|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

Dedication : All Saints Simon Jenkins: *** Principal Features: Ancient Town Church with Interest Everywhere |

|

|

|

|

added and the Newark was extended eastward with the Vernon Chapel to produce the rather enormous south transept we see today. The tower is part of the 1841 rebuilding program, necessary because the original steeple was buckling to the point of near-collapse - doubtless caused by the usual centuries of adding extra weight to Norman foundations never designed for it. This could have meant demolition of the church and complete rebuilding but in the event the whole of the north and south transepts and the crossing were taken down, revealing the Anglo-Saxon stone displayed in the porch, although a lot was reincorporated into the reconstruction. The replacement tower might best be described as “vaguely fourteenth century style”. So all in all it is all a bit of an architectural hodge-podge. It has, however, much on interest. Apart from the fragments I have also mentioned there is an Anglo-Saxon cross shaft in the churchyard. The fourteenth century font is fine and unusual. There are three mediaeval misericords and a whole collection of Victorian ones that are so faithful to mediaeval designs that I confess to having been taken in by them and I suspect they are faithful copies of what were there originally. There are some imposing monuments if you like that sort off thing, including the Vernons of Haddon Hall. It all makes for a quite long and interesting visit. Enough of my wittering: let’s get on with it. |

|

|

|

Left: The view to the west end. Top left and right you can just see the blocked Norman doorways that would have led to the two planned west towers that were never built. The westernmost bays of the aisles were originally Norman but now remodelled. The aisle walls are probably Anglo-Saxon below the clerestory level. Right: The north west corner, clearly showing the unused Norman tower doorway. This aisle is conspicuously wider than its southern counterpart. |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view to the east. The crossing arches are lofty but we must remember that the crossing was completely rebuilt in the nineteenth century. Centre: The chancel is unusual in having two window spaces. They are late thirteenth century in common with the rest of the chancel and the unusual and aesthetically not very successful arrangement is possibly a result of their being on the cusp of early English and Decorated style architecture. Had they been twenty years older we would have expected perhaps a plain but dignified triple arrangement of narrow lancets. Twenty years later we might have a single large window with geometric tracery. Instead of which we have two windows of EE shape but much larger and with the simple “y” shaped tracery. Note to the right the triple sedilia. Also banks of choir stalls of which more anon. Right: The imposing south side of the vast south transept. The doorway is Early English in style - having pre-dated the chancel by some decades - and it was faithfully rebuilt in the nineteenth century, although there is no escaping the look of “newness” still visible in the facing stonework. The large roundel between the two arches looks like a possible Victorian elaboration and the window above was surely either remodelled in the fourteenth century or in the nineteenth. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Left: The church from the south west. To the right is the great bulk of the south transept that - remarkably for a parish church - has a battlemented clerestory. The windows are Early English lancets that are precisely what we would expect to see with the thirteenth century date but we cannot know to what extent they are original given the extent of the emergency Victorian rebuilding. I think we have to say that everything we see at this church encourages us to believe that it was really a case of “take apart and put back together again” because we don’t see any of the fripperies and confections we might otherwise have expected. Centre: The church from the west with its obvious Norman west door surmounted by what looks like a fourteenth century window. Note the blind niches to left and right. and clear evidence of more than one changes to the masonry at this end. Right: The West doorway is one of the remaining Norman features. This door and its ironwork are very fine. The motifs are very fine and we can see similar designs at Skipwith in Yorkshire and at Rochester Cathedral. The crosses with bifurcated flourishes are a shared motif. These are termed “moline (or miller’s) crosses” and resemble the cross of St John. It is possible that the arms represent the with beatitudes but I am always a bit sceptical about these attributions because every number between one and ten seems to have some significance in Christianity (Holy Trinity, Four Evangelists, Seven Days of Creation and so on (see Elvis Presley’s “Deck of Cards”...) and it is too easy to put unintended significance on such things! Even more interesting is the rather odd square design at the top of the door. Some representation of St Brigid’s Cross are shown with inwards-curling flourishes - see again Skipwith and Rochester Cathedral - and this is believed to be a symbol of good fortune. The intertwined central design is missing but this would be a difficult commission for any smith so maybe he simplified it? Anyway, it seems likely that at least the ironmongery on this door is original Norman. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

