|

|

Alphabetical List

|

|

|

County List and Topics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Most of you will have heard about the Solway Firth. Maybe a quarter of you might be able to place it on a map – it is on the west coast and separates Cumbria from southern Scotland. I’m betting that barely one in twenty of you will have visited the area on its southern banks. I went there mainly to see the Norman font at the church of Bowness-on-Solway. I had an itinerary worked out but a splendid locally-produced leaflet pointed me at some other worthwhile churches I might otherwise have missed.

Remote and little-known this area might be, but history seeps from every stone of its churches. Hadrian’s Wall ran along its length and stones from its forts – some inscribed by legionaries - are visible in the walls of many of the churches and other buildings. The wall was there, of course, to keep out the marauding Picts. In the second millennium the new nation of Scotland became England’s fractious neighbours - and we theirs!.

When the kings of the two countries were not invading each others dominions, the locals on both sides of the Firth were raiding each others’ settlements, rustling livestock and generally making thorough nuisances of themselves. They are known to history as “Border Reivers” from the Old English word “reive” - to rob. Sometimes they were egged on by their respective kings, rather in the manner of Tudor pirates. Don’t, though, make the mistake of thinking of the reivers as patriots. They were thieves, often bound by extended family ties, and were certainly not above carrying out raids on their own sides of the border. The legacy of this strife can be seen all over Cumbria and other parts of the border – ”pele towers” designed to protect the local populace against raiders. Reiving weas not confined to the Solway, of course. It was prevalent all over the border region. Corbridge in Northumbia even has a surviving pele tower that was specifically to protect the vicar! As we will see, Newton Arlosh Church had a fortified west tower for precisely the same purpose. King Edward I – “The Hammer of the Scots” died of dysentery in the marshes of Solway near Burgh-by-Sands on his way to yet another invasion.

The Anglo-Saxons were here too, of course. This is a land where many of the early Christian saints walked – especially those Celtic monks who had made their way across the Irish Sea to bring Christianity to the pagan population. The Vikings were here too, many from the Viking Kingdom of Dubhlin (yes – that Dublin!). Although they were not exactly pacifists they were perhaps more intent on settling and farming than in the rape and pillage that characterised their earlier incursions on the east coast.

All in all, then, this quiet and area sparsely populated area was a melting pot. None of the churches I describe is a wonder in itself, but most have something of interest and the distances are very short. A saunter through this itinerary is rewarding and gives a superb insight into a part of our island history that is not well known - and a look at an area that few of your neighbours will have visited!

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you are going almost anywhere in this area you are likely to be following the B5307 west of Carlisle. We were en route to Bowness-on-Solway but Burgh-by-Sands church is right next to the road so we stopped - and we were glad we did. It started life in the twelfth century as a simple Norman church and was built on the site of the Roman fort of Aballava on Hadrian’s Wall. Stone from the fort was used for all phases of this church. The nave, the western end of the chancel and the north doorway all date from this period. The north aisle, however, is of the thirteenth century - the Early English period - so the Norman north door must have been moved here from the original Norman north wall. It has some beakhead decoration still in-situ. There was also a south aisle but this has long disappeared.

The west tower is fourteenth century. Burgh was close to fords over the Solway Firth and so this tower was built very much as a defensive work. Too many English church towers are proclaimed as being for this purpose with little to support the theory, but Burgh undoubtedly fits the bill. Its walls are two metres thick. It has no external door and the windows are tiny. The west door inside is very small and is protected by an iron “yett” or gate. If an assailant got beyond the south door – with missiles raining down on him from the tower - he would

|

|

|

|

|

probably be jostled by the village’s lifestock which would have been herded into the nave for safety. He would then have to break through the west gate and the strongly fortified door. Being so narrow, the doorway could be held by a single defender, man to man.

If he managed to fight his way past the door he would find himself in a tunnel vaulted room. To reach the people sheltering in the upper floors he would now have to force his way up the spiral staircase, fighting every inch of the way against defenders who would have a height advantage and who would be desperate to protecting their families. If the raider killed one man, then he would have to get past the corpse while the next defender was hacking away at him! The tower wouldn’t have stopped a besieging army but bands of raiders would have found it a very tough nut to crack.

Bizarrely, a second tower was later added at the east end. This was probably meant to house the priest and its only entrance was from a small door beside the altar. The upper portion has been demolished but its base still remains. This then, is a church without an east window.

