|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recent Addition Little Kimble (Buckinghamshire) Wellingborough, St Mary (Northants) Great Kimble (Buckinghamshire) Stamford Church Trail (Various)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

their narrowness and zig zag mouldings in their soffits look quite Moorish. We know that there was a church here earlier in the Norman period, and even possibly in the Anglo-Saxon era. The church of 1190 probably had an aisle-less cruciform plan. In the doorway from the south aisle to the south transept we can see the re-use of some Norman zig zag moulding that was probably from the original crossing - and a heroic piece of bodging it is too! We can see the roof line of the original nave on the west side of the tower on the inside of the church. The transepts and tower were, however, not completed due to lack of funds. In 1232 the Bishop of Lincoln, Hugh de Wells, offered 20 days freedom from penance to encourage people to work on what he called the “ruinous” church - an early documented example of what was euphemistically known as the “Sale of Indulgences” (today we might say spiritual bribery) - that would partly motivate Martin Luther to spark the Reformation 300 years later. This rebuilding was probably finished by about 1240 and the church now also had north and south aisles. The transepts were remodelled in the fourteenth century. The clerestory was added in the fifteenth century when the south aisle also acquired new windows. That was about it until the dreaded George Gilbert Scott arrived to remodel the west of the church in 1861. He gave the church its west window and some rebuilding of the north aisle took place. In saying all this, I concede this work was not one of Gilbert Scott’s many deplorable pieces of neo-Gothic vandalism. He was followed in 1863 by T.G.Jackson who got stuck into the chancel, replacing amongst other things the east window with an Early Gothic style three light lancet. In truth this is probably more in keeping with the church’s origins than the seventeenth century six-light square headed (ugh!) window it replaced. If you like your churches to have been largely unchanged for 800 years or so (and who doesn’t?) then Ketton may disappoint you. There is, however, much here that is of the very highest quality and there is much of interest within. What’s more there’s a pub next door. What more could you want? Ketton’s worth the visit. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The glorious west doorway. The zig-zag mouldings are classic Norman style, but the course of pellet moulding around each of the three arches are more typical of the later Transitional period. The composition is slightly spoiled by the asymmetry of the two flanking blind archways. It seems likely that the southern archway was re-modelled to accommodate the south aisle during the early thirteenth century work. Right: Looking into the tower crossing with doorways to the two transepts on either side. Note the ill-advised re-use of a Norman moulding on the south side. The crossing arches are comparatively narrow and very pointed, belying their Early English period origins. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the west and Gilbert Scott’s Victorian window. Note the height of the arcades which make this nave feel very tall and narrow. The clerestory is, by contrast very low and its windows are contiguous with the aisle arches: not, it, must be said, the most aesthetically pleasing effect within or without. Right: The extraordinary use of Norman stonework above the doorway between south aisles and transept. Its bulk tells you that this was probably recovered from one of the original crossing arches. The dog-leg appearance is because it seems to comprise two straight pieces butted together! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking again towards the east end. Above the crossing arch is a Norman doorway leading from to the bell ringing chamber. The wooden stairway is from a spiral staircase within the church’s structure. I have to say that I haven’t seen a satisfactory explanation for this doorway (or perhaps I’m being obtuse). Is it a remnant of the allegedly unfinished tower of 1190? Note the two visible rooflines. The higher of the two is presumably, again, that of the 1190 nave. On the eastern side of the crossing is another round-headed opening; this time a glazed window and looking like it might have been re-modelled. Centre: T.G. Jackson’s neo-Gothic east window in Early English style. Right: The east window from the outside. Whereas within the church it would be difficult to tell that the window was not original, from the outside there are tell-tale signs of new masonry. It somehow looks “wrong”. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Traces of mediaeval painting still visible on the western crossing arch. Right: The window to the tower above the east crossing arch. The rather pretty chancel roof painting dates from the Victorian era. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The fourteenth centiury ont has a design composed of early Decorated style window tracery imagery carved rather tentatively into the stone. Centre: The chancel roof. I often feel that this is where Victorian restorers often added to churches. Sure, mediaeval originals - where they survive - are usually beautiful too. Some might find this roof a little garish, perhaps; but our ancestors would have delighted in the vibrancy of the colours available through modern paints, I feel. That said, those angels are unforgivably naff, aren’t they? Right: The south door in simple Early English style dates from the construction of the south aisle during the thirteenth century building phase. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman doorway to the bell room. Centre and Right: There are some nice poppy heads omnthe seating at Ketton that are overlooked by other commentators. In the usual fashion human faces have been defaced during the Reformation but the efforts seem to have been a little half-hearted compared with at other churches. The gryphon on the right has a delightfully mournful face! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four more poppy heads . Who is that knight carrying a shield? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

