here are just as unfathomable and just as cheeky. I might add that they are mostly secular too, although we do see some unmistakable religious imagery in the appearance of the instruments of the passion. There will be those that will try to stretch that fact to accommodate the idea that all of these carvings - and myriads more all over England - must all be construable as Christian teaching if only, if only, our impoverished modern minds could see it. To which I say “baloney”! As I always do. When, as I have done, you try to find a history of church seating you realise once more how little we know. What we do know is of the existence of wood carving workshops in various parts of the country - the West Country again to the fore but also commonly in Norfolk and Suffolk - and we even know the names of some of the carpenters who carved ornate bench ends. From that we know that carving of the type found in Fawsley was around in at least the fifteenth century. Amongst the meagre references I have been able to find for the dating of box pews, the earliest date I have found is “before 1577” in Ludlow. As many commentators say, it was after the Reformation that seating became more important because hapless parishioners now had to be harangued at length by priests. Yet these Fawsley carvings look pretty naughty for so late a date. So after all this, we are no closer to a date for the pews here. One of the keys to all of this is may well be the “linenfold” style that can be seen at the bottom of all the pew panels at Fawsley. This was popular throughout Northern Europe until the sixteenth century. It seems, though, that it started to go out of fashion in the sixteenth century as renaissance styles became popular. When we look at the Bosworth panel - and bear in mind this is my own interpretation - then we should ask ourselves for how long the Knightleys would have felt the need to state their allegiance. Certainly during the reign of Henry VII (d.1509) when all loyalties were suspect. Henry VIII knighted two family members before dying in 1547 so their loyalty was by now thought unimpeachable - at least to the extent that Henry regarded anyone’s loyalty as unimpeachable! Is it likely, though, that the family still felt the need to make this statement during the reign of Edward VI - who died at the age of sixteen in 1553 and who came to the throne all of sixty two years after Bosworth? Moreover the decoration is very mediaeval and it is hard to believe it was carved long after the onset of the Protestantisation of England in Edward’s reign (1547-53). So I am suggesting that the pews here date from between 1485 and 1547 and probably a lot earlier than 1547. That would make Fawsley’s pews amongst the oldest in England as well as the most ornate. Everything we know about the Knightley family tells us that would have been both rich and cosmopolitan through their part in the wool trade and that they liked to demonstrate both those things. The glass in the church is Flemish and it is my bet that this panelling was also adopted from Flemish styles. Indeed linenfold style originated in Flanders. Unless, of course, you know something that I don’t...?

|

||||||||||