|

Alphabetical List |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

County List and Topics |

|

|

|

Please sign my Guestbook and leave feedback |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

carving was by her own gardener – and you will see how remarkable this is. The outside of the church is unremarkable neo-Romanesque two-celled church with an apse. There is a fair number of such Victorian fancies to be seen around the country. The west end, however, tells you that this church is something special and prepares you for the wonders within. If you are not aware of the date of this church you will probably immediately think “Arts & Crafts Movement”. Sarah Losh’s vision, however, pre-dated that movement by decades. The focus on traditional craftsmanship, the use of traditional materials and the rejection of anything that was not aesthetically beautiful, however, is all typical of that movement. Quite simply, Sarah Losh “got there first”; before William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and the rest. She did not as far as we know overlay her artistic passions with the rather na´ve and patronising social ideals of many in that movement. Hers was, it seems, a personal artistic statement and nothing more. You can see Arts & Crafts churches on this website at Brockhampton and Roker. Most such churches can list item by item those responsible for their design and manufacture: roll calls of the great and good in mid to later nineteenth century functional art. Wreay has no such pretensions. There are no famous artists, no renowned carpenters, no vaunted glaziers to be enumerated here. This is one person’s vision. You may feel, as I do, that St Mary’s Wreay outdoes them all. “Avant Garde” doesn’t begin to describe it. It is astoundingly ahead of its time. If I told you that it was contemporary with Sir Basil Spense’s Coventry Cathedral I swear you wouldn’t be shocked. What a remarkable place. The church with delicious understatement expresses its pride in being one of Simon Jenkins’s “Thousand Best Churches”. In my view it is one of the ten best. Simon, incidentally, is its patron. There are further treats outside the church. The Losh family graves are enclosed by a low stone wall. Both Sarah’s and Catherine’s graves can be seen here and their stones are adorned with carving very much in the flamboyant style of some of the carvings within the church. There is a mausoleum that is a memorial to Katharine. It is strangely plain and severe compared with its lavish neighbours. Within is a statue of Katherine seated and holding a pine cone, of which more anon. Next to the mausoleum is a full sized copy of the famous Bewcastle Cross. As Simon Jenkins notes, it is invaluable since the Anglo-Saxon original (still in situ and very much worth a visit) has been weathered over the centuries. The pine cone motif is a recurring one within the church. It refers to a family friend, Major William Thain, who served at Waterloo and who was killed in the Afghan Wars in 1842 the year in which the church was consecrated. It is said that he sent a pine cone to Sarah before he died. |

|

|

||||||||

|

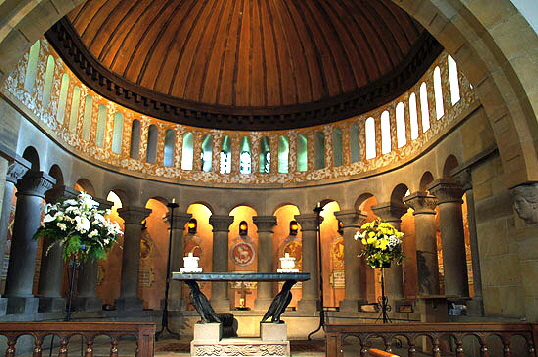

Left: Looking towards the apsidal east end. Note the plethora of wood carvings. Right: The apse. It is more Romanesque than most “real” Norman architecture in this country. There are thirteen niches, one each for the apostles and with their names and symbols on the wall behind, and one for Christ denoted by an Agnus Dei. It is not too difficult to imagine this apse set in Rome for use by Magistrates, for example - because, of course, the Romans used the basilican design for secular as well as for religious buildings. The row of windows above is, however, very much an idiosyncrasy of this church. |