Now we enter the south transept aka “The Newark”. This bit is the The “EvenNewerwark” because it is the Vernon Chapel that was added to the east of the the twelfth and thirteenth century transept to make a very large extrusion indeed both in terms of both width and length. Originally the new space had two or three chapels but these were victims of the Reformation so it was taken over as the mortuary chapel of the Vernon and Manners families. Left: Sir Thomas Wendesley who was killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. Thomas was an adherent of Henry Bolingbroke who overthrew the lousy King Richard II in 1399 and was proclaimed Henry IV. Naturally, a few “local difficulties” followed and Henry had to confront a rebel force led by Harry Percy - the legendary “Harry Hotspur” - at Shrewsbury. It was a battle that could have gone either way and it was the first time the English (and Welsh) longbow dominated a battlefield. There were to be many more. An arrow killed Hotspur amongst others during an attack on the King and his standard - allegedly because he opened his visor which was a bloody stupid thing to do! The King lost more men than the insurgents but it broke the proud Percy family - Earls of Northumberland - for good. Wendesley (or Wensley) was on the right side which did him little good. A more grisly fate fell to Sir Richard Vernon who was on the “wrong” side and was captured. He was hanged, drawn and quartered in Shrewsbury and his severed head publicly displayed. Henry didn’t believe in messing about. Right: An altogether more tranquil grouping of Sir George Vernon (d.1567) and his two (non-concurrent!) wives, Margaret and Mawde in an alabaster tomb. |

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

Left: The imposing wall monument to Sir George Manners (d.1623), his wife Grace and ten children one of whom (upper row left) died in infancy. For the time that was a pretty good survival rate, it must be said. Centre: One of two Anglo-Saxon era crosses in the churchyard, although oddly the Church Guide (oddly), Simon Jenkins (predictably) and Pevsner mention only one. This at the east end of the church. is the one that gets the mentions, presumably because it is historiated. It’s probably worth mention that this cross would be an Anglian one, not a Saxon one. We all fall into the trap of attributing everything to the Saxons! Anyway, it is eighth or ninth century depending upon who you believe. Unsurprisingly, there is little consensus as to the meanings of the motifs, not even as to whether they were Christian or Pagan or (most likely in my view) a mixture of the two. The head of the cross on this side is generally believed to be a crucifixion scene but it’s not obvious to me. Right: The north face of the cross. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

These three pictures and Left Below: The second pre-Norman stone is tenth century and is known as the Beeley Stone because it was dug up there during the nineteenth century. Although scholarly focus is all on the Hassop Cross, I find this one much the more interesting of the two despite the fact that all the decoration is stylised. This is because it is a rare example of a cross which (apart from its decapitated state!) shows us a complete decorative scheme with very little weathering - a rare thing indeed. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

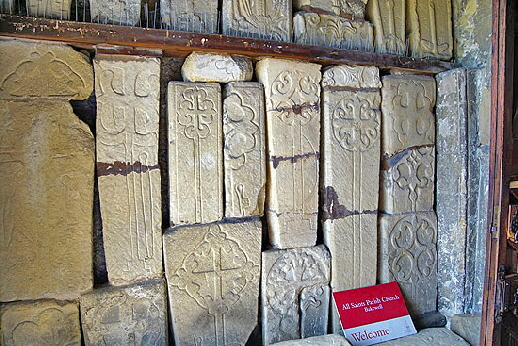

Left: See above. Centre: There follows several pictures of the astonishing collection of pre-Conquest stones that are collected within the south porch. They were found during the Victorian rebuilding of the crossing and transepts. I don’t know what they were doing there; perhaps they were used by the Normans as part of the footings? They are strong evidence for Bakewell as a housing a “school” of sculpture. That does not, mind you, really explain why there there is so much here: one rather assumes that the workshop did sell their output to other locations! This particular grouping is interesting in that it shows quite a few styles of actual crosses, including (bottom right) a “chi-ro” symbol. Right: Here we see a lot of examples of interlace work gathered together. The stones above seem to be fragments of Norman work. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: More interlace work. It is well executed and some of it is very “fresh” looking, giving us an idea of the delicacy of this art - created with primitive tools. Note, for example, the fragment upper right in this picture. Centre: This piece caught my eye, Right: There is also a massive collection of grave slabs gathered here (see pictures below). This is one of two that caught my eye for having a cross head that is the “circle interlaced by arcs” that Mary Curtis Webb identified as a symbol of Plato’s Cosmos. The symbol is a rare one but is found across Europe and quite often - but by mo means always - associated with funerary goods - see Northampton St Peter and Mary Curtis Webb in Europe. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

The grave slab collection. Presumably many of these were displaced from the churchyard when the Norman church was built. One can readily imagine, however, that if there was a commercial masonry workshop in Bakewell that grave slabs would be very much their stock in trade. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another example of Plato’s circle interlaced with arcs. Right: Amongst the mass of carved interlace work there are also historiated designs including this one - it looks Norman - of a beast - a Lion? - with his tail curled round his body and over his back. Oddly it is has the legend “marcus” clearly visible beneath it. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