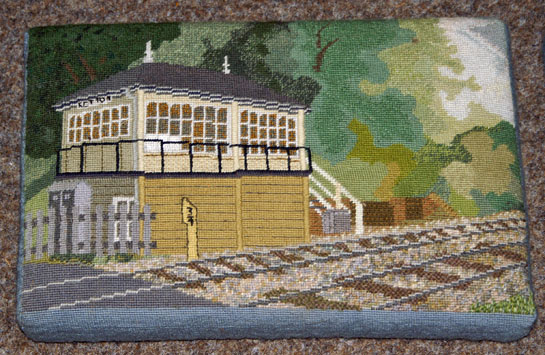

Left: I found this peculiar sculpture sitting at the bottom of a column. I have no idea what it is! Right: Ketton has a busy freight railway line - unsurprisingly considering the importance of the cement works. At Ketton, as at some other churches, kneelers have been embroidered by local people to depict life in the village. I am rather fond of this. The mediaeval population also did not see their church in a totally religious context as the many secular external carvings - and bench ends such as we see above - demonstrate. See also the wonderful collection at Ickleton in Cambridgeshire. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The tower and its bell openings are of the finest quality. In 1180 we had huge Norman pillars, rounded arches and a very rude yet vibrant style of carving. Only fifty years later we have beautiful compositions such as this. Look at the beautifully turned clusters of pillars, each carved as a separate entity. Interestingly, here as on so many Early English towers, the tradition of decorated moulding lived on within the bell openings. It is now much more refined, however as our masons replaced axe with chisel and bolster. Note the way some of the columns are continued as far as the tower parapet giving a sense of added height. Right: The spire came a hundred years later and boasts several boisterous carvings. The Early English period was one of restraint and elegance before the High Gothic period (comprising Decorated and Perpendicular styles) saw a return to the vibrant carving of Norman times. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The tower here does boast a corbel table, a real hangover from the Norman period. Note particularly how some of the faces “eat” the pillars that have been projected upwards from the bell openings. I haven’t seen this anywhere else except on Norman rose windows such as at Patrixbourne in Kent. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Left: A view of the tower from its north east corner. Note the beautiful symmetry of the two sides and the carvings adorning the bottom of the broach spire. The gabled openings on the spire are called “lucarnes” and are a characteristic of broach spires. Centre: In the corner facing us on the picture left another slender masonry column extends upwards to support the base of a saint or other holy figure. The column itself is in turn supported by another (unidentifiable) carving. Other sides have similar devices and, again, I do not recall seeing this composition anywhere else. Right: One of the grotesque figures from the spire. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Footnote |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

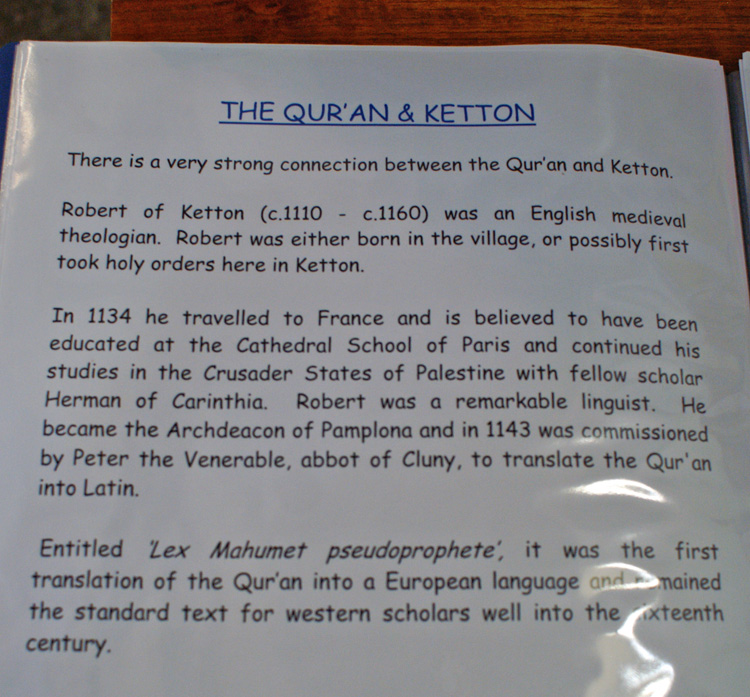

The church has a notice showing this fascinating connection between Ketton and the “Qur’an” (that’s the Koran to we westerners). I was feeling a bit lazy so rather than writing it all out, I thought I would reproduce the picture I took. Hope they don’t mind! |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||