|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The visitor might be first struck by the peculiar top stage of the tower which sits at a forty-five degree angle to the stages below. It was added in the early fifteenth century and is unique in England. It was not built thus for the sake of being “different”, however. It is much more likely that the original crossing below was already showing signs of strain. The diagonal configuration will have helped to ensure that the arches did not spring apart under the added weight. The configuration has changed little over the centuries. It was built on a true cruciform plan: that is with a central tower and crossing at the centre of two transepts, the chancel and the nave. The chapels that flank the chancel also date from the that time. The south side is known as the Town Choir and this rather small space was that reserved for worship by the local people. The north chapel is now known as the Piper Choir and is little changed. The chancel is very much the beauty of this church. Rather unusually it has a triforium - a galleried intermediate space between arcade and clerestory - that is not mirrored within the nave. This is a very pretty feature with a long run of wide (but low) pointed arches supported by neat and slim columns. The whole architectural composition at this east end is, in fact, a text book example of the transition from Norman to gothic styles. The triforium is a lovely piece that would be quite at home in an Early English style church. Similarly, the crossing arches are pointed but plain. The arches leading from chancel to Town Choir are, on the other hand, round in the Norman style, matching the south doorway. All of these round arches, however, have decorative courses of simple geometric designs that eschew the zig zag and beakhead tropes of the Norman era. To add to the glorious ambiguity of it all, the arches leading from the nave to the side chapels via the transepts have narrow pointed arches with courses of decoration that would have been perfectly at home on Norman round arches! The masons here had a field day mixing the old and new forms. The fourteenth century saw the expansion of the Town Choir in the Decorated style of the day. It was extended to accommodate the tomb of the first Lord Harrington who died in 1347. Meanwhile, however, the monastic buildings on the south side of the church were becoming ruinous owing to their being built on riverine alluvial land rather than on the rocky outcrop occupied by the church. The program to rebuild it all on the more stable north side also saw the addition of the top stage of the tower, the extension westwards of the nave and the magnificent east window, all in the Perpendicular style. This window probably replaced a set of two groups of three early gothic lancet windows thus more or less eradicating the Transitional nature of the exterior. This period also saw the installation of the twenty-six misericord seats in the chancel, probably in around 1450. All are more or less intact and their subject matter is fascinating. Interestingly, there were only thirteen monks as the foundation of the monastery, a mere seven in 1381 before the misericords were installed, and ten at the Dissolution. Did the twenty-six stalls point to a short-lived golden age or to a dose of wishful thinking? The church might have survived the Dissolution but the monastic chancel was probably seen as fair game for the despoilers. Thus the lead was stripped from the roof and the chancel was left open to the elements, causing damage to the surrounding stalls. Between 1618 and 1622 one George Preston of nearby Holker Hall had a new chancel screen installed. The excellent booklet about the misericords says that at this time the minister was expected to conduct evensong and matins in the nave so that he could be seen and heard by the parishioners but also to carry out Holy Communion in an area screened from the rest of the church. That the screen escaped intact from the Cromwell’s troops is something of a miracle. Amongst other things they destroyed the organ. New canopies were installed over the misericords. Preston paid for many other improvements, including a new roof. His funds were supplemented by substantial contributions from the parishioners. The screen is adorned with a lot of entertaining iconography that seems to nod to a period two or three hundred years before. This might be explained by the church’s belief that a lot of the timber was re-used. Altogether, the woodwork here is a glorious thing for those that have eyes to see. Or who pay the paltry sum of óG1.99 for the explanatory booklet. Why anyone would look around the church and not bother with it is quite beyond me. Because if you are not interested in the bizarre misericords and other woodwork you certainly ain’t going to understand the styles of architecture, are you? Finally, the church retains substantial fragments of its original mediaeval stained glass. If you have read this web page and visit the village without visiting the church - with your eyes OPEN - than I don’t know why I bother! |