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Left: Niches within the apse. The soft lights within seem too have been designed to give an oil lamp-like glow. Right: Some of windows above the niches. They have stencil-like inserts |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The altar table. Its design and placement enhances the impression of a dining room. Right: The lovely wooden roof over the apse. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Looking towards the west end. Note the line of stained glass windows that follow the roof line. This is particularly attractive - and particularly had to photograph because of the angles and intervention of the roof beams. Right: There is a kind of clerestory at the top of the nave, the windows in sets of three and with stained glass. The designs are mainly comprised of a patchwork of mediaeval fragments purchased by William Losh from the Archbishop’s Palace at Sens in France. The outer windows in each set have large contemporary floral motifs set within the mediaeval glass. The central window in each set, however, has a darkened background, so that the motif alone allows the light through. It is a very composition. All of these windows sets are extraordinarily avant garde for a time when the Victorian factories were churning out acres of mediocre biblical windows. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Two more clerestory window sets. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

When you look at these wonderful wood carvings you have tor remember that they were done my Miss Losh’s gardener! Left: The lectern is a traditional eagle in a fra from traditional style. Why an eagle? Nobody really knows but there are many theories. Some associate it with St John the Evangelist, who is traditionally represented in the shape of an eagle. Others say it is because the eagle flew closest to heaven. The eagle was also featured in mediaeval bestiaries and you can see its significance in my entry for Widecombe. Centre: The pulpit is made from a stump of ancient bog oak. The offshoot to its right holds a candle. One of the (myriad!) Church Guides suggests that this represents Christ bringing light to the world. I note also that its trunk appears to be a palm which also has significance in early Christian iconography. Right: My favourite piece is this splendid Pelican. Its significance in Christian iconography is described in many places on this site. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: An owl and a cockerel. adorn this wall-mounted plant stand on the north wall to the left of the chancel arch. The Church Guide suggests that they represent day and night made by God at the Creation. Centre: A unidentifiable archangel carving next to the chancel arch. Right: This archangel is recognisable as St Michael - he has a dragon below his feet. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Above the chancel arch is this representation of Heaven - seven angels interspersed by palm trees |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Four Images of the font. It is thought to have been carved by Sarah Losh herself and reveals her as a considerable craftswoman as well as a rich imagination and keen eye for symbolism. These are all surely symbols of the new life that is promised by baptism. Top Left: We can see here a dove with an olive leaf in its beak; a scene from the story of Noah. On the right you can just see a bunch of grapes. Top Right: Various plants are shown on this side. The central motif is meant, I think, to be a water lily. Bottom Left: We can see here ears of wheat or barley. On the right is a dragonfly. Bottom Right: A butterfly. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Two of the nave windows, again showing re-use fo mediaeval glass. Right: The west door from the inside. Note the handles are of a pine cone design. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

