|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The busy A1 ploughs its way between Grantham and Newark for a distance of about 16 miles. Both towns boast large and prestigious churches of which they are justly proud. Much as I admire both of these churches and other large towns like them, however, my heart belongs to the unassuming little country churches in the backways and lanes of rural England. From Grantham you can follow small unclassified roads due north before crossing the A17 and arriving at the wondrous church of St Helen’s Brant Broughton with its Gothic fancies, ancient and modern, and its riotous array of mediaeval carvings. Just one and a half miles south of Brant you can visit the tiny humble little “farmyard” church of Stragglethorpe that has never been appropriated by the rich and powerful but which has remained at the heart of its tiny community for a thousand years.

From Stragglethorpe you can follow the road to little village of Brandon. Here you can find another tiny church that is as ancient as Stragglethorpe’s but which has been continually altered over the centuries to leave a little mongrel of a church. It was not even designated as a parish church at all but as a “Chapel of Ease” to save the local landowner from having to trek (on horseback, of course) to the parish church at Hough-on-the-Hill, a massively inconvenient two miles away! Yet it still stands, as much the centre of its community as St Helen’s Brant Broughton is of its own, an attractive little church in a pretty rural setting; as English as scones with jam and cream. Two miles from the A1 it could as well be two hundred.

Then you have Hough-on-the-Hill itself and here we are in the realm of the truly ancient with the oldest parts of its substantial church probably dating between AD950-1000 and having one of only three or four Anglo-Saxon stair turrets left in England and a Norman font.

The back road joins the A1 a couple of miles north of Grantham and we are back into the hustle and bustle of “The Real World”. There are other churches on the back route, of course, but these four churches: Brant Broughton, Stragglethorpe, Hough-on-the-Hill and Brandon present a super little microcosm of the charm and diversity of the English parish church. Next time you are in Grantham and Newark and you have some time to spare, do yourself a favour: take the back road, chill out and enjoy.

There are separate pages on this site for Brant Broughton and Stragglethorpe. Read on for Hough-on-the-Hill and Brandon.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first thing we have to get straight here is that we pronounce the name, as “Hoff” not, as I thought for years “How”. Nor is it pronounced as “Huff”, “Ho” nor as “Hoo”. How do you foreigners cope with our language?

There was a church at Hough recorded in Domesday book, serving a community of forty five households and four mills. Quite why such a small village justified a stone church at a time when so many were of wood and thatch we don’t know; nor do we know whether there was a such church before the stone one was built. There is a lot of archaeological work going on in the village and its surroundings and it is very clear that the site has been inhabited for a very long time.

The seasoned church crawler will immediately spot the Anglo-Saxon bell stair to the west of the tower that is this church’s claim to fame. Taylor & Taylor’s “Anglo-Saxon Architecture” puts it in the period AD950-1000 although the Church Guide suggests eleventh century. Of course, the tower it serves is also Anglo-Saxon, albeit with a fifteenth century belfry, but it is not clear whether or not the bell stair was added later or whether they are both contemporary. It is noticeable that the tower string courses are not continued into the stair, but this is not a definitive argument for separate dates.

|

|

|

|

|

The Anglo-Saxon bell stair is almost unique. The most celebrated other example is at Brigstock in Nothamptonshire. The nave walls are also Anglo-Saxon although they have, of course, been penetrated by later aisle arcades. Again, the experienced church visitor will note the inordinate height - ten metres, no less - which is so characteristic of the period and which would originally have been roofed in thatch. The nave is older than the tower or its stair which were built against its west wall. We know this because the original quoins of the west wall are still visible. A clerestory was added in the fifteenth century. You can see the original roofline very clearly on the east wall of the nave. Inside the church you can see the expected Anglo-Saxon tower arch. It is an undramatic example compared with some. High above it is the, again expected, blocked doorway that may have given onto a western gallery made of timber. This is triangular-headed as would have been expected, although it is not obvious from within the nave.