|

|

|

Left: The church from the south west showing the oddly orientated top stage of the tower. Th south transept is a mighty structure with two Perpendicular style windows. I am not sure that upper one is an unqualified success! Note the absence of any of the original Transitional windows. In the background you can see two blokes worn out from looking at the misericords. Right: Another view of that top tower stage. Note the huge bell louvres improbably arranged in Perpendicular style. The church is not unduly complex in ground plan but the various little additions and the battlements contrive to make it all look very complicated! |

|

|||||

|

|

||||

|

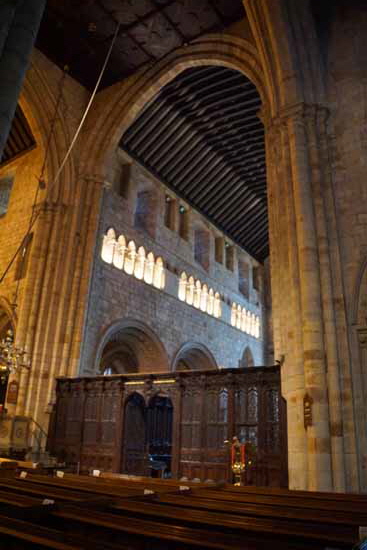

Left: The south doorway is classic Transitional style. Grotesque and historiated sculpture is out. Geometry is in. The arch is round headed but the chunky door supports are now replaced by clusters of slim columns. Centre: The casual photographer will always have problems in Cartmel Priory where the large internal space illuminated with atmospheric orange lights. I speak after four separate visits! This is the view into the east end from underneath the huge central crossing. The fifteenth east window is magnificent and a masterpiece of the Perpendicular window style. Right: Here you get some idea of he colossal proportions of the crossing and the chancel to its east. Just look at the number of columns clustered at each corner. The seventeenth century screen is quite dwarfed by it all. Beyond the arch you can see the three stages of the chancel: arcade, triforium and clerestory. Note particularly the way the early gothic triforium with its delicate arches contrasts with the still-rounded Transitional arcade. Above those, the original pointed lancet clerestory windows have been replaced by nasty rectangular ones for which the word “undistinguished” is perhaps too lavish praise. Patchwork replacement of windows with little regard to what is already there has blighted thousands of English parish churches over the centuries. Sadly, the Priory is just another example. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking west through the seventeenth century chancel screen. To left and right we have our first glimpse of the choir stalls and their misericord seats, Right: Another view of the south doorway. Note particularly the oddly-exaggerated extension of the hood mould to the right, creating a serpent. It is as if the masons couldn’t quite bring themselves to cast off their Norman sculpting traditions! There was probably the same conceit on the left side but rebuilding seems to have caused it to be “lost”. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three rather soft-focus shots that attest, I fear, to the challenging lighting conditions here! Left: The view to the west is very “vanilla” compared with the glories of the crossing and chancel. Centre: Looking from the north aisle through the transept to the north chapel. Here we see that the aisles are surprisingly narrow for such a large church, retaining their original late twelfth century proportions. The arches are superb examples of Transitional work, showing sophistication in the design of the columns as well as lightness and tight jointing of the masonry itself but still with the legacy of rather Norman-looking decoration. Right: Inside the south chapel - the “Town Choir” - we see the only examples of pre-Plague Decorated style windows dating from the expansion of the chapel to house the Harrington tomb. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking at the north side of the chancel with its triforium. Oddly, little is known about the use to which triforia were put. It is quite a complex and expensive feature that you will see only in cathedrals and monastic buildings. Visually, it is satisfying and certainly adds grandeur. It has been suggested, rather lamely, that triforia may have allowed certain rituals to be observed. Perhaps it was a way for the privileged clergy and monks to find their way around the building without mingling with the riff-raff below? At Cartmel, however, the triforium is only in the chancel which was exclusive to the monks anyway so it is perhaps even more of a mystery. Centre: The south transept with the Town Choir to the left. Here too we see traces of the triforium that was seemingly blocked to allow the insertion of a large Perpendicular style upper window. It is not clear why a Romanesque doorway became a large gothic niche but I am guessing it might have been the original “night stair” by which the monks would have descended to the church from their dormitory when the monastic range was on the south side. Right: The rather odd-looking Perpendicular style windows in the south transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south chapel is where the church stores most of - but but by no means all - its clutter! This view is from it into the chancel, showing the two Transitional round-headed arches. Right: The wooden ceiling of the crossing with hanging bell ropes. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Transitional capitals in the chancel. Right: Amongst the many things stashed away around the church is this pretty font cover of...oooh...I wonder what date? The Church Guide shows it in-situ so I suppose it was being stored here temporarily, |

