|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

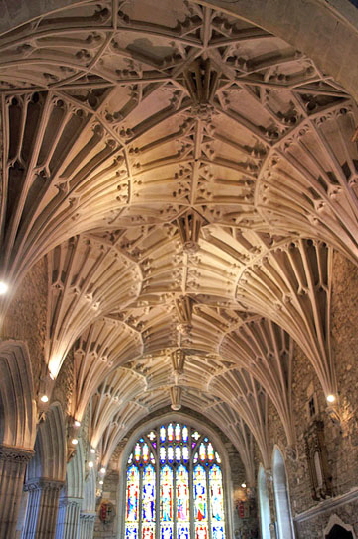

because parts of the earlier Early English church may indeed have been incorporated and there was a wish to keep continuity of style. If so then Grandisson was paying far more attention to architectural consistency than was usual amongst mediaeval patrons who generally wanted the latest style in flagrant disregard of aesthetics! The east end is also anachronistic. Its window is an arrangement of no fewer than eight lancets all surmounted by a triple niche arrangement. We are not to be misled, however: the lancets are cusped and the niches have ogee curves (that is, they are s-shaped) which betrays their fourteenth century pedigree. Nevertheless, I think the style of this church would at the time have been what we now call “retro”! The slightly un-English look of this church is accentuated by its having two towers - one above each transept. This is a rarity in English parish church architecture. It was much more the norm in great French churches and cathedrals and even then usually flanking the west front. Grandisson, however, is believed to have been aping the grandeur of Exeter Cathedral which itself has twin transept towers. Remarkably and gratifyingly, little has changed since the church was originally built. The exception is the famous and spectacular “Dorset Aisle” on the north side of the church. It is so-called because it was sponsored by of Lady Cicely Bonneville in 1520. Herself a direct descendant of Bishop Grandisson’s sister, she was married to the Marquis of Dorset. .Rather oddly, it was tacked onto the side of the original northern aisle which is in perfect symmetry with its equally narrow southern counterpart. Its glory is its fan vaulted ceiling, surely the finest in any non-Cathedral church in England. It is undoubtedly beautiful so it is perhaps churlish to suggest that it is also somewhat incongruous! The nave and chancel are both soaring structures with magnificent rib vaults. To my eyes the Dorset aisle is a little bit squat and overall detracts from the harmony of the place. both inside and out. The overall impression of the church is of its being a little bit muddly. In reality, if you look closely, it is only the Dorset Aisle that mars almost perfect fourteenth century symmetry. Even the towers are symmetrical: don’t be misled by the addition of a squat spire on the north tower. With its “mini-Cathedral” proportions you would expect the interior to have much of interest and you would not be disappointed. Because of my own preoccupation with mediaeval carving it is the roof bosses that excite me but there is plenty here for everyone. The Dissolution of the Monasteries also saw the disestablishment of the “colleges”. It is not difficult to understand why. Canons had by now become embroiled in the chantry system whereby priests were paid to chant masses for the immortal souls of rich patrons in order to shorten their time in purgatory. The Reformation put paid to that practice and not before time, you might very well think. Either way, at Ottery in 1545 it also resulted in the demolition of the college buildings of which no trace is now to be seen. This was just a quarter of a century after the Dorset Aisle was built. |

|

|

|||||||

|

Views of the church from (left) the south-east and (right) the north-east. Note the nave and chancel windows are also in a kind of Early English/Decorated transitional style. Three cusped lancets sit within a stone framework. Note the same model is used for the east window, albeit on a larger scale. The clerestory windows are curious. For all the world it looks as if their lower halves have been obscured by the later additions of choir aisles and vestries. In fact all of these are contemporary and the clerestory windows were constructed with their rather dumpy, cut-off look. Stylistically they match the chancel windows but their proportions look all wrong. Note the abundance of single lancet windows on both sides of the church. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

The nave looking towards (left) the east and (right) the west. There is nothing archaic about the arcades (no that’s not a pun!). The arches are complex in cross section but elegantly-shaped. There is just tiny capital on each of the inner shafts. For their time these must have been the height of modernity. Note the beautiful light gray stone that gives luminosity to the interior. Note also the matched canopied tombs to south and north. |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

