|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Additions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

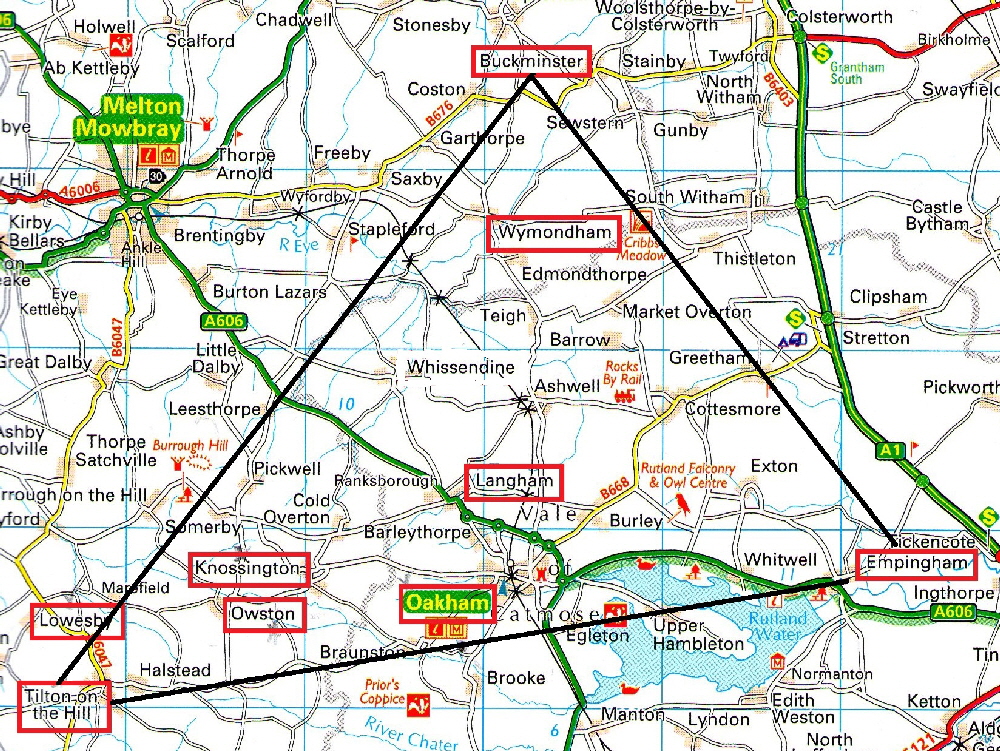

That cornice frieze carving was a local peculiarity in a small enclave of the East Midlands is interesting enough, and is easily proved just by their comparative abundance. The map alone should be sufficient to convince all but the hardened nay-sayer. The true value of this study, however, is in its identification of individual styles of carving that give us some insight into the mobility of the masons and the apparent existence of an organised group or company to which they may have belonged. In the next section we will be looking at the ubiquity of certain “trademark” carvings and later at individual stonemason carvers. The names of very few mediaeval parish church stonemasons are known to us. It was perhaps less a case of undue modesty, more the case that there was no compelling reason for their names to be recorded. The few we do know are preserved because of the few score precious survivals of mediaeval building contracts. Surnames were not the familial identities of which we are so proud today: a mason’s name was most likely to comprise his baptismal name plus the village or town from whence he came: a practice I will emulate later. But first I want to look not at friezes but at gargoyles. Let us remind ourselves that a gargoyle is not an all- purpose word for a grotesque carving: a gargoyle is a usually monstrous figure through whose gaping mouths water is channelled away from a roof to the ground either directly or via a drainpipes. Like corbels and unlike friezes, they are functional. Gargoyles are, of course much larger carvings than those found on friezes. Although we all love to see their ferocious or amusing faces they are artistically one dimensional. Once you have seen a few dozen of them they all tend to blur into one! I have yet to see someone definitively identify gargoyles at several churches that are palpably carved by the same mason. At this group of churches, however, we are going to see just that. We are going to see an unique and iconic design and we are going to see the work of a single gargoyle carver at several churches. Thus we are going to very firmly establish the case for a group of mason-sculptors working at several churches within a limited geographical area. I have already pointed to the importance within this narrative of Oakham Church in Rutland. A frieze carver shared with Ryhall Church was the first clue to the existence at least one mason who could be seen to have worked at more than one church and without having to rely on dubious clues such as shared masons marks. We saw also the presence of no fewer than three exhibitionist “mooner” carvings and we are going to see a great deal more of them at other churches. Another curiosity is a very distinctive gargoyle. The main figure has a startled look and wavy fur. Across his back is a person taking a piggy back ride. The person stares fixedly ahead, her hands clutching the jowls of the beast below. Bizarrely, another figure can be seen spanning the space between the creature’s back legs just above the modern drain pipe that has replaced the gargoyle’s mouth as the water conduit. It is located on the west side of the south chapel. I have dubbed it the “Hitchhiker Gargoyle”. On the east side is another gargoyle, clearly by the same sculptor. His distinguishing feature is is a pair of dragon-like wings folded against his body. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gargoyles, South Chapel, All Saints Church. Oakham, Rutland. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