It is interesting to speculate what the original church looked like. Would it have been a single-celled church? That seems unlikely. There may have been a small porch at the west end over which the tower now sits and there may have been a shallow, perhaps apsidal, chancel over which the present structure sits. I suppose we will never know. There is no sign of Norman work within the church which is very unusual for a church of Anglo-Saxon origin although, again, we have no idea what preceded the existing chancel. Often we can rely on evidence of an earlier chancel arch but there is nothing visible here although the Church Guide notes that the stone of the upper parts is newer. The chancel arch we see today is Early English. The east window is fifteenth century. The north side has a small arcade leading into a north chapel that was rebuilt in the nineteenth century.

Both aisles are thirteenth century with Early English arches. Both were raised in the fifteenth century. The north wall was rebuilt in the eighteenth century (a time when churches were often left to rack and ruin, it must be said) in brutal fashion with horribly incongruous rectangular windows of the most industrial ordinariness and, heaven help us, a north east wall in red brick. And to think I criticise the Victorians....

The font is a solid and unpretentious rectangular piece with an odd series of sides with round headed arcading, blind arcading and Gothic arcading almost as if the mason were demonstrating the evolution of the arch.. I think we can fairly safely assume that it is from the Transitional period or possibly contemporary with the Early English aisles.

I don’t think the rebuilders and restorers have been kind to this church. There is a depressing hotchpotch of windows with little apparent effort to blend the new with the old; the south aisle alone shows four different designs. That though is all mitigated by the survival of the Anglo-Saxon tower and staircase. There is a great deal to be read about this and if you want to know more I would recommend Taylor & Taylor’s work if you can get to see a copy. No, you can’t read mine.

|

|

|

|

Aspects of the tower and stair turret. The extent of the original tower is very clear to see. The lowest tier is unusually shallow. Note the string courses which are not continued into the turret. The tiled roof on the turret is not, of course, original. The tiny windows for the landings are very obvious. Note the unusual arrangement of windows in the tower either side of the turret. The aisles are very shallow, never having been extended outwards as was commonplace in the later mediaeval era.

|

|

|

|

Left: The original Anglo-Saxon tower arch is neat and with smaller and neater stonework than at many Anglo-Saxon churches. There is general agreement that the tower was added to this west wall but an odd silence about what, if anything, preceded it. A west porch - or Galilee - and entrance is a plausible theory. In which case it is not clear whether this tower doorway was built when the nave was built or whether it was added with the tower. Centre and Right: These two windows in the stair turret are superb examples of Anglo-Saxon design.

|

|

|

|

The font is a remarkable affair. Top Left: On this side we see distinctly Romanesque-looking arches. The effect is heightened by the zig zag moulding at the the rim. It’s a more refined composition than we would expect on a Norman font, however, and the other sides quickly dispel any lingering doubts. Top Right: This side reproduces the blind arcading seen on many a Transitional or early Gothic church inside or out. The carver hasn’t quite managed the considerable challenge of getting the geometry right on such a confined canvas. Various images including a man’s face peer out from the intersections of the arches in rather Norman fashion. Bottom Left: And now we have a run of unequivocally Gothic arches! the fourth side, if you are wondering, is completely plain! The four corners of this font are rather disappointing since we are used to their being adorned with faces or monsters. Again, this reassures us that it is not a Norman font that we are looking at. I think we can safely assume it was was early thirteenth century. Bottom Right: The chancel.

|

|

|

|

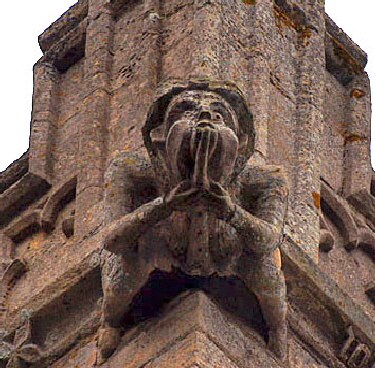

Left: There is a rather mean little frieze under the tower parapet that is in stark contrast to the wonders to be seen up t’road at Brant Broughton. I tend to scoff at those who try earnestly to find hidden meanings in the flights and fancies of the mediaeval masons but at Hough I do feel that there may be something to be read into some of the carvings. It is the very abundance of carvings at Brant Broughton - and indeed at most of the churches I discuss in my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” - that convinces me that the notion of their having “explanations” is fanciful. Here there are very few and although most can be dismissed as run-of-the-mill animals and fleurons we can see in this picture an owl in a remarkably un-owl-like posture, a six pointed star, a Maltese cross and a monogram - which can be seen better in the picture below. The monogram must have been of some patron of the church, but I can’t discover which, and I do think that the star and the Maltese cross must also have been of some significance in the eyes of the mason. Right: masons loved to carve musicians and this is a particularly nice example of a man playing a shawm. If you look to his right there seems to be another monogram.