More pine cones. Left: On one of the capitals in the apse. Right: One of a pair of cones just inside the doorway before the westernmost pews. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The lovely west doorway. It has the proportions and some of the features of a late Norman door but it is unmistakably modern. Note the huge pine cone labels stops. Apart from remembering Major Thain’s last gift to Sarah Losh, the pince cone is an emblem of another life to come. Right: The iron arrows on the outside of the door are particularly iconic and surely unique? The pine cones symbolise life but the arrows symbolise death and it was an arrow that killed Major Thain. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The three west windows are complementary to the west door. Left: This window has several exquisitely-drawn butterflies (I’m assuming they are not moths!) and more wheat or barley plants. Centre: Pine cones are much in evidence here. There is a lovely barn owl on the right - I really do think that the carving is so good that you can identify the species. the bird oppositethe owl is not so identifiable! Further up we can see a beetle on the left with an indeterminate insect opposite. It could even be a fly, but I don’t suppose it is! Right: There are more pine cones here. We can also see sea shells on either side near the bottom. There are stylised flowers complete with elaborate stems near the top. Mediaeval masons would have envied the ability to carve so beautifully. They did not have the same quality of tools of course and very few of them would have been professional carvers: they would have been masons filling in with a bit of decorative work, not the other way round. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Now we come to the fun. Most of what is inside is beautiful but deadly serious. These grotesques, on the other hand, are banal in the extreme. The tortoise is easy enough to identify but the other two figures are just fantastic figures. I believe that we can, surprisingly, draw some serious conclusions from these and other features of this comparatively modern church - see my footnote below. These are the only grotesque carvings at this church and all are on the north side. Could Sarah Losh have consciously been portraying the north as “The Devil’s Side” as it was characterised in mediaeval England? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The single bellcote is topped by another eagle. Right: The arrow motif re-appears charmingly as a set of railings around the “well” near the west door. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: The Losh burial plot north west of the church. Note the pine cone! Right: The mausoleum. We found this curiously stark compared with the visual delights elsewhere on the site. To the right is a reproduction of the Anglo-Saxon Bewcastle Cross. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Sarah shared a grave with her sister, Katherine decorated with scallop shells and palm fronds. Right: The grave of Sarah’s Aunt Margaret - with pine cone! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left and Centre: Elements of the Bewcastle Cross. It is thought that this might be a monument to Katherine. Interestingly, however, and it is purely a personal view that nobody else has suggested as far as I know, I can’t help feeling that its style perhaps influenced the style Sarah created for the church. Right: The apse. I do not know the significance of the crypt-level north door. Note the windows above the blind arcade. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The painting of Sarah Losh that hangs in the church. Beauty, brains, creativity and money. Yet she remained unmarried. I am sure she was not short of offers! |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Footnote - What can we Learn from Wreay Church? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I think Sarah Losh’s vision here was quite remarkable and perhaps shows that the Arts & Crafts Movement were not as avant garde as they liked to believe! More than that, however, I am intrigued about what insights Wreay Church might give us into the ways in which her predecessors in mediaeval times might have thought and worked. By dint of the derelict state of the church and her financing its rebuilding, Sarah was obviously given a free hand in the reconstruction. It would be easy to forget that she did not own the church and its land. I spent a lot of time studying the work of the masons in the East Midlands; work that resulted in my book “Demon Carvers and Mooning Men”. During that period I found that remarkably little is known of the modus operandi of the masons who created our parish churches. For much of the twentieth century there was a widespread assumption that our parish churches were in some way “commissioned” by the clergy or even by the “Local Bishop”. The reality was very different. Most of our stone parish churches would have started life under the patronage of the local Norman grandee parachuted in by William after the Conquest.. Others would have been commissioned by monasteries and priories and maintained by them with varying degrees of enthusiasm until the Reformation. In many cases, the local nobility and minor gentry would have continued to endow the local church, not least in order to gain a degree of remission from the dreaded Purgatory. It cannot be over-emphasised, however, that the prime movers in church building, and particularly in the expansion of churches in the High Gothic period, were the layity and not the clergy. It is now well-established from the scant written evidence we have that the Master Mason had extraordinary discretion in church construction. Yes, we know that patrons - who were sometimes just the worthies of the parish - would have suggested or approved the broad outline of work. We have evidence that patrons often specified that their church should be similar to one down the road - only theirs should be bigger and better! We also know, however, that none would have been in any position to challenge the Master Mason about what was possible and what was not. There is no evidence that the parishes were in any position to call for tenders from masons and we might even suppose that the Masons Guilds would make darned sure that no such competition could take place. The mediaeval world was not shocked by monopolies and cartels as we are today. Nor we should suppose that the appointed Master would have been submitting detailed plans for approval by some sort of Committee such as we would take for granted today. In my book I debunk the idea that the decoration of a church - in particular external friezes and gargoyles - has some religious or spiritual significance had we the eyes to see it. Oh, those spiritual Mooning Men eh?! Sarah Losh’s Church is her vision. Five hundred years after masons were carving whatever they fancied on the outsides of churches in Northern Oxfordshire and the East Midlands and all over England, there is no suggestion that Sarah Losh had to consult anyone about the detail of her decorative scheme either. Much of what we see on the inside of the church, to be sure, is overtly or subtly religious but try looking for butterflies and owls in most parish churches if you want to waste a year or two of your life. In modern parlance, Sarah “did her own thing”. Indeed, when we look at the work she commissioned we might surmise that Sarah’s real love was that of the natural world in which she saw the work of God. What do we see on the outside of the church? The most grotesque - and amusing - of gargoyles. Iron arrows; sea shells; owls; insects. Just as with mediaeval carving, you can find religious “explanations” if it pleases you. Yet, what I see here is that Sarah Losh decided that the outside of the church was her canvas. This is where, as much as any Christian Victorian lady could, Sarah had a bit of fun. Just like her mediaeval predecessors, in fact.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||