You can see that both gargoyles have been integrated into a plain cornice and they are surely contemporaneous. Another point to note is that these gargoyles are not located on the top of a tower where you would usually look for a gargoyle: they are at first floor level. The hitchhiker gargoyle can be found at no fewer than five other churches in the area. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hitchhiker gargoyles at (clockwise from top left) : Owston (damaged), Empingham (damaged), Wymondham, Lowesby, Tilton-on-the-Hill. Empingham is in Rutland, all of the others in Leicestershire. Note that all on the body of the church, not on the tower, and all are built into the cornice. Note the clearly visible black lead eye on the Owston gargoyle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There is no room for doubt. This design is too distinctive and the area too localised for coincidence or imitation. The basic design is much the same but Tilton’s Hitchhiker is a little different in that the beast is grasping the lower figure rather than having her between his legs. Look too at the human figures. All have square shaped headdresses. We will see that this will also be one of the defining characteristics of the friezes in this area. Two of the churches - Owston and Empingham - have plain cornices and no decoration. Owston’s gargoyle has an eye socket with a lead insert exactly as we have already seen on the frieze carvings at Ryhall and Oakham. Like the square-shaped headdress this will be an important characteristic in the narrative. It seems likely that each of these gargoyles originally had a pair of such eyes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What does it mean? It doesn’t look like an abduction scene. The women are holding onto the beasts, not vice-versa. The woman astride the monster has a confident look. She is the pilot, you might feel, not a captive. Are they running away from something? It looks rather like it but we don’t where from or where to. We can’t know anything about its “meaning” but the sculptor surely did. We are left to look and speculate. Millions of words have been spent (wasted?) on deciding who exactly was the Mona Lisa and what exactly her enigmatic smile meant. But we don’t know the answer. With these gargoyles as with the Mona Lisa, art leaves us to make up our own minds. We have seen that there was at Oakham a gargoyle with folded (somewhat inadequate-looking!) dragons wings. Here are three more. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dragon-wing Gargoyles at (from left to right): Knossington, Wymondham and Tilton-on-the-Hill (all Leicestershire) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Repositioned and badly damaged Dragon-Wing Gargoyle at Langham, Rutland. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The dragon-wing gargoyles at Knossington and Wymondham have the same between-the-legs figures as the Hitchhiker gargoyles, both with the square headdress. On the Wymondham example we see another case of a surviving lead eye such as we saw on the Owston hitchhiker. Finally, we need to look at one other recurring design. This has the beast holding open toothed jaws located on his stomach. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Jaw-gaping Gargoyles at (Clockwise from top left): Wymondham, Knossington, Buckminster (Lincolnshire) and Tilton-on-the-Hill. Note that two black eyes survive on the Wymondham gargoyle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are then, three unmistakable designs some of the churches sporting more than one. Of the three, the hitchhiker is the most distinguished. Black lead eyes have survived on at least one example of all three designs. Both the hitchhiker and the dragons-wing designs make use of between-the-legs heads and all of the human components have square shaped headdresses, We can do no other than conclude that the carver of these gargoyles - the Gargoyle Master - worked at nine churches at least in this area, even of which also have cornice friezes. These gargoyles are also contained within a very limited area. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In fact, it is likely that this Gargoyle Carver also carved at Whissendine in Rutland and also possibly at Market Overton (Rutland) and Irnham (Lincolnshire), all within or very close to this area, but for now we will stick with the certainty of the nine churches. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Churches did not suddenly decide that they would have gargoyles on their roofs. Gargoyles were a consequence of changes to roofs and thus to the mechanisms by which rainwater and snow was transferred from roof to ground. The Gargoyle Master may have been part of the team of masons that made those changes; or he may have followed that team around knowing that work would come his way. The first – that he was part of the team – is far more likely because if carving gargoyles was all that he could or would do then he would probably have insufficient work to keep body and soul together from month to month. Allowing for the fact that some churches might subsequently have removed their gargoyles, even nine or a dozen churches would total less than one hundred pieces in all. That’s not a career. So we can be reasonably sure that he was engaged in the work of carving the cornice friezes and probably also in the general building work. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Before we leave this topic, we need also emphasise the significance of those square shaped headdresses that we seen on the “hitchhiker” gargoyles. These sartorial oddities date the gargoyles to somewhere between about 1370-1410 when they were in fashion. You can read more about that now by following that this link: Square Headdresses.. Those black eyes are also significant and you can read more about that by following his link. Black Eyes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recommended Next Section: Bums and Fleas |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Gargoyle Master (you are here! Church Building in the Post-Plague Era |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||