|

|

|

|

Top Left: Another corner carving on the tower. His hat is held in place by some kind of some cloth, seemingly. Something projects from his mouth on the left hand side. What can it be? The mouthpiece of a musical instrument? His own finger? Top Centre and Right: A couple of beasts that would have won no awards. Bottom: The “WT” monogram. Who could this have belonged to? Could the mason have cheekily left his own mark?

|

|

|

|

Brandon: St John the Baptist Simon Jenkins: Excluded

|

|

|

|

|

|

I don’t know how many people visit the little chapel at Brandon - as opposed to attending services - but I suspect it is vanishingly few. A friend of mine alerted me to its existence and borrowed the key. Then I went to her house for freshly-picked raspberries from her garden and ice-cream. Brandon is that sort of place: a deeply rural and little-known community that has been shunted into a siding off the main line that is the A1. That, of course, is what attracts today’s residents: a tranquil place to retreat to after the hurly-burly of the modern working day.

I haven’t been able to find out much about about Brandon’s history. There is plenty of archaeological evidence that the area around Brandon and Hough has been settled for a very long time. Hough, as we have seen, was a settlement at least in the Anglo-Saxon era. “Brandune” as it then was appeared in the Domesday survey of 1086 but there is no mention of a church. Various names are mentioned. The most important is Gilbert de Ghent (1040-95), a kinsman of the Conqueror. In the feudal system imposed by William all land was ultimately his and he doled out chunks of land to those he favoured and for services to be rendered who in turn doled it out to those they favoured and for services to be rendered, all the way down to the social hierarchy until you reached the landless serfs and slaves.

|

|

|

|

|

Gilbert was designated “Tenant in Chief” for no fewer than 176 manors, mainly in Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire. He lived in nearby Folkingham and became Earl of Lincoln. Both in Brandon and in Folkingham the name “Derinc” appears and it seems that he was the man who was Lord of the Manor at these two places deriving his land under the patronage of Gilbert. Do not be misled by the modern connotations of “tenant” and “lord”. A Tenant in Chief to the King was a cheese of very large proportions indeed! Both Folkingham and Brandon, by the way, were held by “Ulf” - a common Anglo-Saxon name - in (and presumably until!) 1066.

Although there was no church at Brandon in 1086, we know that today’s church originated in the Norman era because it retains a Norman tympanum. Today it is officially called a “Chapel of Ease”, having no parish of its own, being subsidiary to Hough and having less onerous obligations. That would not, however, have been an expression that the Normans would have recognised. In fact most Norman churches were built by the local lords for their own benefit and prestige and this was undoubtedly true of Brandon. One might say that most Norman churches were “Chapels of Ease”! Brandon was most certainly not built to avoid the occupants of fourteen feudal households having to walk a miles and a half to church, of that we can be quite certain!

The church we see today was remodelled by Charles Kirk of Sleaford in 1876 “with plenty of old materials” as Pevsner puts it, having seemingly become unfit for use. Sadly, nobody seems to have a clue what this church looked liked before its restoration or how it developed over the centuries. In essence it is a single-celled chapel with no sign that there was ever any separation into nave and chancel. There is a windowless “north aisle” that is so shallow as to be functionally useless. It stretches along most of the north wall and has what is something of an apology for a north chapel that contains a couple of empty niches. The two-bay “arcade” is of wooden beams supported by an Early English round pier and with two semi-octagonal responds at the east and west ends. There is a similar arrangement leading from the chancel into the north chapel but the responds look later suggesting the aisle was extended eastwards at some point. Each of the piers has been augmented by large chunks of masonry to lift them to the level of the wooden lintels. It’s an ugly arrangement, presumably bodged together by Mr Kirk in 1876 but the pier and the responds seem likely to have been in-situ and it is hard to believe that Kirk added a nugatory north aisle - complete with original gothic niches - from scratch. Looking at the Early English pier it seems plain that if it originally supported a masonry arch then the north aisle roof would have been rather higher than it is today. That suggests it might also have been wider and therefore more usable. It also suggests that the nave roof was higher than it is now.