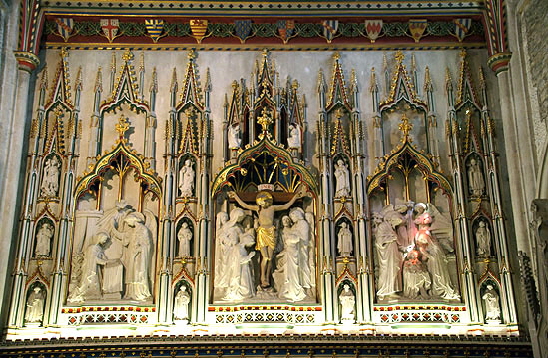

Left: The altar screen. This is not completely original. Ottery did not escape the depredations of the Reformation. The niches were emptied of their statues and were filled with plaster so as to leave a blank face. Of course, all of the gilt and paintwork was also obliterated. In 1829 the niches were re-opened and the heraldic shields were re-painted. Only in 1934-5 were the sculptures replaced by Herbert Read of Exeter and all of the paintwork restored to its former glory. Right: Beyond this screen is a small ambulatory area and beyond that is a Lady Chapel that is the easternmost part of the building. This reinforces the mini-cathedral nature of this church. In most parish churches a lady chapel would be found at the east end of an aisle. You have to remember, though, that being built as late as 1338, Ottery was able to incorporate the chapel into the building rather than shoe-horning it into an existing one. |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: This is the west screen of the Lady Chapel looking towards the west: behind it you are seeing the ceiling of the choir. Note the elaborate cusping of the arches - they are almost Moorish in appearance. Again, the interior of this church was bang up-to-date. Right: The view from the choir looking towards the west. This would have been the area the canons would have used for their daily devotions. Whereas the exterior of this church was vaguely “retro” you can see that the interior has hints of the Perpendicular style with its sweeping vertical lines which would transform (often not for the better!) English parish churches. The style - as is the case for all architectural styles - did not emerge overnight. The first English examples were at around this time and it is not surprising that such a rich church would itself exhibit avant-garde touches. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The north transept. From inside you would not be aware that above the ceiling is a tower. Note the four lancet windows very much of an Early English style but not in an Early English configuration. To the right you can just see the five-light lancet window arrangement, very much in the Early English tradition and repeated on the south transept. Note the elaborate and beautiful ceiling vault. Centre: The narrow south aisle to the choir. The vaulting here is steep to accommodate the aisle’s narrowness. At the east end is yet another lancet window. Right: Part of the north arcade showing the squat clerestory windows. They look much less peculiar from the inside than they do from the outside. An empty niche occupies the space between arch and window. One presumes that they contained statues of saints and apostles before the Reformation. |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: Well here’s a nice little quiz question for you. The north transept has images of four mens’ faces with gaping mouths. What are they? The answer is in the footnote below. They had me foxed until the Church Guide enlightened me. And you know, I have to laugh. Take a look at that right hand picture. First of all I apologise to the church’s domestic department for highlighting their lamentable inability to brush away cobwebs one hundred feet above their heads. It seems to me that there is a market for drones fitted with little brushes to clean church ceilings. But the other think that cracks me up is the artexed ceiling! Can you imagine it? A six hundred and fifty year old church with artex? Well we have already established that this church was impervious to fashion. But honestly - artex!? |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