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

The Harrington tomb from (left) within the Town Choir and (right) the chancel. This is not its original position. It was probably freestanding at the west of the Town Choir where the whole composition could be more easily appreciated. Unfortunately its repositioning led to the mangling of one seat of the fine sedilia and probably the total loss of a third. It is a very fine piece in the Decorated style |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

Left: Detail on the north side of the Harrington tomb. Right: Situated in the north west aisle is this much more recent monument to Frederick Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire. He was William Gladstone’s Secretary to Ireland and was assassinated in Dublin in 1882 in an outrage known to the history books as the Phoenix Park Murders. It was the work of Thomas Woolner who was, so the Church Guide tells us, the only sculptor member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. |

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

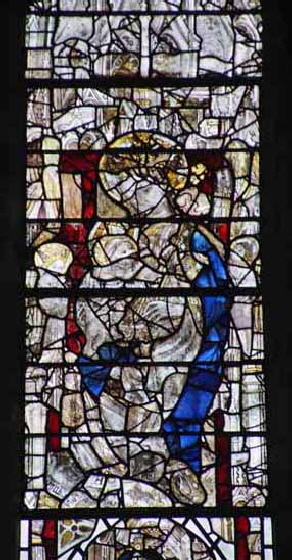

Left: One of the two chancel screen doors. Centre: Only remnants of the east window’s mediaeval stained glass survive. This is the central panel. Right: The central image is of Mary cradling Jesus. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: An archbishop, probably William of York. Centre: John the Baptist. Right: Figures of saints. Top right is clearly Andrew with his saltire cross. Bottom right appears to be St Matthias, Judas’s replacement, who is carrying the axe or halberd with which he was executed. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Various glass panels from the Tree of Jesse window (depicting Christ’s supposed lineage) in the east window of the Town Choir. Second left is King Solomon. |

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left: One of two marooned corbels in the Piper Choir (north chapel). The Church Guide says it is a dog fighting with a cat. Well the dog is a certainty, but I can only make out a very vague suggestion of a cat if I turn the picture upside down. This way up it looks more like a dog attacking a sheep or some other animal. Right: Samson killing a lion by his tried and tested method of wrenching the beast’s jaws apart. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Two more fragments of mediaeval glass |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The south side range of mediaeval choir stalls. The ornate canopies of the seventeenth century make a magnificent setting got the misericords that are the real stars of this church. Oddly, I am most excited by that long, huge plank of English oak stretching away from us that serves as a book rest. How many men have stood and rested their books there for the last six hundred years? How many monks peered down in the candle-lit gloom, freezing their extremities, their arthritic bodies crying for mercy after rising from their slumbers and making their way down the night stair? Right: The central figure over the seventeenth century chancel screen - a bizarre mix of mediaeval and classical influences. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