The south wall has curious wedge shaped cross-section that is very obvious from the inside. The masonry is thicker at the bottom producing the illusion that the wall is leaning outwards and that is only dispelled when you realise that the windows are vertical. The wall has two rectangular windows. One appears to be sixteenth century and the other probably dating from the Victorian restoration. A Gothic style arch at the east end of the wall suggests that the chancel was extended a few feet at some point. The window immediately to the east of the porch is neo-Norman and it seems likely that Kirk simply remodelled an original Norman or Transitional window opening.

What are we to make of all this? My guess is that the original Norman church was single celled and extended east only as far as the buttress on the south wall. The north aisle was added with a conventional two bay arched aisle and was rather higher and wider than it is today. It would have had one or more windows. Finally, I think the building was extended east, necessitating the buttresses on south wall and east end. The aisle was also extended eastwards to house the north chapel whose perpendicular style niche suggests mid-late fifteenth century. Then it all fell to pieces through neglect from 1650 onwards as so often was the case until Mr Kirk rebuilt it reusing whatever was still serviceable. I am, I emphasise, just guessing.

The tympanum and door lintel has mainly chip-carved St Andrews cross decoration but towards the top and centre this gives way to a chevron-like decoration. One wouldn’t want to over-sell it, but it is rather more sophisticated than it appears at first sight. There is an outer course of decoration that Pevsner describes as “really an Anglo-Saxon motif”. The existence of a pre-Conquest church, however, is almost precluded by Domesday. Only “almost” because there are, believe it or not, fifteen known examples of Lincolnshire churches having been unrecorded by the Domesday information gatherers.

We will all have to try to forgive the idiot who casually decided to chop away some of the pattern on the lintel to accommodate a b****y electric light that seems to have come from B&Q. If the said idiot is reading this, don’t worry yourself too much. It had only survived a thousand years, after all. I’m sure the light was worth it.

I’m not going to pretend this is a church you will want to visit for its architecture. Apart from the tympanum it is all pretty ordinary. if you are travelling “The Back Road”, though, don’t pass it by. Our churches are a rich tapestry telling us the story of our past. Brandon has its place in that story.

|

|

|

|

Left: The south side with its curious collection of windows. The one to the right of the porch might be an original Norman window space. Kirk clearly inserted the one next to it somewhat cack-handedly. Then we have a Tudor-style rectangular window. The buttress and gothic arched window probably marks a modest extension eastwards. Right: The complementary south door lintel and tympanum. Note the way the pattern changes towards a kind of Norman chevron design towards the top. It’s all a very simple design to our modern eyes but geometrically it is not unsophisticated and if you can adjust the perspective of you eyes you can see that quite nice rhomboidal patterns are produced where four squares intersect. Don’t underestimate the skill required to get all this right. You will see many pages on this website where Norman masons failed spectacularly to get things right! Note the outer course of decoration that Pevsner suggests may be Anglo-Saxon.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking towards the east end. Note the arch to the north chapel left of the altar. Right: The view west. The odd profile of the south wall is very obvious on the left. It looks as if the whole wall is leaning but on the outside it is more or less perpendicular. You can see clearly how the north aisle is supported by an odd combination of built up masonry piers beneath timber lintels that are part of the roof.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Mr Kirk was never going to win any awards for his building here and his method supporting the roof, whilst presumably effective, might best be described as “brutal”. I had expected to find that Kirk was just a jobbing builder who chanced his arm at church restoration but with his partner Thomas Parry he was in fact regarded as quite an eminent architect and builder. They were responsible for many fine public buildings in Lincolnshire and the building of the churches at Deeping St Nicholas and Sausthorpe, both of which are fine pieces of work. I suppose we must put this piece of make-do-and-mend at Brandon down to budgetary constraints! Centre: The perpendicular style niche in the north chapel. Note the two strangely-positioned carved heads. Just to the right you can see the left hand side of the opening through to the chancel. It gives you some idea of how startlingly narrow the north aisle and chapel are. Right: The south door.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above Left: The west end. The window seems to have been repaired during the rebuilding. Note the way the masonry alternates between courses of dressed and rough ironstone, giving a visually pleasant “banding” effect. This is also used on the north aisle so it seems likely that we are seeing restoration work. Above Right: The church from the south east. Below Left: To the right of the south door you can just about make out this mass dial. Like so many mass dials throughout the country it was rendered useless when the porch was added. Below Right: Pevsner says Brandon Hall is dated 1637, although I have also seen the sixteenth century suggested as a likely age. Like parts of the church it has courses of dressed stone and ironstone making this a particularly attractive building, the residents of which, presumably, most benefited from the retention of the church as a Chapel of Ease.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We can say little about the tub font other than it is undoubtedly “ancient”! It seems a reasonable to assume it dates from the Norman foundation.

