|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

of Earl Godwin of Wessex whose son, Harold, was to meet a sticky end at Hastings thirteen years later. Godwin was the richest man in England and probably also commissioned the much grander church at Bosham in Sussex that you can also read about on this site. If you like English churches that connect with our island history then Idsworth should tick boxes for you. The church has just two cells: nave and chancel. The north wall has the only real evidence of the age of the church: a tiny round-headed window and a filled-in north doorway. The position of this doorway is a curiosit. It is sited at the east end of the nave, far further east than a conventional north door and on the “wrong” side of the church for a priest’s door. The Church Guide suggests the possibility that it led to a now-demolished north chapel. It also says it is only twenty-one inches in width. Those two things might support the contention that the building was tenth century. Entry today is via a simple west door, the age of which is hard to ascertain. My best guess would be thirteenth century. It is protected by a pretty eighteenth century porch. The chancel arch is both large and pointed and dates from a complete rebuilding of the chancel in the twelfth century. Perhaps the west door was inserted at that time? We can only speculate where the original entrance was. Favourite would, of course, have to be in the south wall of the nave but that was replaced in the sixteenth century so no evidence remains. The treasure here, though, is the wall paintings. Pevsner calls them “The most important series in a Hampshire church apart from Winchester” and dates them to 1330. I will describe them in detail below. It is worth mentioning now though that one of the panels was long believed to represent St Hubert. This is presumably why the church was re-dedicated to him, having previously been dedicated to St Peter. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: Exaggerated only a little by a wide-angle lens, this is the church as seen from the road. It hardly needs saying that it is easily missed. But what a setting! Right: The west porch and doorway. |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Left: Another view of the approach to the church. Centre: The west door in all its simplicity. Right: Looking west from underneath the chancel arch. Note the rather outsized and definitely oddly-situated royal arms of George III. Its border proclaims two churchwardens of 1795 and 1824. It seems their ambition was out of proportion with the church! I like 1795, though. 1789 was the date of the French Revolution so anything around that time gives a nice sense of historical perspective. The England of “Thomas Padwich Churchwarden” would have been looking nervously across the Channel at our neighbours who had cut off the the head of its monarch and dispatched tumbrils full of aristocrats to Madame la Guillotine. Would the contagion spread? What did Thomas Padwich make of it all? |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The view towards the east end is dominated by this (dare I say incongruous?) - Millennium fresco depicting, amongst other things, Christ in Majesty. Right: Looking again towards the west end. The gallery is a surprising survival but houses the organ very handily. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left: This picture captures both the early survivors of this church. On the left is the deeply splayed Saxon or Norman window. Just next to the chancel arch is the ancient and rather enigmatic north doorway. Beyond the chancel arch you can see the mediaeval frescos. Right: This picture of the north wall shows the early features from the outside. |

|

|

|

|

|

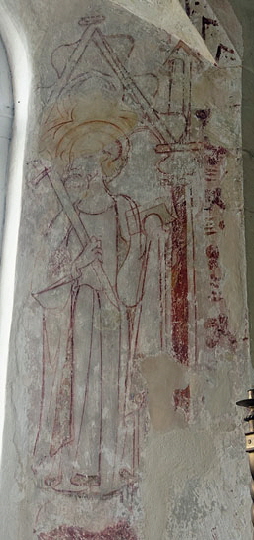

Left: The chancel. The east window is about as plain as plain can get. Yet its simplicity is almost beguiling in this humble context. Fortunately the window setting still has its mediaeval paintings. The ceiling was replastered in 2013 and given attractive polygonal settings for pictorial designs. Second Left: In the north side of the window is St Peter holding a no-nonsense key to the gates of heaven. He is in bishop’s robes, emphasising his status as Bishop of Rome, a status beloved of the Roman Catholic Church since his Papal successors are thereby legitimised as God’s representatives on Earth! Second Right: St Paul holds a book in one hand and a staff over his shoulder. Right: The soffit of the arch has two angels. |