King Edward I died of dysentery at Burgh on 7 July 1306. His body lay in this church for several days, an extraordinary chapter in the life of a small parish church. Nearby you can see a signpost to a monument on the marshes, said to be on the every spot that he died. The monument is dire, to be honest, but you might like the marshland walk. Much better is the statue of the king in the village and little down the road from the church.

|

|

|

|

Left: The view towards the east end. Note the absence of an east window caused by the erection of an east tower. Right: The view to the west end.

|

|

|

|

Left: The gate - the “yett” - through to the fortified west tower. Centre: The north door with some original plain beakhead moulding. Right: King Edward I

|

|

|

|

Left: The unusual east end that is now residential accommodation. It was originally an eastern tower, probably designed to house the vicar. Right: A surviving Norman corbel mounted on a wall.

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you are new to this area – as we were – you will enjoy the last few miles to Bowness. The sandy estuary is visible for some distance with the Scottish south coast clearly visible. Signs warn you of the alarming amount of water than can cover the road when there are bad combinations of weather and tide. A lot of the road is part of the Hadrians Wall long distance footpath. Bowness itself is at one end of the route. It feels like the end of the world on a cold windy day!

Sheltered by a small headland, Bowness was the site of the Roman fort “Maia” which was the second largest on Hadrian’s Wall. Bowness would have been a first port of call in the first millennium for many ships crossing from Ireland and it is likely that many of the Celtic missionaries passed this way before heading inland to the Kingdom of Northumbria. Similarly, Bowness was a relatively safe crossing point of the Firth. The Church Guide is able to speculate that many of the great early “British” saints may have passed this way.

The church, in truth, is of scant architectural interest. The north and south doorways are late Norman but without decoration. There is a Norman window in the chancel. It is a church that has been heavily restored but there are still Roman stones visible on the exterior.

|

|

|

|

|

The treasure here is the Norman font. Its stylised decoration is quite elaborate. It is also, however, an unusually well-crafted piece. Most Norman fonts are either square or circular. Bowness’s font however uses sophisticated chamfering to make a font that is octagonal at its base become square at its lip. Of course, as they invariably do, this Norman font has a history of being unloved. It was consigned to the churchyard before doing service as a flowerpot in a local garden before being restored to its rightful place in 1848.

|

|

|

|

Left: This windows appears to have a bit of Norman string course recycled into its sill. Centre: The late Norman north doorway. It has decorated capitals that have been badly damaged. Right: The Victorians really went to town in Cumbria; and Bowness-on-Solway was not alone in being mercilessly duffed up. The Victorians rescued many a church from total dereliction so one shouldn’t be too hard on them. Mind you, whoever had the bright idea of framing the faux mediaeval windows here with red sandstone surrounds and even even sandstone blocks around the chancel windows, should have been politely told to go and do something anatomically impossible. The shape of the church is fairly typical of the area: western bellcote and a straight uninterrupted roofline from west to east. What with its enormous - but I am sure necessary - buttresses, if poor old Bowness Church had been a horse it might have been a kindness to shoot it. It is though a perfectly nice church on the inside and of course that’s what matters to a congregation, which is fair enough.

|

|

|

|

The treasure here is the Norman font. Its stylised decoration is quite elaborate. It is also, however, an unusually well-crafted piece. Most Norman fonts are either square or circular. Bowness’s font however uses sophisticated chamfering to make a font that is octagonal at its base become square at its lip. Of course, as they invariably do, this Norman font has a history of being unloved. It was consigned to the churchyard before doing service as a flowerpot in a local garden before being restored to its rightful place in 1848.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although heavily restored in the late nineteenth century, Kirkbride has fared rather better than Bowness. Its proportions are pleasing and it retains its original chancel arch which dominates this tiny structure.

As with Burgh-by-Sands, this church is built on the site of a Roman fort. It was of wood, not stone. It stood at the western end of “Stanegate”, a Roman road built by Trajan in AD105. Another road linked Kirkbride to Bowness-on-Solway which was the site of the second largest fort on Hadrian’s Wall. Once the wall was built it is likely that the fort here was abandoned. Many artifacts have been found here, including a pagan altar.

Pevsner has the church as “essentially Norman” but some other authorities seem to believe it was originally Anglo-Saxon. It is a tough call and much depends whether you think the chancel arch is Saxon or Norman. It has the simplicity of the former, but the regular masonry of the latter. Really, there is no evidence for Anglo-Saxon although there might well have been an Anglo-Saxon church on this site originally.

