|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The transfer to Kenilworth, however, signalled the rebuilding of the church in stone at a time when the monastic orders were inclined to invest in the parish churches they acquired. Later the monasteries would treat them as milch cows to be stripped of most of their tithes to support their extravagant and ruinous ambitions. |

|

|

||||||

|

Left: The blocked north doorway. It is rather unsophisticated in its execution and it has suffered grievously over the centuries. Right: The tympanum reveals - just about - two dragons with intertwined necks biting each others’ tails. This is presumably some sort of allegory showing that evil wil destroy itself. Above it, are two intertwined snakes. That this piece of art, over one thousand years old, has been denied any kind of protection to the point of near-obliteration is a disgrace. I’m not blaming the local people who probably have their work cut out keeping the church weatherproof for this but surely our country can afford to protect its history better? I write this the day after some lunatic paid over óG300 million for what is probably but not definitely a Da Vinci painting. God certainly “moves in mysterious ways”. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Left and Right: The north doorway capitals show valiant attempts at decorative creativity on the part of the Norman masons but these were clearly not men of artistic talent! Look at the irregularity of the interlaced work. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the east, the chancel arch and the blind arcading beyond it tell you immediately that the church is a Norman foundation. Everything you see apart from the south aisle is essentially Norman. The nave is wide for its date. Note the nice box pews. Right: The chancel arch is simply decorated with zig zag moulding. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: There has been a considerable amount of restoration work on the chancel’s blind arcading but, nevertheless, it is essentially original and, as always, very evocative of the Norman era. It is always interesting to see these blind pointed arches some fifty years before pointed Gothic windows and doorway would take Europe by storm. The idea had always been there but nobody in the west, it seems, understood its potential. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The chancel arch, north column. The outer order has an unusual “clasping” design. Vertical zig zag mouldng is also unusual in a parish church. Note the bird design which is probably a dove of peace. Centre: The south column which has a serpent on show. Right: The clasping design. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The chancel arch responds have these two carvings hidden away and easily overlooked : a snake and a bird with very odd looking claws. The Church Guide believes this to be a dove carrying a leaf (from the story of Noah) that was my own initial impression. I imagine the same mason decorated the north doorway. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Carved feet of the chancel arch. On the right you can see an elaborate and distinctly botched snake carving. They seemed to like snakes at Stoneleigh! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The view towards the west end is dominated by a rather overpowering combination of minstrels gallery and church organ. The organ dates from the eighteenth century. To the left is the south aisle which dates from around the fourteenth century and cut into the original Norman nave wall. Right: Looking into the somewhat under-sized chancel. The east window is in the Decorated style. You can see the cut down Norman columns. Pevsner saw it as proof that it was intended that it was intended for the chancel to be vaulted. Did the mason’s nerve fail them? To the left is the seventeenth century monument to Alice, Duchess Dudley and her daughter, Alicia. To the right you can just see the opening to nineteenth century vaulted tomb of Chandos, first Baron Leigh. Still further to the left in the foreground toy can see the entrance to Leigh Chapel built in the nineteenth century. This is a very “busy” little chancel! |