|

|

|

|

Footnote - Brandon’s Domesday

|

|

|

|

Let’s start off by reminding ourselves that the Domesday survey was not like a modern census. The Bastard of Normandy (as he was known to those who particularly liked him) wasn’t wondering how many subjects he had and nor was he planning for the building of roads and schools! Like Kings and Governments since time immemorial he wanted to make sure he got his tax revenue. It might not have been as sophisticated as a modern census but it was a remarkable achievement and, having worked for the last census in this country, I have more than a suspicion that William’s was a darned sight more efficient and less wasteful of resources.

Domesday was written in mediaeval Latin, not all of which has straightforward translations, and it made much use of abbreviations. This doesn’t make translation easy, even for scholars. Brandon’s entry is believed to be translatable as follows:

“In Hag and Brandune there are 3 carucates and 3 bovates of land (assessed) to the geld. There is land for 5 teams. 13 sokemen have 6 teams. There are 6 acres of meadow. All this Derinc holds of Gilbert and he has half a team there in demesne. It is worth 40 shillings.”

“Hag” is Hough-on-the-Hill. “Derinc holds of Gilbert” surely implies that Derinc is the tenant as discussed above. What, though, are carucates and bovates? A carucate is defined as “the tract (of land) which could be cultivated by an eight ox plough team”. A bovate is about an eighth of a carucate and in Lincolnshire it would have been the equivalent of about 20 acres of arable land. The basis of land measurement was by no means the same all over England and the word “hide” which denotes the land necessary to support a single family was much more common.

In Kent where they did most things differently they used a “sulung of four yokes”. This was the amount of land of land that could be ploughed in a season by a team of oxen - very similar to the carucate. Why was Kent “different”? It was settled (or, depending on your point of view, conquered) by the Jutes who actually arrived before the Angles. Saxons and Friesians and they had their own ways of doing things. Even today administration in Kent has its idiosyncrasies. If you are a railway buff think of it as the old Great Western Railway and its successors. No matter how hard people tried to make it conform to national standards it always managed to do some things its own way!

Just to digress - and that’s what I use my footnotes for - how fascinating to think of the important of oxen to both England’s agriculture and even in mediaeval times to the tax system.

A “sokeman” was a freeman who was not bound to the land by serfdom. The word seems to have originated in the “Danelaw” - the part of the country over which the Danes would have held power in the tenth century.

What then is “geld”? As you might have guessed, in this context it’s tax. The word “geld” or variations around it has meant “money” or “tax” all over Europe. It means “money” in Germany and the Netherlands even today. Its best-known use in England has been in the the word “danegeld”. This was not, as many suppose, money paid to the Danes and their allies to stop then from further incursions but the tax levied on the populace in order to make that payment. Oddly, it was the Normans with whom even the Vikings didn’t feel like messing who actually coined the expression. “Heregeld” was another pre-Norman word denoting a tax to pay for the army.

How much was the tax? It varied from ruler to ruler, time to time. It was not a Pay As You Earn system and there was no parliament to hold back the King’s avarice or ambition. The danger, of course, was that over-taxation might lead to revolt - not least by the aristocracy - or to famine which would in turn damage future the future tax “take”. Two shillings per carucate or per hide has been suggested as the probable median in Norman times. The tax was payable not by the peasant or serf but by landowners. Men like Gilbert de Ghent, in fact.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|