The chancel has blocked niches on either side, making this a very interesting

|

|

|

|

|

architectural composition. There are three doors, all Norman and quite plain.. The blocked northern has a massive lintel. There are two surviving Norman windows, one each in the north walls of the nave and chancel. There is supposed to be a Norman holy water stoup here but somehow I managed to miss it which is very embarrassing. The Perpendicular style font is a quite attractive piece with a floral design around the bottom of the bowl and a quatrefoil design above.

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking towards the east end through the beautifully-proportioned Norman chancel arch. Note the niches either side of it. Right: The chancel. The window on the north side is Norman, as is the south door. The east window dates, of course, from the Victorian restoration.

|

|

|

|

Left: Looking through the chancel arch to the windowless west end. Right: An original Norman window on the north wall of the nave flanked by two Victorian windows, of which the least said the better....

|

|

|

|

Left: The perpendicular style font. Right: The church from the south east.

|

|

|

|

|

|

We have another connection with Edward I here. Nearby Skinburness (or “Grune”) was a port much used by Edward his forays into Scotland. The town was granted “Free Borough” status. The Bishop of Carlisle then granted a charter to the monastic house of nearby Holme Cultram (of which more later) to build a church. The port was, however, swept away by storms that breached the sea defences before the church could be built. The survivors built a new settlement inland – Newton Arlosh or “New Town on the March”. King and Bishop transferred the charters and privileges of Skinburness to this new place. It was probably started in around 1303.

Of all the towers in England, none has such an unimpeachable claim to having been built primarily for defensive purposes. It is to all intents and purposes a pele tower. The defensive arrangements were similar to those at Burgh-by-Sands. This tower, however, also has a small turret as well as arrow slits. The nave is similar: huge walls and tiny windows.

The church fell into total disrepair until Sarah Losh – famous for her rebuilding of Wreay Church – decided it must be restored. Her forebears were the “Arlosh” family. She commissioned a large parallel nave to the north and a tiny apse to

|

|

|

|

|

the east. If you visit my page for Wreay Church (better still, if you visit the church itself) you will see the same love Sarah had for Italianate Romanesque. In 1894 a man called George Dale Oliver decided to put the altar at the north side of the church (yes, really!) and make the apse into a vestry. The interior of this north-facing nave is quite odd: as plain as a non-conformist church and with walls that look like they have been decorated with Dulux paint and wallpaper! Thus the church presents a unique and most peculiar juxtaposition of fortified church with an interior of almost domestic appearance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The north-facing altar. To the right is the entrance to the apse, now used as a vestry. To my eyes this is a grimly utilitarian interior. How was it possible to make it more so than its fortified exterior? Honestly, if this were a house for sale the estate agents would add the words “needs updating” because at the moment it looks neither historic nor modern. That’s to take nothing, of course, from Sarah Losh’s generosity in saving the place. She would be turning in her grave at what the 1894 changes “achieved”, one suspects. Right: The church from the west - yes, I know it’s confusing. The nave and chancel are now, remember, facing the north! The rounded doorway you can see -- and which again demonstrates Sarah’s love of the Romanesque - is a west door and as you entered “her” church you would have had the eastern apse facing you. Although Pevsner in particular is scathing about the later re-orientation of the altar you can see why, from a practical viewpoint, it was necessary. Sarah Losh’s configuration would have had a tiny distance between west door and the tiny apse with a large empty space to its right. It is a very difficult structure to understand..

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The east end with Sarah Losh’s apse - now a vestry! Centre: The rather awful south end of the church. Right: This rams head corbel was carved by Sarah Losh herself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Far Left: This eagle on the east gable is also Sarah Losh’s work. She also carved one on “her” church at Wreay. Second Left: The west door has an elegant simplicity that only serves to highlight the architectural confusion of much of the rest! Second Right: The font is the oldest thing in the church. It is probably thirteenth century and probably from Holm Cultram Abbey - which we will be looking at next. The other faces are plain. Far Right: This picture shows the depth of the walls in the tower. You can also see that it was useful for the storage of mediaeval vases, jam jars and whatnot.