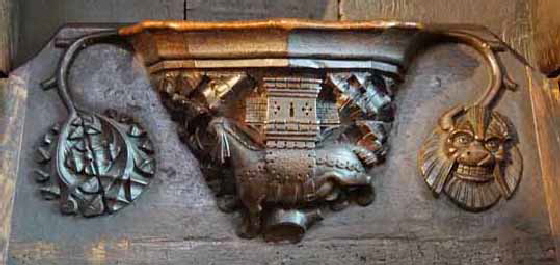

And so to the misericords! Let’s start with two old favourites of the carpentry world. Left: The Elephant and Castle. This is a particularly fine one. Of course elephants were used in warfare in ancient times, Hannibal of Carthage (in modern Tunisia) being the most famous user. Alexander the Great was said to have possibly used them as well as having been beset by them in Persia and in India. To the insular English an elephant must have been the most exotic of creatures, notwithstanding the fact that Henry III received one as a gift from France’s Louis IX. The unfortunate animal died quickly, having been fed - or rather not fed - on a diet of meat! The castle is a very elaborate one. The elephant depiction is bizarre. Right: The mermaid, complete with comb and mirror the personification of vanity and unfulfillable lust. Note the heavily scaled fish writhing on the right supporter. The Church Guide suggests it is a dolphin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: According to the Church Guide this could reflect the tradition that Alexander the Great was carried to the gates of Heaven before being told to go away for his presumption. Or that he is at the extremity of his Alexandrian empire. I don’t really understand this allusion and prefer the alternative that it is Satan enthroned. I can’t understand why Alexander would have been represented in this way. The feet and hands are clearly beastly. And he pre-dated Christ by some three hundred years so he could not have been persecuting Christians. As Satan, though, he is perfect. Just look at those beautiful dragon-like wings and that ape-like face. It does beg a question in my naturally sceptical mind. If Satan is represented so graphically in the holiest part of a monastic church, how seriously did the monks take Satan as a serious embodied anti-Christ? Right: A deer is chased into a thicket by three dogs. Christ is sometimes likened to a deer. What animal is he not likened to, you might ask? Well, how about the hedgehog pictured on one of the supporters here? The comedian Mark Harding who wrote a little book about misericords reckons it is the only one in England other than at New College Oxford. Have you ever thought, by the way, how dumb the name “New College” is? Six hundred years on? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another of Cartmel’s stand-out misericords. An ape clutches a bottle of urine, a barely-veiled satirical allusion to the uselessness of the mediaeval medical profession. The ape was a symbol of deceit. Right: An interesting carving. If you look closely he has noses protruding from left and right of his face. It is sometimes called the “Trinity Face”, possibly reflecting the notion of God in three forms. This form has appeared in many cultures, however. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This close-up perspective gives better appreciation of the Satan Enthroned misericord. Note the dragons hiding under his wings. Right: A closer look at the ape with his urine flask. He seems to be sitting on a privy so this, it seems, is fresh urine! Well that would be a relief to the customer. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Close up of the elephant. It is a fanciful depiction, to say the least. The creature has a mane and carthorse-like legs on massive hooves. His ears are ribbed like a dragon’s wings, The trunk is trumpet-like. Right: This photograph, kindly supplied by Bonnie Killingback, is of a misericord at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. It has apes with urine flasks on its supporters similar to the one at Cartmel. Indeed, the right hand supporters leaves nothing to the imagination as the ape happily fills the flask with fresh “medicine”! The central motif shows two bears at a ragged staff, recalling the ceremonial badge of Warwickshire, the county of my birth. I am glad they chose the bear, rather than the apes! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

THE REMAINDER OF THE MISERICORDS CAN BE SEEN BY FOLLOWING THIS LINK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Corner carvings between the choir stalls. Right: Unicorn motif on the chancel screen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Three of the carved stall armrests. They show the wear of the centuries. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Carved seat in the chancel. Centre: Looking through the westernmost arcade of the north arcade to the Cavendish monument beyond. The hatchments are of the Lowther and Cavendish families. Right: The north door. It is interesting to compare the north door with its counterpart to the south. This doorway has a gothic pointed arch and the decoration is limited to a single course. They were probably built within a few years of each other yet are so very different, marking the febrile architectural environment in England around the end of the twelfth century. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

And Finally.... |

|

My Anglo-English friend, photography fiend and fellow church-crawling fanatic, Bonnie Killingback, sent me these further pictures of apes with urine flasks as well as the example at All Saints, Straford-upon-Avon above. |

|

|

|

Left: Wooden panel at Abington Park Museum, Northants. The ape at the top is busy filling three flasks. He seems to have been chained up. Right: Misericord at St Andrew Church, Norwich, |