|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

became of him - he may even have died at Hastings - but he was supplanted by the Norman Robert of Tosny, Earl of Stafford who promptly gave the abbey to a Benedictine abbey at Conches in Normandy from whence the family came. The church he inherited was typical of its period with a central tower, short chancel, longer nave and with small porticus chapels either side of the tower. The village now became known as Waghanes Wotton. The Normans built a small priory and also enlarged the church with new nave, chancel, south aisle and transept, built around the central core of the tower. The c13 saw changes made in the Early English style. The south side porticus gave way to south transept and a south aisle were added. A small chapel was built at the south east of the church. In the c14 this chapel was extended almost as far east as the chancel itself, forming the Lady Chapel that was de rigeur at that time. The c15 saw the addition of the clerestory in Perpendicular style and incorporating a string course adorned with grotesque figures. One presumes that the heightening of the tower also occurred during this period. The inevitable Victorian restoration occurred in 1880 under George Gilbert Scott. There is a “messy” feel to this church. Architecturally, it is a real mongrel. Around that priceless Anglo-Saxon core there is a bit of everything and the various styles rub up against each other in bewildering profusion: it’s not an easy church to “read”. Not much mentioned in the “literature” is the profusion of rather idiosyncratic grotesques, both inside and out, which have suffered a fair bit of weather damage but which partly imbue this church with its slightly chaotic character. The south eastern chapel area is like some kind of Church attic where display boards and cases of artifacts are crowded in amongst monuments to the great and the good. It’s a welcoming place and the village is clearly proud of its church. It’s well worth a visit if only for that amazing crossing. It rather reminds me, though, of a home with lots of young children and a dad that likes d-i-y: very untidy, toys everywhere, and with lots of bits of building that were executed with more enthusiasm than good taste! |

|

|

|

Left: The south east with its large eastern chapel. Note the monument slabs on the outside of the church. Ugh! Right: From the north side the church looks, quite frankly, a bit grotty! Note there is no north aisle, so the clerestory is just an extension of the north wall and it doesn’t look “right”. The topmost section of the tower is different stone from the rest. The chancel is disfigured by massive buttresses. This picture, however, is revealing. Look at the slope of the ground from west to east. The Anglo-Saxon church extended a little to the left of the tower but the extended chancel of the present church uses ground that no sane builder would regard as ideal. The result? Ugly buttresses everywhere. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: My apologies for the distorted perspectives of this picture of the north east of the church caused by an ultra wide angle lens. Even the west end needed a buttress, and it’s a real monster. Note the odd look of the clerestory on this aisless side. Right: The south west. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Sandwiched between two the innumerable buttresses on the north side is this Anglo-Saxon doorway that once led from the tower to a porticus. You might well be wondering what is the difference between a “porticus” and a “transept” so I discuss this in the footnote to this page. Centre: This small blocked doorway is at the west end of the church. Nobody is sure whether it is Anglo-Saxon or Norman. I am inclined to thinking it is Anglo-Saxon. During that period there would frequently be a “narthex” - a kind of early porch - in front of the main doorway and west doorways were much more common in Anglo-Saxon than in Norman churches. Look too at those huge stones surrounding the doorway - again, more likely to be Anglo-Saxon, in my view. But nobody knows. Right: The south wall has a number of these vertical pilaster strips and they are adorned with badly weathered carvings such as these. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The north door. It is c15 and to its left is the original Norman doorway. Right: The west wall with its Perpendicular period window. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Right: The fine label stops either side of the west window are reputed to be King Edward III (1312-1377) and Queen Phillipa. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A study in Anglo-Saxon doorways. Of course, a crossing with four doorways means eight different perspectives. There are six here, a bit OTT perhaps but a perfect series of shots for illustrating the archetypical doorway of the period. The arches are supported on courses of what on an external wall would be called “long-and-short work”: alternating vertical and horizontal stones that are quite irregular and asymmetrical. The voussoirs (that is the individual stones that make up the arches) are also irregular, some quite neat others seemingly employing any old lumps of stone that came to hand! Look how small some of those keystones are! In between the arches and their supporting stonework are impost blocks of various sizes and geometry. The overall effect is of crude simplicity, but it is worth remembering that these doorways have survived the structural stresses and strains of 1000 years and more. The pictures show: Top Left: the south doorway from the south chapel and looking through to its northern counterpart. Top Centre: The south doorway looking from the crossing into the south eastern chapel. Top Right: The west doorway looking into the chancel. Lower Left: The eastern doorway from within the crossing. Lower Centre: The eastern doorway from the chancel. Lower Right: The blocked western doorway. The stained glass is of 1958 by Margaret Traherne and celebrates the legend of St Kenelm. He assumed the throne of Mercia in AD821 when only seven years old and was murdered under orders from his sister. His body was taken to Winchcombe Abbey in Gloucestershire where it was venerated (and generated income!) for centuries. Modern historians, however, say he was 25 when he died and that his sister was already in a nunnery! Well, the old monasteries never did let the truth get in the way of a good income! Mary Traherne’s work, by the way, can also be seen in Coventry Cathedral. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: This shot of the crossing has been taken with an ultra wide lens to capture three of the four doorways - and has captured something extraneous in the top left of the picture to boot! Obviously, the picture is distorted by the lens but it does show the extraordinary sight of three Anglo-Saxon doorways in one picture. The southern and northern doorways to what would have been portici (or chapels) are much the same in construction, but the eastern and western ones (see the earlier block of pictures) are rather different. Were the portici added in a later phase of building perhaps? Right: The eastern chapel seen from where the southern porticus of the Anglo-Saxon church woukd have stood. Few churches “do” clutter with quite the unbridled enthusiasm of Wootton Wawen church but then few churches offer so much information about the history of both church and village. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The eastern chapel looking through its arcade into the western end of the chancel beyond. Right: The eastern chapel looking towards the east. |