The font is dated to the fourteenth century. That, I presume is because of the ogee arched (ie curvilinear) tops of the surrounds for these apostle figures. Were it not for this, I think we would be assuming a Norman provenance because the apostles are a regular theme on Norman fonts and these figures are of similarly unsophisticated craftsmanship. Well, here’s the thing. Look closely at the heads of those surrounds. Are they, in fact, ogee? I don’t think they are I think it is simple cusping that is there to “support” courses of (laurel?) leaves. Are we really to suppose that because the ogee arch was not found in English architecture until the fourteenth century that this decoration is necessarily fourteenth century too? It looks rather to me that the sculptor was just trying to be creative with his patterns. So who says it is fourteenth century? Well, I am afraid it was Sir Nikolaus Pevsner and I rather suspect that as usual everyone has seen his views a being (pun intended) the gospel, I think he was wrong. I think this font is Norman within a church that was...er....Norman! Its damaged panels even give it the look of one of those innumerable fonts that were cast out of the church at the Reformation (all that idolatrousness!) and were retrieved from churchyards, ditches and farmyards retrieved later. Do feel free to email me and to tell me that I am wrong and why. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

I am not very good at identifying the saints at the best of times and the weathering here makes identification even more difficult so I am not going to guess. Left: Is probably St James with a pilgrim’s staff and hat, Centre: Well he’s holding a sword possibly? I think this is probably St Matthew and that his other hand is holding money bags as was a tax collector (hiss!). Right: St Peter with the most enormous key. You can always bank on Pete to be recognisable |

|

|

|

|

|

Left: This is surely Mary as Queen of Heaven. Centre: Christ in Majesty. |

|

|

|

Left and Right: The Victorian choir stalls that have (you can see them showing) the faux-Mediaeval misericords. I hope the choristers realise tht they are following in the tradition of the poor old monks who would really have needed these comforts for their arthritic old bones as they performed endless masses. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So to the misericords and let’s start with the mediaeval ones. Left: A winged dragon. The left supporter is a grotesque with a human head, the right is a meticulously carved mermaid. I always think the carvers liked to carve mermaids for two fairly obvious reasons...! Right: A dragon with a human head and with supporters in the forms of female and male heads. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Two grotesque dragon-like figures flanked by stylised flowers. Right: So to the “modern” misericords. I do not think these misericords came out of the mind of a Victorian carpenter. The themes are so obviously mediaeval and, for their time, petty incomprehensible that we must assume these were copies of misericords that had been in-situ previously or at least copies of ones the carpenter had seen elsewhere. Such a quantity of stalls indicates that the church would have had collegiate status. That would have gone during the Reformation so it is fortuitous that the stalls were not just discarded subsequently. The Victorians were a pretty buttoned-up lot so it is good to see a carpenter doing his own thing and “damn you eyes” in the way his ancestors would have done half a millennium before. This splendid example has a lion with one head and two bodies eating a serpent. Men with wings and hooves flank him. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This face-puller seems to have asses ears. He is flanked by geese, the right of which is preening. Right: A dragon flanked by leaves. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A sword-wielding knight battles with a dragon flanked by two dragons. Right: An angel. Yawn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A wyvern and a dragon supported by two human heads. Right: A cockerel. To his left two chicks re perched on a barrel. To his right is a cock preening. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Two animals face each other in an unusually amicable posture. Stylised foliage are the supporters. Right: One of the most recognisable images in mediaeval iconography: our friend the green man. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A man emerges from an egg, miraculously armed with a knife with which he defends himself from two dragons. The one on the left looks particularly hungry. Right: No set of carve stalls would be complete without an image of a pelican in her piety. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another angel. Right: A very curious one. A grimacing head has what might be especially luxuriant foliage issuing from his mouth. The supporters are very interesting. On the left a man carries milk pails with a yoke. On the right is a cow with three rotting teeth shown above him! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An angel with a book flanked by two grinning visages. If you look at their faces and the rather embarrassed-looking angel it’s rather as if they have caught reading the “naughty bits”! Right: A face puller. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: So you are wondering if these miseries are really faithful to the originals? Well flanking this rather jovial dragon is another dragon and... some bloke having a poo! There is no two ways is there? I expect Lady Fotheringham-Gore never looked at the misericords which is probably just as well. Again, somehow the dragon’s face seem to tell you that he knows what the bloke (is a that a crown he’s wearing?) is doing. “What’s he like?” Right: A crowned lion facing a hart. A deer is scratching himself on the left. On the right is another lion. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A whole raft of stone coffins leans nonchalantly against the church wall. Right: The spire here is an imposing one. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||