|

|

||

|

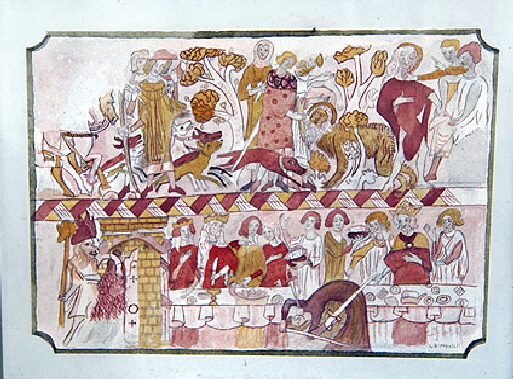

Left: The church provides this convenient illustration of the north wall paintings. As you can see, there are two panels divided by a horizontal pattern. Both are extremely interesting and very graphic. I am going to quote the Church Guide: “It is generally accepted that the lower panel depicts the presentation of the head of St John the Baptist, in a salver, to Salome (the contorted figure in the foreground) at King Herod’s feast (clearly visible in the centre), and that the separate scene at the left-hand end represents St John being thrown into prison. The hunting scene in the upper picture is less easily interpreted and an earlier view that it represents St Hubert converting or curing a lycanthrope (a man who through a form of insanity believed himself to be a wolf has been discounted in a number of modern treatises...” It then quotes recent academics in their contention that “the right hand end of the upper picture depicts the arrest of St John and...the remainder portrays the discovery of a “hairy anchorite”, a hermit who, according to legend, in penance for sins of inchastity and murder undertook to walk on all fours until he knew he was forgiven...” Lycanthropes? Hairy hermits? Where did this stuff come from? Right: The lower panel. It has to be said by someone - so it’s going to have to be me - that the legend of Salome is the most awful bunkum. Salome was the daughter by a previous marriage of Herodias who was married to King Herod. Salome dances at a feast for Herod who is so enchanted, according to Mark, that he offers whatever she wants “up to half my kingdom”. Generous chap, that Herod. Anyway, offered such largesse, Salome could think of nothing better than demanding the head of St John the Baptist because her mother Herodias wanted it. Plausible, eh? Matthew repeated this twaddle, albeit more briefly. They don’t mention why Salome could think of nothing more alluring than the death of a hermit. In fact the Bible doesn’t even mention her by name so there could be some mistaken identity here. Salome existed all right. The Jewish historian Josephus mentioned her in his “Jewish Antiquities”. He recorded that she married first her uncle and then her cousin so she was presumably identified as a suitable object of disapproval by the early Christians. All those gullible renaissance painters and playwrights (including my own favourite Cravaggio) queued up to paint her I reckon they relished the opportunity to paint “sexy” for a change. Funnily enough, Joesphus doesn’t mention her part in St John’s death. In the wall painting Salome is the lissome lass in brown bending down in front of the table with a sword in her hand. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: Salome is in the foreground. Herod is second right. Right: To the right of the picture is Herodias - the scheming cow! To the left the Baptist is being thrown into prison, although I confess I can’t quite make this out myself. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: On the right of the picture John is being arrested. To his left is the “hairy hermit”. The whole thing is a bit odd. The party “discovering” the hermit is undoubtedly a hunting party: there are four dogs, a man with a horn and fragments of a horse with stirrups. One wonders what would follow the “discovery”? The hunting party is rather suggestive of searching and capturing. It’s most peculiar stuff and one wonders whether the parish priest would understand all this, never mind the parishioners! Right: The hounds and a huntsman with a horn. |

|

|||

|

|||

|

Left: The hairy hermit - supposedly. I haven’t read the background to this story and I’m sure the writers knew what they were talking about. It’s curious, don’t you think though, that the “hairy hermit” has fur that looks like that of a lion? He is on all fours, we can agree on that, but his hair and beard are not so very unkempt and the shape is more in keeping with a man/lion rather than a man on all fours. In his hand he seems to be holding some kind of document. Right: This roundel is set into the east window is a copy of a Durer engraving depicting the conversion of St Hubert. It was the gift of the architect who carried out the 1913 restoration. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

Left: I don’t often advocate the use of limewash or rendering but perhaps I can be sacrilegious and suggest that Idsworth’s north side might be the better for it? Note the tiny bell wooden bell-turret. How old it is is anybody’s guess but there is no reason to suppose it is not ancient. One of the oddities of the church (have you spotted it?) is that there are no graveyard monuments. That’s pretty unusual but remember the church has never served a village, rather it has been manorial. There is, however, evidence of graves in the vicinity. The Church Guide talks of rumours of nearby plague pits but that is hardly the same thing. Right: The view from the church back to the road. |