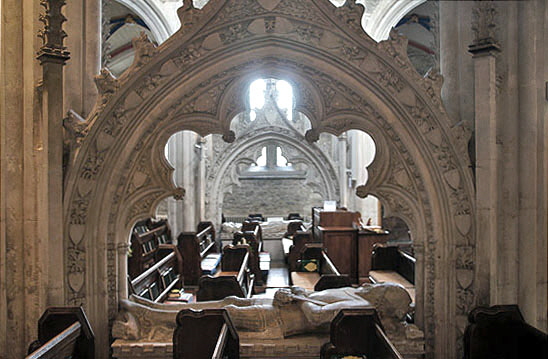

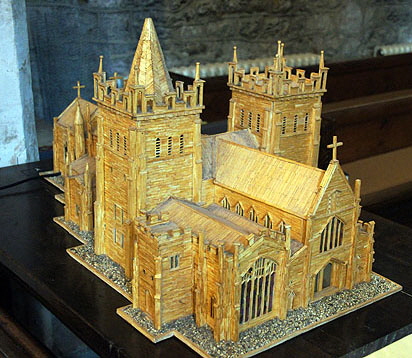

Left: The tomb of Sir Otho de Grandisson (d.1359) set into the arcade of the north aisle. Opposite you can see the tomb of his wife, Lady Beatrix. More of these anon. Right: The church displays this nice wooden model which makes it somewhat easier to get a perspective on this complex building. What is not obvious from photographs is the unusual concept of a crossing which has towers above the transept and joined by a transverse roof. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The sixteenth century Dorset aisle looking east. Note the five light window in the north transept at the top pf the picture. Centre: The Dorset aisle looking west. The perpendicular style west window pays no respect to the careful symmetry of the fourteenth century church. It has to be said, though, that these photographs do not really capture the beauty of this space. It really is a magnificent piece of work. Right: The ceiling. Note the odd projections from where the ribs meet in the centre. They look for all the world like mediaeval fire sprinkler nozzles! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

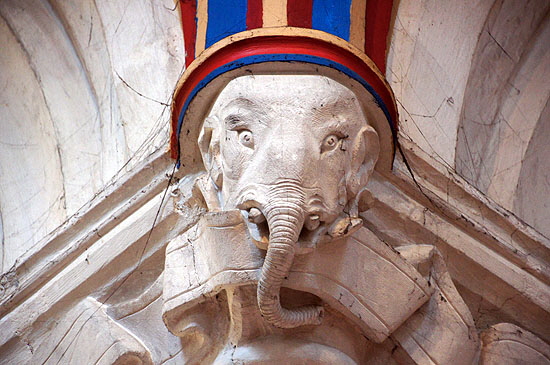

Left: The saving grace of the Dorset Aisle (and I guess I am unique in not just swooning over its beauty!) is that it is attached to the shallow original north aisle rather than to the nave. This means that the symmetry of the original church is preserved. As you can see from this picture, the arcade that separates the two aisles is of a different order of complexity from the simple elegance of the nave arches and we have some finely drawn capitals to boot. Not least (right) is this elephant which. almost uniquely I think, is by a carver who had either seen an elephant or at least an accurate representation of one! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A green man carving. Right: I am afraid that the carver was a bit less familiar with the domestic owl than he was with elephants. Those wings are all wrong, aren’t they? And those oval eyes look more human than owl-like. It’s rather cute, though. It reminds me of a something from a childrens’ story book. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north aisle chapel. It really is a tiny space. Note that lancet window at the far end and also the double lancet to the left. You can see how the Early English style simplicity on the outside is supplemented by the High Gothic richness on the inside. Centre: The south transept is much more elaborately decorated than its northern counterpart. It is not, as you might assume, paintwork but mosaic work. This dates from 1878 and is in memory of Sir John and Lady Mary Coleridge. The contrast with the scraped stonework of the north aisle creates the illusion that they are structurally different but if you look carefully you will see that they are not.. Right: The clock in the transept is of uncertain age but definitely ancient. The (excellent) Church Guide notes that there is a record of a clock in 1437 but nobody knows if this is the one referred to. The Guide also draws attention to the fact that the Earth is shown at the centre of the Universe. This then at least predates Copernicus who published his discovery that the Sun was at the centre of the Universe just before his death in the 1543. The golden sun on the clock indicates the hour. In this case it is showing 4 pm because the clock shows twenty four hours. The black ball show the phase of the moon not, as you would expect, minutes. This sphere is actually black and white (it rotates on its own axis) and I am not sure what phase of the moon a fully black face represents: the opposite of a full moon, I guess! Note the star at the “IV” point. This indicates the age of the Moon. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The funerary monument of Sir Otho de Grandissson. He was Bishop Grandisson’s younger brother. Centre: Sir Otho’s wife, Lady Beatrix. She outlived her husband by fifteen years, dying in 1379. I have particular interest in this figure - see footnote below. Right: The font was created by William Butterfield in 1850. My taste in fonts is distinctly Norman but I confess to quite liking this. The style is meant to be Norman-like with its big square bowl on a large central shaft and one at each corner. The white marble is from the famous quarry of Carrara in Italy but the rest is from Devon and Cornwall, according to the Church Guide. In which case, from my admittedly limited knowledge of geology, it is not marble at all in the geological sense: there is no marble in Great Britain. Feel free to correct me. There are plenty of carboniferous pseudo-marbles, of course, of which Purbeck Marble with its visible prehistoric shells is the most famous. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

