|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

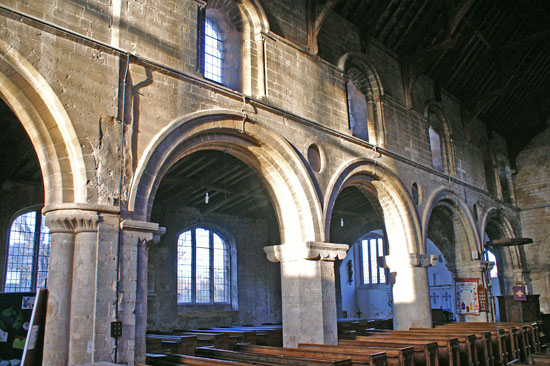

they are in symmetrical pairs across the east/west axis but each pair is different from those adjoining. The chancel arch is also Norman. The west end has a fine transitional doorway, flanked by “blind” arches. The west window has clearly been replaced by a smaller one at some time and this mars what would have been a rather magnificent west end. The aisles were widened during the perpendicular period so that the original aisle walls were lost. The south aisle still presents an attractive face to the world; the north aisle with its ugly and asymmetrical windows much less so. The Norman north clerestory is large intact, but the southern one was reconstructed between 1480 and 1560 when major changes were made to the church, including the installation of a hammer beam roof. This in turn has been changed many times so that only three flying angels remain from what was probably a highly-ornate feature. The original Norman chancel has been long since lost. Today’s chancel is Victorian. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: View east towards the chancel. Note the size of the columns and the cushion capitals matched in pairs at north and south. Right: The view towards the west end. The west window is about as plain and uninspiring as it is possible to see! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The south aisle showing the reconstructed clerestory and comparatively ornate aisle windows. Right: The north aisle showing the original Norman clerestory and plain aisle windows. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Norman chancel arch. The south pier has been cut off during one of the nave rebuildings. The rood lost can clearly be seen and the decorative courses of the arch have been damaged at the top during the removal of the rood itself. Centre: The attractive hammerbeam roof. Right: The nearly-separated tower. The bottom course is transitional, showing pointed arches and blind arcading. The second and third stages are Early English very typical of towers in Lincolnshire and Rutland. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These “stiff leaf” foliate capitals date from the western extension of the nave in the late c12. Although still very typically Norman, they are more ornate than the capitals in the earliest part of the nave - see below. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: As scalloped capital from the eastern end of the nave. Right: The font is, according to the church guide, a Jacobean “copy” of a Norman font. I If it was indeed meant to be a copy then it is a poor one, It is, however quite elegant and it would surely be more just to say that this font was designed to be sympathetic with its surroundings rather than a copy of a Norman font? I don’t know where the original - presumably Norman - one is. Probably serving as a cow trough somewhere where most of them seem to be “discovered”! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Like most of its ilk, Whaplode’s wooden rood screen was removed at the Reformation. However, the “balcony” part - that which allowed access to the rood - remained until 1773 and this fragment is mounted on the wall of the north aisle. It is important to understand that the objection to rood screens after the Reformation was they were designed to separate clergy from congregation, the very essence of the of the difference between Roman Catholic and Protestant practice at that time. The survival of the balcony itself was not, therefore, any great surprise. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Another view of the chancel arch and, beyond it, the chancel itself. Rebuilt in the Victorian era, it is a rather mean affair, too small for such a large church and with its window half-obscured by the c18 reredos. Right: The tomb of Sir Anthony Irby (1st Earl of Boston) and his wife, Eliazabeth in the south west aisle. This being a staunchly Parliamentarian area. Sir Anthony was commander of a Roundhead regiment. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The three surviving roof angels. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The rather grim north aspect (with that dreadful roof!) that even the Norman clerestory struggles to redeem. Right: The Transitional stage of the tower, showing typically Norman decoration but with pointed Gothic blind arches. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The west end. The doorway is transitional, although with more of an Early English than a Norman feel to it. The west window is, let us say, “unfortunate”! Right: This view of the east end of the chancel roof reveals the roofline of the original Norman chancel. Above this is a very nice original Norman window peering out from the top of the nave, with two short string courses. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||