|

|

|

|

|

|

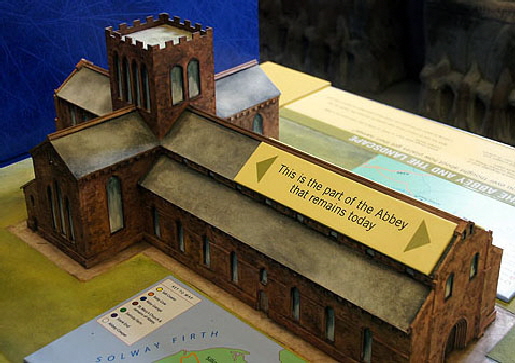

You will find this church in the appropriately-named Abbeytown. Of course the abbey was dissolved with all the others in Henry VIII’s reign but some of its church survives for use by the parish. It was a Cistercian house founded in 1150 by the monks of the famous Melrose Abbey and built from red sandstone from the Scottish side of the border. At that time Holme and the rest of this area was held by Scotland but in 1157 it was gained by Henry I of England. The abbey covered ten acres. Like most of the churches in the area,it was for centuries embroiled in the cross-border shenanigans. It was raided in by the Scots in 1216. Edward I stayed here twice en route to invading Scotland. Robert the Bruce devastated the abbey in 1319 despite his father being buried within its walls. The pattern of raids and short-lived truces went on for centuries until Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell wrought their own havoc. Cromwell, however, allowed the church to remain after the local people petitioned that it was their only defence against the Scots – which was still, let us remind ourselves, a separate and generally hostile kingdom. In 1557 Queen Mary gave the church to Oxford University.

A familiar story ensued. The church now served a parish that was in no position to maintain it. Lead and stone were stolen. Originally a cruciform church, the central

|

|

|

|

|

tower collapsed on New Years Day 1600, taking much of the chancel, and some of the nave and transepts with it. The University repaired it but the new chancel was promptly destroyed by a roof fire. In 1703 one Bishop Nicholson ordered its restoration and the nave was reduced in size to six bays and the aisles removed. Still neglected, it needed more work in 1833. Various restorations have been carried out throughout the twentieth century. Then, just to cap it all, there was an arson attack in 2006! So work is still being carried out. I think you might dub this place the Abbey of Misfortune.

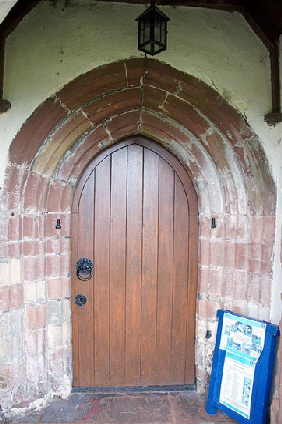

It is still worth a visit despite these depredations. The west portal is described with some degree of hyperbole as “glorious” by Pevsner. The mighty west doorway has a rounded arch but being late Norman it has little adornment. The nave bays with of two levels have pointed arches. The aisles have gone so these arches are now blank.

|

|

|

|

Left: In most churches the view to the east will be the best, but not in Holm Cultram because the original west end has survived whereas the east has not. The church was begun in the mid-twelfth century. The building, I surmise, must have taken many years because these filled in arcades with their multiple shafts and slightly pointed arches are distinctly Early English in appearance, not Norman. This is perfectly plausible as this was a vast building and it would have been started at the east end, not the west, and such an important foundation might well have been in a position to be “ahead of the game” architecturally adopting that new-fangled style from France! Right: The only word I can find to describe the east end is “abrupt”! Beyond the east window would have been the axial tower which has long since disappeared. There are plans, however, to restore some glory to this end of this long-suffering church.

|

|

|

|

Left: The west end. Of course it has lost the wings that would have fronted the demolished aisles but what is left presents a proudly defiant face to the world. This is the “Church that would not die”! What we are seeing here is the porch that was added in 1507 by Abbot Chambers. It is poignant to see the little bell cote that stands in lieu of the full peal of bells that would have been housed in the old tower. Centre Upper: The original west door gives some idea of the original magnificence of this church. It has five orders. You can see, again, that this is a Transitional rather than a Norman doorway. Centre Lower: Porch doorway capital. Right (both): Label stops on the porch doorway. In the lower picture you can see the initials of (Abbott) Robert Chambers above a chained bear.

|

|

|

|

Left: A cluster of arcade capitals inside the church. Right: The north side with its rather sad and incongruous factory-like windows.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aikton is one of those simple little churches that time has almost forgotten. It is in an attractive setting and, as is so often the case, its simplicity and unpretentiousness is quite beguiling, Little seems known of its history.

Structurally it is a simple two celled Norman church of the twelfth century. All of the windows were replaced in 1869 so all that is left to betray its origins is the simple chancel arch. The south aisle seems to have been added in the Early English period and the simple but rather pretty south door seems to confirm that. The aisle roof is a simple continuation of the nave roof, producing what we call a “catslide roof” - surely one of the most charming terms in English architecture? The aisle is low and narrow - one might reasonably wonder what use it was!. Many English churches would have had aisles like this once but the fifteenth century mania for aisle widening and clerestory building changed the profiles of many churches for ever. Not in this remote area of Cumbria, however!