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

Left: The eastern chapel has this canopied tomb of Francis Smith (1522-1605). He was Lord of the adjoining Wootton Manor and a staunch Roman Catholic at a time when this could be a lifespan-threatening preoccupation! Like many of his co-religionists, he managed to duck and dive his way through the dangers of the Reformation to the extent that, as the Church Guide wryly observes, he now monopolises the squint from the eastern chapel through to the high altar. The poor man is paying for his hubris with the most uncomfortable posture imaginable! Centre: This monument is in the chancel itself is of John Harewell (1365-1428). The dog under his feet, by the way, tells us that John died a natural death and not in battle. Right: The chancel looking west towards the crossing. The chancel here has a detached feel to it, enhanced in no small way by the blind that blocks the glazed door through to the crossing. The cruciform plan with central tower and crossing was ideal for the ancient liturgy where separation of clergy from the common herd was de rigeur but must be a thundering nuisance in our post-Reformation churches. The crossing sits there as great big obstacle between nave and chancel and, in the case of Wootton Wawen, the answer has been to have altars in both the crossing and the chancel. What with the rather grim blue carpet, this chancel, like the eastern chapel, is - to use estate agent-speak, in need of some updating and modernisation! |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Left: The arms surmounting Francis Smith’s tomb. Right: The font is at the west end of the church. It is a plain octagonal piece from c14. The Church Guide surmises that the supporting eight heads are of monks and suggests that the same sculptor worked at Snitterfield and Lapworth churches nearby. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

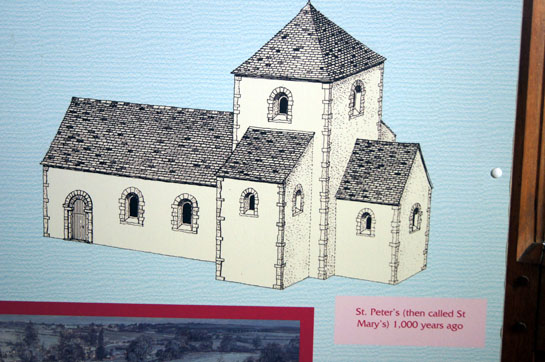

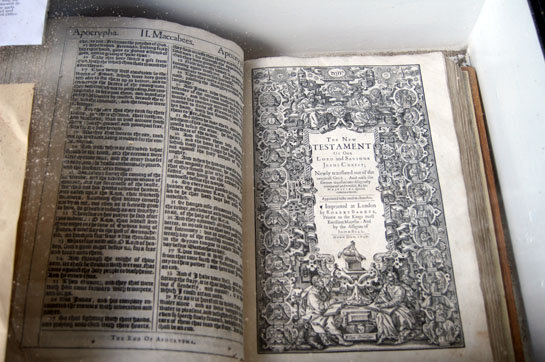

Left: The church’s display boards show this very useful artist’s impression of what the original Anglo-Saxon church looked like. Right: The numerous display cases include this 1697 “Black Letter” (that is, Gothic script) Bible. |

|

|

|

Left: One of the Norman nave windows. Right: Little remarked upon is the gallery of rather bizarre carved figures which adorn this church both inside and out. These date from the c15. This one has a most peculiar face and a bat-like wing. No doubt some “explanationist” will be able to furnish me with a fanciful notion of what this figure represents but please don’t waste your time. |

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

A couple more grotesque inhabitants of the nave. |

|||||||

|

|

||||||

|

A couple of the external grotesques. These were rather large and very distinctive in style but they have suffered grievously from weathering. |

|

Footnote - Porticuses and Transepts |

|

I have used the word “Porticus” freely in this page and on several others that refer to Anglo-Saxon churches. If Wootton Wawen Church had porticuses (and, no, it’s not “portici”!)”either side of its central tower you might reasonably ask why similar structures either side of a gothic church crossing are instead called “transepts”! Several architectural glossaries manage to avoid the issue. The answer seems to be, however, that transepts are used mainly to increase the space within a church whereas porticuses had their own defined functions, usually as small chapels. This is a bit confusing because, as we know, altars are often placed within transepts but, nevertheless, the space is generally available as an extension to the body of the church for use in its everyday functions. A porticus, on the other hand, would almost be a separate annex to the church and would be accessed, as we see here at Wooton Wawen, by a doorway rather than being open to the crossing. Indeed, it is believed that at some churches, notably Brixworth in Northamptonshire, access to porticuses was only from outside the church. Burial within a church was actually forbidden by the Council of Nantes in AD658 and reiterated by the Council of Aachen in AD809. The use of a porticus, or even a series of them to form an atrium, got round this rule and must have proved useful for those anxious to inter Saints, Kings and Bishops within the church precincts. |

|||

|

|

|||