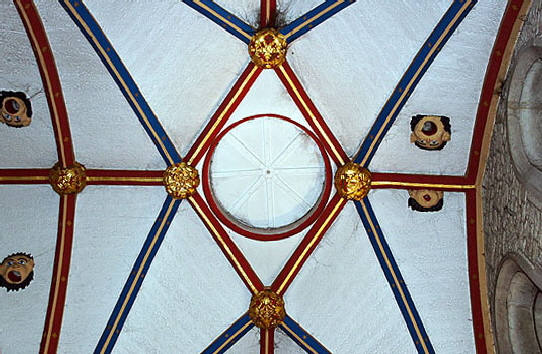

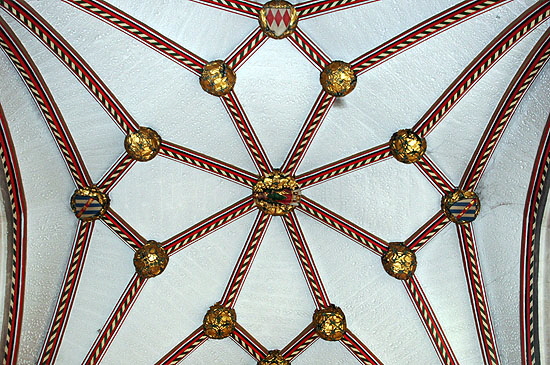

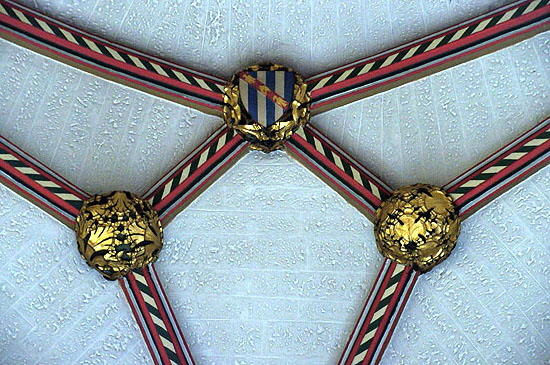

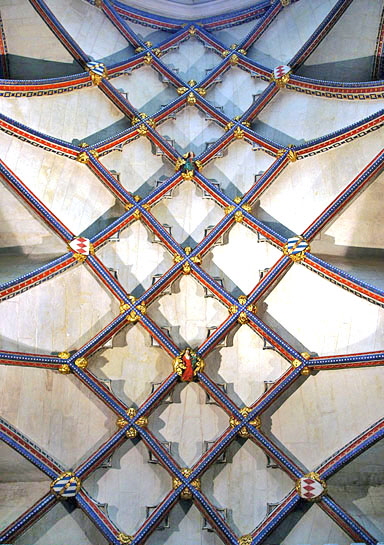

The churches of the West Country is renowned for its beautiful church ceilings and Ottery’s are simply gorgeous. These two images are of the crossing roof. The bosses are mainly gold leave designs and coats of arms. Only one boss is pictorial - see the centre of the picture on the left. This is the “founder’s boss” and is of Bishop Grandisson himself. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Founder’s Boss. Right: A portion of the nave roof, again with coat of arm bosses. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Lady Chapel roof. There are just two pictorial bosses, many of the rest being armorial shields. Right Upper: Mary and the child Jesus. Right Lower: Christ seated in majesty. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bosses of the Choir roof. There are five in all and the Virgin Mary is, again, conspicuous by her presence, reflecting the dedication of this church. Surprisingly, overtly biblical themes are not very common on roof bosses in parish churches which rather favoured the secular or even grotesque - see, for example, Dorset’s Bere Regis. This, though, was of course no ordinary church and was not intended to be so. Notice here the bold paintwork on the ribs. Simon Jenkins has this to say of the Victorian restorers Edward Blore and William Butterfield: “...their restoration was overlaid in 1977 by vigorous and controversial repainting. The colouring of the roofs, vaults and screens, though not the carved stone, is startling and distracting. Yet as at Cullompton, the intention was to reinstate the visual impact of the mediaeval church, however upsetting to the modern eye. I found Ottery’s colours grew on me”. Well, I can only say that I thought it was delightful from the off! There are obviously zealots (of whom Simon Jenkins thankfully seems not to be one) who would like to preserve the place in aspic but surely we shouldn’t be too precious about paintwork? If the mediaeval masons had these colours at their disposal they would have surely used them? Anyway, these bosses are: Left to Right: The Virgin and the Archangel Gabriel; The Virgin and Child; The Coronation of Mary; St John the Baptist. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: A mediaeval bench end. Centre: The memorial to John Coke who died in 1632 sited within the Dorset aisle. What a martial figure he looks in his armour, enormous helm at his feet! It looks more suitable for a knight at Agincourt. A peacetime soldier, though, r methinks. He was, however, a governor of the church here. When the College was disestablished Henry VIII appointed four governors and decreed that they should have “succession forever”. Edward VI, his son who was the real father of English protestantism, decided they should have eight assistants. There are twelve men still in post today forming, presumably, that beloved English institution a committee! It is said (I don’t know by whom!) that Coke was murdered by his younger brother and that his spirit descends from his niche and wanders around the church. I didn’t see it myself. Right: The lectern in the Lady Chapel is a rare surviving mediaeval example. The Church Guide reckons it is one of only twenty-one in the country. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north porch that would, had it not been blocked, give onto the Dorset Aisle. Centre: The southern aspect of the south tower. Right: The five-light east window of the south transept. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The East End. The window is a curious thing. Lancet-like it might very well-be but in fact it is also quite squat. Rather like the clerestory windows it looks like someone has lopped off the bottom section! Note the five empty niches. Notice below the east window three square images. These are in fact consecration crosses. This, as the Church Guide proudly tells us, is the most complete set in England: twenty one survive out of an original twenty-four. This gives you some idea of how relatively unchanged (one might say unscathed!) this church is. vThey are also unique because they contain figures (see below). Right: The tower parapets are surmounted by full surviving sets of grotesque figures. It’s always good to see a bit of good old English irreverence amongst so much piety! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The three consecration crosses at the east end |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 1 - Samuel Taylor Coleridge |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Coleridge was born in Ottery St Mary on 21 October 1772 and his father, John, was both vicar of the church and Head of the King’s School in Ottery a free school founded by Henry VIII. Jophn has thirteen children by two different wives - he was obviously a randy old goat - and Samuel was the youngest of the ten he had by his second wife, Ann Bowden. He was sent away to Christ’s Hospital school in London aged eight on the death of his father. He revered his father who he idealised but had a poor relationship with his mother and was rarely welcomed home. He died in 1834 of a lung disorder possibly brought on by his notorious love of opium. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Lady Beatrix Grandisson’s Headdress |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I mentioned earlier that I was particularly interested in Lady Beatrix’s effigy. This is because of the square shaped headdress that she was wearing. In my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men” where I track the work of a group of itinerant stonemasons in the East Midlands I make much of the extraordinary frequency of this style of headwear on the frieze carvings and label stop carvings. In trying to date the mens’ work, this was crucial because, then as now, fashion came and went. An expert on millinery fashions told me that this square style was a late fourteenth century fashion that was passe in the early fifteenth century. Lady Beatrix’s death was in 1379, reinforcing this dating. Funerary effigies - which are usually dated - are an invaluable source of information for students of costume. Outside of “my” part of the East Midlands (Rutland, South Lincs and East Leicestershire) this style of headdress is actually extremely rare. Why that group of masons was quite so enamoured of this style is a bit of a mystery. It certainly was not a fashion for the common people as this effigy shows. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 3 - Big Mouths in the North Transept |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Did you guess it? I didn’t to start with. And if you don’t know what I’m talking about then you’ve haven’t being paying attention. Tsk! The clue is that above the north transept ceiling is the bell loft. Once you know that it suddenly becomes clear that those mouths used to surround the bell ropes as they descended to the ringers below. If you had to convince someone of the intoxicating eccentricity of England’s mediaeval parish churches you couldn’t do better, I reckon, than to tell them about this. In a great church like Ottery where the patron was a bishop we can safely assume that the master mason was expected to consult on all aspects of overall architectural design. It’s a po-faced place really, compared with the robust pagan/Christian melange we seen in some rural parish churches. But you just couldn’t keep those cheeky masons down when it came to the detail! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||