There is a simple font that is generally thought to be Norman but which Pevsner puts at fourteenth century. The crudely carved bowl looks Norman but some of the designs look later. The exposed timber tie-beam roof completes the picture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The view east with the Norman chancel arch and exposed tie-beam roof. The aisle arcade is Early English. Right: The chunky font of disputed date. The quatrefoil-like and arched designs are reproduced on the other faces. There is a Moor-ish look to the “arches”. To me it looks very crude to be fourteenth century as Pevsner claimed, but who knows?

|

|

|

|

Far Left: The view to the west through the chancel arch. Second Left: The chancel arch looking east. Second Right: The simple but attractive Early English south door. Far Right: In the porch is this rather splendid thirteenth century grave slab with an image of a sword. It is traditionally “associated” with Hugh de Morville, one of the assassins of Thomas a Beckett. His daughter lived in the manor nearby. However, it is now known that this is too late a piece to plausibly be Hugh’s and, in event, Hugh was a common name in the de Morville family. Still, it is a fine thing.

|

|

|

|

Left: The outline of a blocked lintelled priest’s door on the south side of the chancel. A gravestone completes its obliteration! Centre: The implausibly small south aisle. Despite my jocular comments, it is interesting to think that in the thirteenth century such a tiny community still needed extras space for its devotions. Right: The church from the north west. You can see that the north wall is of different masonry from the rest of the church. Surprisingly, this altogether neater looking wall is the original Norman wall whereas the others were rebuilt in 1732. Was it refaced, I wonder?

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like all of these churches, Kirkbampton is twelfth century; in this case 1194. Of all the churches in this "saunter" it is probably the most interesting. It is entered via the north door which is Norman with zig zag moulding. There are faint traces of a tympanum, with the figure of an abbot or bishop in one corner but it’s not easy to spot with the naked eye. The south door and south east doors are also Norman. The Norman chancel arch is a nice piece with decorated capitals, including a face peering out on the north side. The Church Guide says that it is a Green Man but I could see no signs of leaves around his mouth or face. There is a very low so-called leper’s squint on the south side of the chancel. More interestingly, a Roman stone was placed next to it during the restoration work of 1871. It’s inscription means: “The Vexillation of the 6th Legion, the victorious, pious and faithful did this work”. A “vexillation” was a company of veterans. The stone, of course, originated from Hadrian’s Wall nearby.

Structurally, the church is little different from the Norman original. There was restoration in the late nineteenth century and this presumably is the date of the gormless faux-Perpendicular tracery windows. The east window of three Early English style lancets, however, has glass by Burne-Jones. The vestry and south porch date from this time, the latter sadly too late to save the tympanum from near total destruction by the weather.

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The east capital of the north door. Note the crudeness of the decoration which is typical of this church. Right: The view to the east end with the modest Norman chancel arch.

|

|

|

|

Left: Around the altar table is a fascinating set of Victorian floor tiles. They have the instantly recognisable “Agnus Dei” at their centre. The real curiosity, however are the dice motifs between the points of the eight-pointed stars. These represent the soldiers gambling for Christ’s clothing during the Crucifixion. Interestingly, most versions of the Bible say that the soldiers cast lots for the clothing, and only one or two refer to dice. You might feel as I do that this is an obscure and not particularly outstanding part of the Crucifixion story. Why choose it as a motif for floor tiles? In a thousand years time will observers understand the allusion at all? Much “interpretation” is carried out on mediaeval church art to ascertain “what it means” and we are earnestly told that it was to educate the poor benighted peasants who could not read. Did this Victorian church tile have an educational value? Of course not. Someone had a good time designing it and coming up with something that pleased him. Why do we think that mediaeval masons and craftsmen did not just please themselves? Discuss in no more than 1000 words....! Right: The low side window from within the chancel. The Church Guide goes down the usual path of “Leper Window” or “Leper Dole Window”. Personally, I think it is absolute bunkum because lepers were generally excluded from normal society altogether. More damning is the fact that the goings on of the priest within the sanctuary of the chancel was normally hidden from the rest of the congregation. Would lepers have had a facility that others did not? And look how low this opening is! I had to move a wooden bench in order to photograph it. To the left of the “Unidentified Wall Opening” is the Roman tablet with its inscription.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The church from the south west. The triple lancet window installed during the restoration works well on this church and many Cumbrian churches have the “real thing”. Right: The south wall of the chancel . You can clearly see the blocked Norman north door and to its right one of two surviving Norman windows

|

|

|

|

|

|