|

|||

|

|||

|

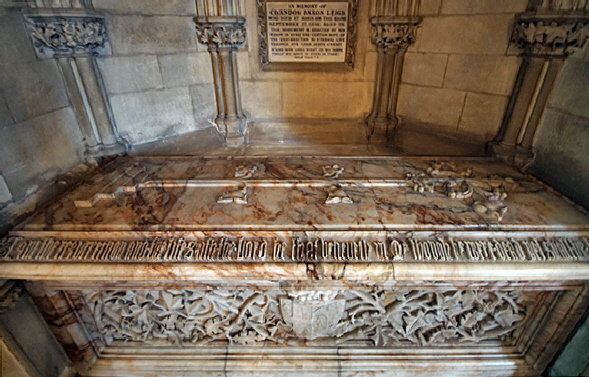

Left and Right: The alabaster tomb chest and niche of Chandos Leigh (d.1860). It is in faux thirteenth century style. To its left is the memorial to Chandos Baron Leigh who died at Bonn (what was he doing there?) in 1859. Oddly, Pevsner thought it was the tomb of Lady Leigh who in fact had it made for her husband. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north side of the chancel is dominated by this monument commemorating Alice Duchess Dudley and her daughter, Alicia. You might well wonder what became of Alice’s hubby? Duchess Dudley was the second wife wife of Sir Robert Dudley, who was the bastard son of the Earl of Leicester, also Sir Robert Dudley who was the favourite and probable lover of Elizabeth I. It seems he also inherited his father’s reckless nature and he was a noted explorer and cartographer, leading an expedition to the West Indies. Sir Robert inherited his father’s wealth, including Kenilworth Castle and tried unsuccessfully to to establish his legitimacy. In 1605 he abandoned Alice, left England accompanied by his cousin and lover, Elizabeth Southwell and went to live at the court of the Grand Duke of Tuscany.in Florence. Fascinatingly, Dudley was able to marry Elizabeth Southwell because the Pope ruled that his marriage to Alice under the auspices of the Church of England was invalid. Alice, was created Duchess of Dudley in her own right by Charles I before dying an very rich woman in 1668, at the ripe old age of ninety! Pavsner described the monument as “noble” and “too large for its position”. Well he got that second bit right !Right: The effigy of Alice (above) and Alicia. Pevsner reckoned it was probably all carved by Edward Marshall who made the monument to Alice’s sister at St Giles in the Fields in London. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: One of the fat little cherubs adorning Lady Dudley’s monument. And you thought childhood obesity was a modern thing? I cannot like this monument, I have to confess. It portends the neo-classical excesses of the Stuart era and beyond. Centre: The effigy of a fifteenth century priest, again in that busy, busy chancel. Right: The doorway to the (architecturally awful) vestry. It is in faux Transitional style that matches the restored niches around the altar. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two views of the splendid Norman font. This is an elaborate piece. It is reckoned to have come from Maxstoke Priory and its quality which is way out of kilter with the rest of the building gives this theory strong credence. The weathering and damage suggests it may have spent some time in the open. The arcading is regular. The pillars of the arcading have decorated columns. Above the apostle figures there is neat wording which shows that the mason was either literate or - far more likely - had guidance from a monk who was so .Above all of that is another series of heads, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I reproduce nine of the apostle figures here (I have the others, as well I’m sure but I’ve lost track of them all. You expect me to identify then all? Well (left) we have the ever-identifiable St Peter clutching his key to the gates of heaven. That’s the easy one done. The writing, unfortunately, is fragmentary on most of the figures and the iconography is rather obscure. If you want more detail then I suggest you go to the splendid site of the “Corpus of Romanesque Architecture in Britain and Ireland” website at http://www.crsbi.ac.uk/site/1257/. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A couple of examples of the writing inscribed above the apostles. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Poor old Stoneleigh has not been treated with much respect externally. This particular flavour of Midlands sandstone lacks the attractive orange glow of some others and is more akin to a dirty brown. What’s more it is horribly vulnerable to the weather. Most of its problems, however, are man made. Left: The church ftom the south east is marred by the extraordinary tallness of the vestry. If you follow the lighter coloured string course you can see it was originally a perfectly well-proportioned chapel. Less obvious in this picture - but very visible in the headline picture at the top of this page - is the way the nave roofline has been drastically lowered and it looks like some giant has taken a big chunk out of the top of the church. Note the east window which is in the Decorated style but which was heavily altered in the Victorian era. Right: The church from the south west. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view of the church from the north east showing very clearly the old roofline and the strange “something’s missing” appearance the church now has. The Leigh Chapel to the left with its severe rectangular look and its huge buttresses does no more favours to the church than the vestry does to the south. Right: Another view of the north side looking towards the nineteenth century Leigh Chapel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

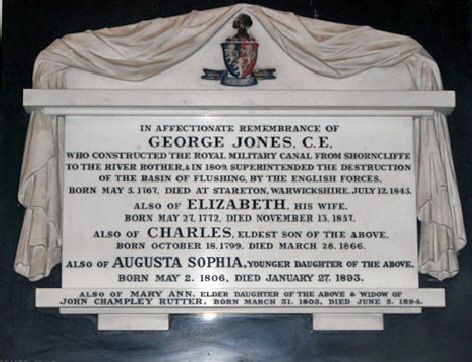

Left: The tower from the west. In fact this is the only wall of the tower that is not part of the original Norman church. The Church Guide believes this wall to be from between 1300-1350 and to have been caused by collapse or danger of collapse. Centre: The tower from the north showing a blocked Norman window. Right: A wall tablet commemorating a man with a life well-lived. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

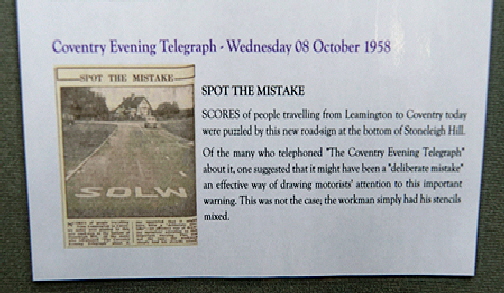

Footnote: Life in Solw Lane |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The north chapel houses a local History Society exhibition. I couldn’t resist reproducing this item. That’s what you get when you have illiterate sign painters. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote 2 - Father Petrica Bistran |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I revisited this church with a friend in January 2024, twelve years after my first visit. It was a Sunday morning and we had to wait for the 11.00 am service to finish before sidling in with that slightly apologetic air that you have when you want to just go in and take some photographs amongst people for whom this has been the week’s spiritual highlight. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

You may Download or Print these pages from the .pdf file below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||